Children’s Institute Annual Fundraiser Breaks Records to Impact Oregon’s Future

“Impact Oregon’s Future,” our annual fundraiser held on October 20, had a great turnout and raised more than $265,000 for Children’s Institute. This event, emceed by CI’s Senior Early Education Advisor Soobin Oh, highlighted our work across Oregon to increase access to and strengthen critical early childhood programs and services, including preschool, home visiting, child care, and many others.

“We are so grateful for these contributions from our supporters,” said Swati Adarkar, CI’s President and CEO. “Every dollar helps us continue the work we’ve been doing for more than sixteen years, connecting young children across Oregon to vital programs and services that support their healthy development and early school success.”

Children’s Institute honored one of Oregon’s dedicated business and community leaders and long-time CI board member, Ken Thrasher, with the Alexander Award at the event. This award, named for Richard C. “Dick” Alexander, recognizes those who are committed to improving the lives of Oregon children with a focus on early childhood, and honors Dick Alexander’s advocacy for children as one of Oregon’s foremost business and civic leaders.

“Ken truly embodies the spirit of the Alexander Award,” Adarkar said. “His commitment to children and families has been exemplary and he has had an extraordinary imprint on advancing Oregon’s early childhood agenda. Ken’s deep, long-standing passion is to make a big difference for children and families in Oregon, and he has. I was thrilled to celebrate him.”

Others who added their gratitude and thanks for Ken’s service and commitment to Oregon’s children during the event included Governor Kate Brown; Martha Richards, Executive Director of the James F. and Marion L. Miller Foundation; philanthropist Jordan Schnitzer; and Beaverton School District Superintendent Don Grotting.

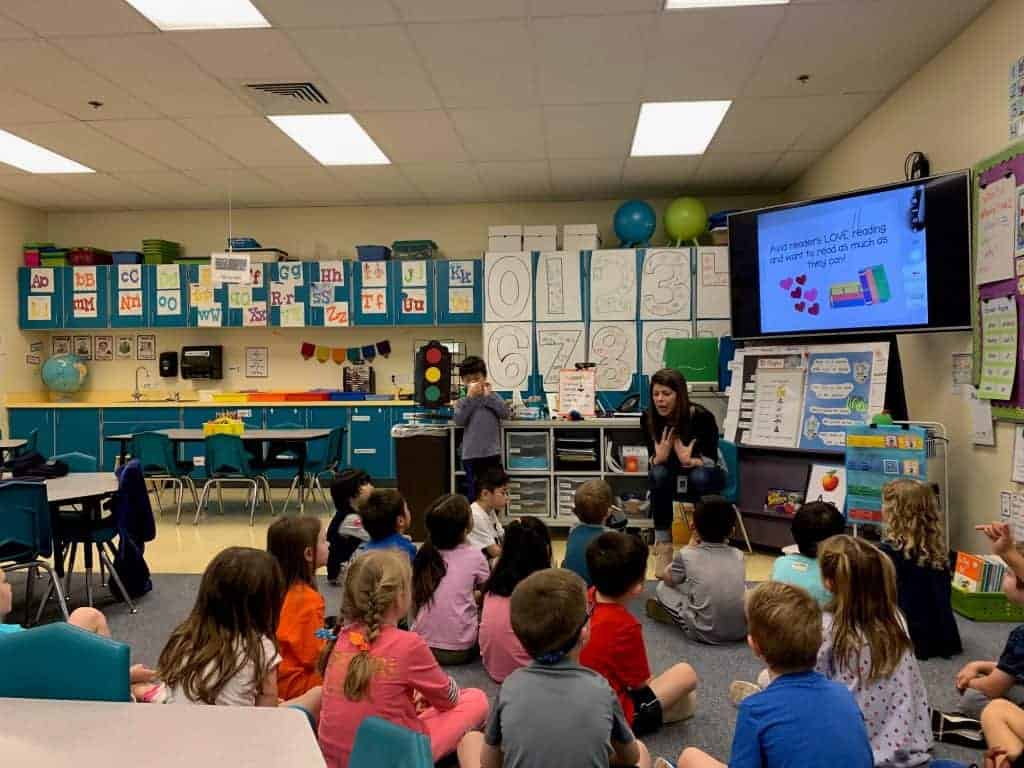

Notable projects highlighted during the event included CI’s Early Works Initiative, with sites in Yoncalla and SE Portland. Early Works schools, located in districts where children face multiple barriers that have historically resulted in achievement and opportunity gaps, connect with families before children reach kindergarten. Programs include playgroups for parents with infants and toddlers, parent education and adult learning opportunities, public preschool for 3- and 4-year-olds, housing advocates, and a community health worker that can connect children and families to much needed health and community services.

CI’s Early School Success program, also highlighted in the event, launched in 2019 and expands upon what we’ve learned through Early Works. Early School Success partners with school districts to connect the early years and early grades. The Children’s Institute team provides consultation, professional development, and coaching to support the use of developmentally appropriate teaching strategies for preschool through fifth grade.

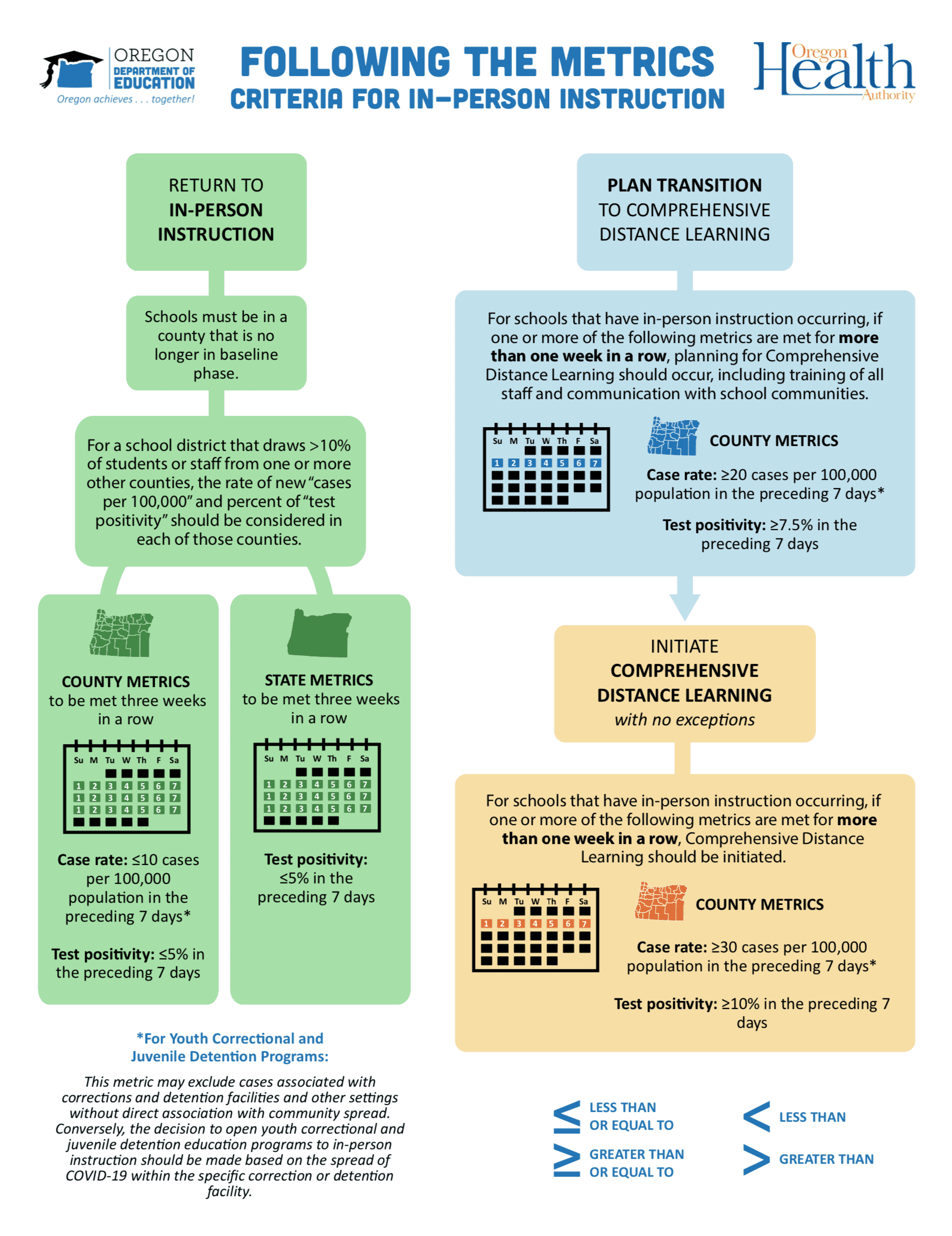

What CI learns from its program work informs advocacy efforts at the state level for public policy that supports high-quality care and education for children from the earliest ages. Important recent policy wins celebrated during the Impact Oregon’s Future event include the passage of the 2019 Student Success Act, an historic investment in Oregon’s children, providing $200 million each year to programs specifically serving the state’s youngest learners.

“It’s really incredible to witness the growth of the movement to support Oregon’s children. Strategic investment in our youngest Oregonians is a sure way to impact our state now and into the future. We’re pleased and grateful that so many people, parents, leaders, and community partners see the value of the work we do and have donated critical resources to fuel our work forward,” said Adarkar.

Sponsors for the event included presenting sponsors Cindy and Duncan Campbell as well as corporate sponsors The Harold & Arlene Schnitzer CARE Foundation, Stoel Rives LLP, Columbia Bank, Portland State University, NWEA, Education Northwest, NW Natural, Cambia Health Solutions, Pacific West Bank, Pacific Power, and Vernier Software & Technology.

Don Grotting is the superintendent of the Beaverton School District. For more than 20 years, he has led school districts in rural and urban communities across Oregon. Grotting has received several awards and accolades for his work and leadership, including 2014 Oregon Superintendent of the Year from the American Association of School Administrators. He also sits on numerous boards and advisory committees, including the Governor’s Council on Education and Oregon’s State Board of Education.

Don Grotting is the superintendent of the Beaverton School District. For more than 20 years, he has led school districts in rural and urban communities across Oregon. Grotting has received several awards and accolades for his work and leadership, including 2014 Oregon Superintendent of the Year from the American Association of School Administrators. He also sits on numerous boards and advisory committees, including the Governor’s Council on Education and Oregon’s State Board of Education.