Darcy Jeffs and Kevin Wolpoff live in Florence on Oregon’s coast, where Darcy can be at home for their son, Miles. But Miles, 6, is autistic and needs services harder to get in a pandemic.

Before COVID-19 arrived, the parents sent Miles to The Child Center, a non-profit in Eugene, for highly specialized therapy six hours a day, five days a week. The pandemic reduced that comprehensive schedule to six hours of distance teletherapy per week. Jeffs received training to help fill the gaps with home strategies. Still, she says, “Without in-person access to his prescribed schedule, we were experiencing setbacks.”

Now the couple, like most parents, is weighing what to do this fall. They hoped to send Miles to kindergarten with a Child Center therapist, but the public school districts in their area will not allow that. Besides, most plan only distance learning. Miles will return to The Child Center late August, and one private school that plans to physically open might have room for him and his therapist. But these options risk exposing him to the virus.

“There are no easy decisions,” says Jeffs. “We face a health risk on either side. Do we risk exposure or losing access to a very necessary therapy for our son?”

After schools shut down in Drain, a small town near Yoncalla, Jessilyn and Nathan Whiteman received no special education services for their son, Christopher, who has autism spectrum disorder. A private speech therapist in Eugene provided Christopher some service on Zoom. The Whitemans hope Christopher can attend kindergarten in person this fall.

“Christopher is already behind,” says Whiteman, “and we are doing what we can at home. But he needs help from a special education teacher. When his academics are behind it also affects him socially and emotionally.”

Losing ground

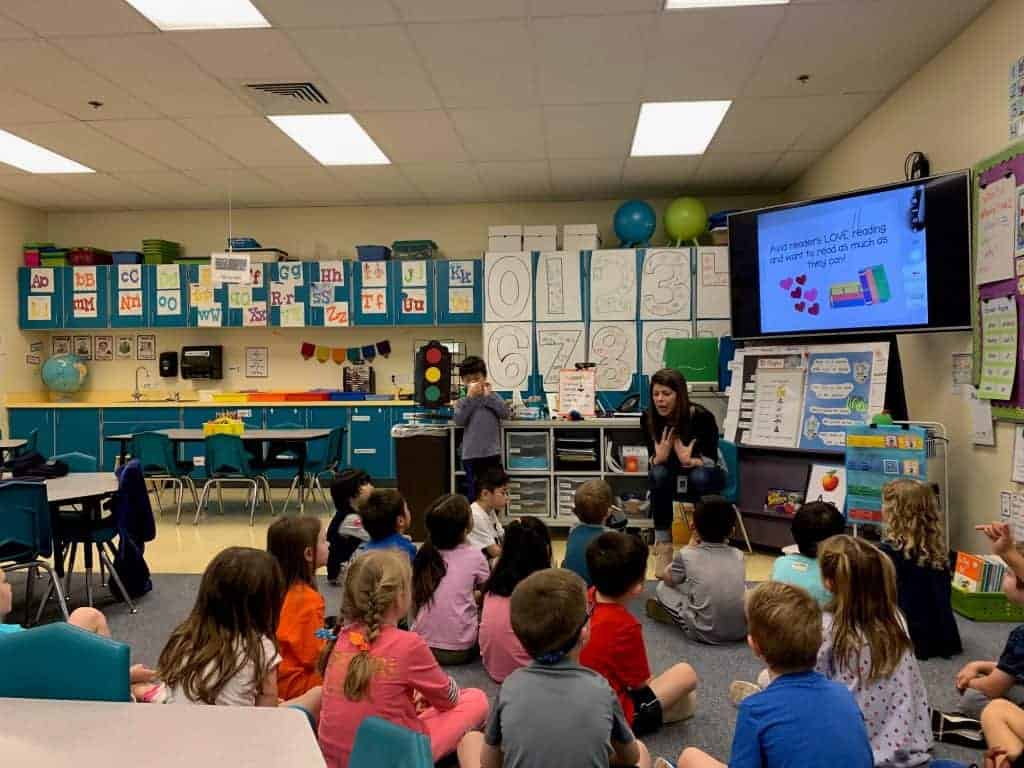

Ericka Guynes, principal at Earl Boyles Elementary in Southeast Portland, is concerned her youngest students already have lost ground after the spring closure.

“It is possible they may have lost a year of learning,” Guynes says.

Earl Boyles offers half-day public preschool classes that enroll a total 102 children and, along with Yoncalla Elementary, is a partner in the Children’s Institute’s Early Works program.

Another inequity is inherent in Oregon’s patchwork of early education programs, which have never been open to all children. The state’s public preschool programs and the federal Head Start programs serve less than two thirds of the low-income children who qualify. And private programs have become increasingly out of reach for low- and middle-income families. The state provides child care subsidies for only 15 percent of the low-income families that qualify. Parents pay for 72 percent of all funding for early care and education and thousands of them have lost their jobs because of the pandemic.

COVID-19 has “exposed a fundamental and underlying challenge of the financial mechanism for supporting early childhood education,” says David Mandell, policy and research director for the Oregon Early Learning Division.

So even if Oregon’s preschools are able to open this fall, they will open only for a fraction of the state’s 3- and 4-year-olds. And if those students are taught remotely, the quality of their education will be lower, says Barnett, with learning losses “much deeper in things like language, math and social/emotional development.” This deficit could have negative effects on children through life, he says.

Early education has a “profound impact on children’s development and their acquisition of social-emotional, language and cognitive skills, all of which are critical to their school and life success,” says an Early Learning Division report to the Oregon Legislature last December.