From Kinder Camp to Classroom: A Q&A with St. Helens Early Learning Director, Dani Boylan

I’m sitting on Zoom with Dani Boylan, director of early learning at St. Helens Early Learning. This is her second year running Kinder Camp after several years of teaching preschool. Students from three schools (McBride, Columbia City, and Lewis and Clark) gather in the kindergarten classes of the latter’s elementary school, filling the hallways with joyful sounds. A student passes by the door to Dani’s room, and she’s quick to grin and say hello.

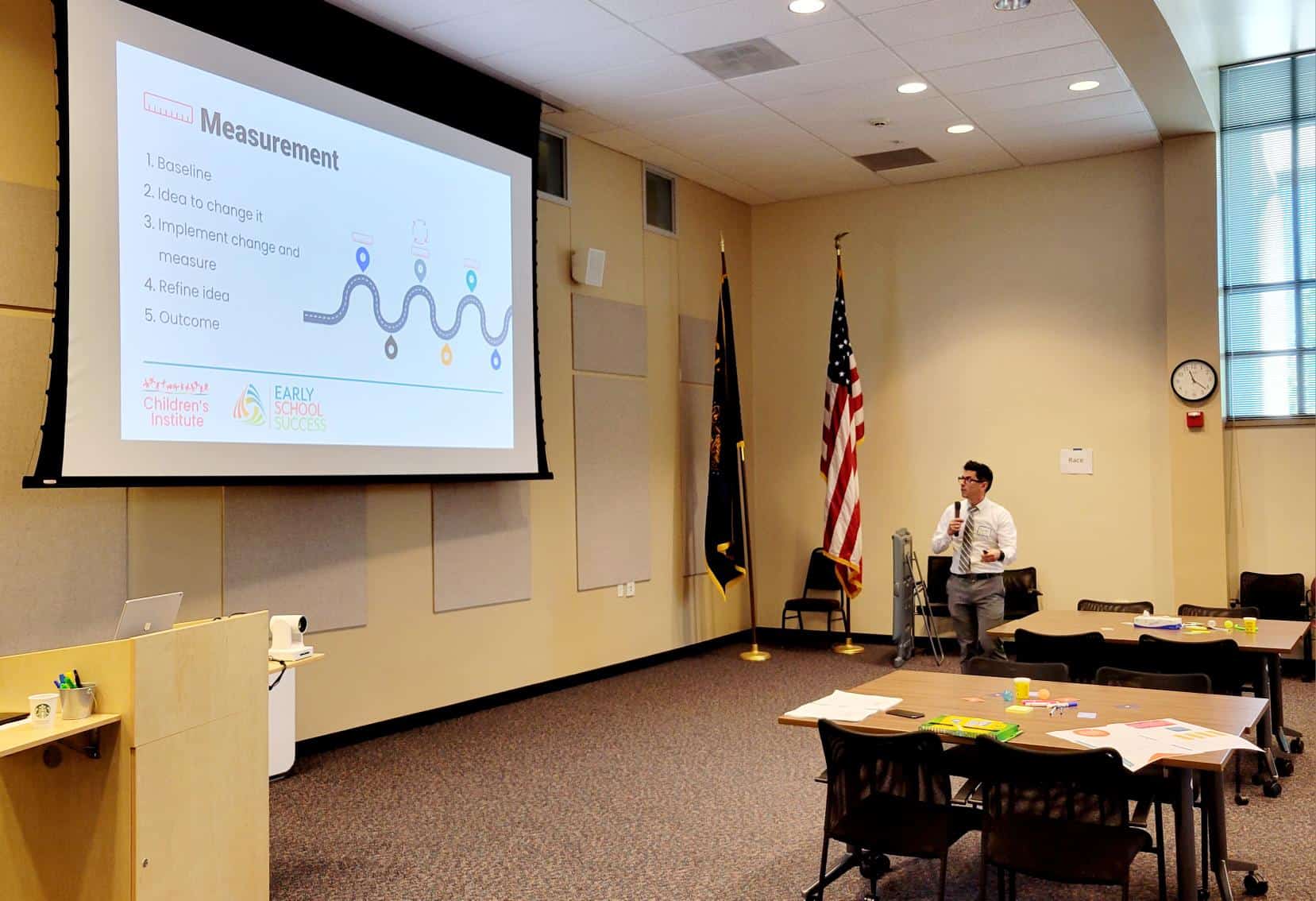

Though their program faced significant state budget cuts which limited the scope for 2023, teachers and administrators in St. Helens worked together to reorganize for the year. They made a plan that made the most of the resources available, setting up intentionally small class sizes and offering support for children with varying social emotional needs. I eagerly pull my list of questions in front of me, and we begin our virtual interview.

You taught Kinder Camp for a while before running it. Could you tell even during those early years the impact it had on kids?

100%. This is my eighth year, and as we’ve done it each year, we’ve watched it benefit kids in a huge way. Students coming in from Kinder Camp got to be those prepared kids who knew the routines, who knew what was going on once kindergarten started and how to jump into activities. It was super helpful for them to feel ready for school. Through our partnership with the Children’s Institute, we were even able to do several Ready Freddy Kindergarten events starting in February so that kids could meet their teachers before Kinder Camp began. Getting dropped off and prepared to learn with familiar faces makes such a big difference for kids starting an important year. But it was also beneficial for the staff, because as we were doing class placement for the year ahead, we could say, “Hmm, we had those kids at Kinder camp, these two students should be in different rooms,” or other similar situations. It’s been helpful for trying to even out our classrooms and get children and staff the help they need.

What do the days look like for kids?

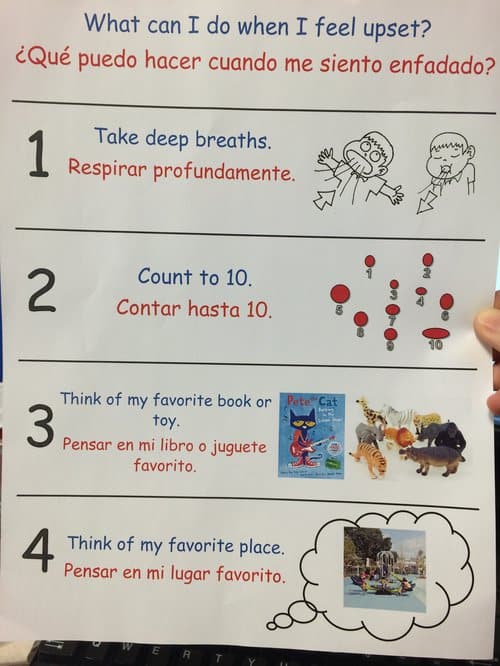

Due to funding, we moved to a half day format in 2023 rather than the full days we had in the past. So, for this year, camp starts with kids arriving and having breakfast, then heading to a classroom for circle time with a social emotional learning focus. On a given day, they might learn about the different emotional zones, like the “green monster,” and they sit and make a green monster to tangibly process the lesson. We did this on one of the days, and I asked a student what his monster was named, so he named it after me. And I said, “Well, it’s good that your monster is green, that means it’s happy!” And he goes, “That’s because you ate Baby Yoda.” That was his logic.

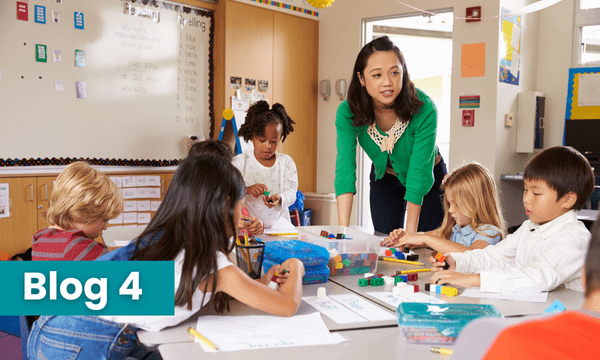

Next, the kids go and have 30 minutes of uninterrupted play with their peers. We’ve been trying for the past couple of years to get the post-preschool to understand the importance of play-based learning. To do that, we’ve introduced it into the design of our kindergarten and first grade classrooms—setting up different kinds of seating, smaller tables, options for sitting or standing, sensory tables, light tables, dramatic play. It’s a great way to keep the learning going even during free time for the kids.

After that, we have recess time, we’re able to have our STEAM teacher come two days a week and take our kids for about half an hour to do science and engineering-oriented activities, like trying out a 3D printer! Then they have lunch and head home at 12:30.

That sounds like an amazing flow to a day, I would have loved that as a kid!

I was teaching Parent Ed the other day, and one of them told me, “My kid came home after camp yesterday and said, ‘I had an amazing time at school, I just got to play all day!’” And I said, that’s exactly what we want, and I can tell you exactly what your child learned yesterday through all of that. They don’t just sit at their desk and do worksheets the whole – they get to play and build with intention. We do a lot of talk with parents about intentional play and using different materials at home to expand their child’s learning experience.

We gave them kits to bring home this year focused on social-emotional learning since it’s August and they’re gearing up to go back to school. The kit included Emotionoes, which are Dominoes with different emotions on them, and you label and match up emotions. When you’re playing it with your child, you point out the emotion, ask the child to mimic it, and even ask questions about what they think happened to make the person feel that way. Those questions help guide the kids toward social-emotional learning.

We also talk about how even simple toys, like shape blocks, can be turned into so many things with intention. You can learn math, literacy, social skills…I told the parents, “You can tell me any object that your kid likes to play with at home, and I can tell you three different ways you can turn it into social emotional learning.” One of the moms was like, “Okay, I dare you. My kid likes those little cubes that you can stack together to build people, cities, anything. How does that turn into social learning?” So, we talk about how, when they build the people, notice or give them personalities. And when those characters start to take action or attack another character, ask why they are doing it, or why they are upset. Ask what’s happening in the setting, or pick up a character and introduce their feelings, too. Then ask your kid what they would feel like under those same circumstances. Those questions teach kids to observe experiences, to understand the underlying emotional states of a situation, even if it is make believe.

The parent responded with, “Wow, you really can come up with a way to learn from anything,” and I responded, “I’ve been teaching for 26 years. I didn’t just randomly pick up objects and know how to do intentional learning, it took time.”

It’s great that our district is starting to understand the importance of social emotional learning. Last year, we got these cabinets to fill with loose parts. Even our title class has gotten involved as a part of our Children’s Institute grant, so we’re figuring out how to incorporate loose parts into title, too. For example, reading a story and then sitting down and trying to figure out, okay, if these are the different parts, how would you create a scene from the book, or use puppets to act out a different ending? It’s really nice to get the different parts of our school involved in what we’re starting out in our preschools and kindergartens.

It seems like it just moves all the way up with continuity for kids, families, and teachers. It’s amazing.

It really helps that our administrators and our Superintendent is 100% onboard and supports early learning. He meets with me regularly to ask what we need from him and how the district can support us more

So, for social-emotional health – that seems like something that’s come to the forefront more recently. When did you start to see it prioritized in the district?

I started to notice in the past six years that it was becoming more of a priority for us. Our district specifically started promoting relationship building in the first six weeks of school, recommending that teachers focus on establishing connections with kids before emphasizing academics. It’s vital to show them how to connect so that they can have a safe space to learn throughout the year.

I had a parent come to me about it the other day, saying how a lot of kids now are coming in with ISPs for social emotional learning and how it’s connected to COVID. And, yes, the entire population suffered socially-emotionally from not having those early social connections. But I also wonder, how many kids with these struggles are just getting identified sooner? While more kids are coming in on ISPs, they are also being identified sooner because of Preschool Promise and Head Start. Having more programs allows more kids to get those referrals ahead of time.

When I ask kindergarten teachers what they want us, as preschool teachers, to teach their kids, they ALL say social emotional learning. They say, “We can teach kids letters, numbers, anything. Kids are sponges, they’ll pick it all up when they’re ready. But if we can’t have a group sit down and listen to our lesson or have problem solving skills with each other or walk in a line with their peers, it takes much longer to be able to teach the class. The more they can have those skills coming in, the faster the other aspects of learning can fall into place.

Thank you so much for unpacking that, wow. And it totally makes sense, kids have to feel emotionally safe to connect with each other and learn.

Yeah, exactly. When kids know they’re safe to make a mistake, that they can hit the reset button if something gets difficult… they’ll be 100% a different kid with you. We have one kid right now who can show aggression sometimes or run out of the building in some settings, but for me, he’s never showed those behaviors because we’ve been able to build a relationship where he knows he’s safe. All these kids come from different places or with trauma from different things. And the adults, the teachers, come with their own trauma too. So how do we make sure our own trauma doesn’t impact kids? For instance, a teacher may be triggered when a kid swings at them. And to be able to recognize that, and make a classroom switch as needed, is critical. Kids need to know that it’s okay to mess up and try again.

Are there other school programs where you’ve found inspiration for what you do at Kinder Camp, or have you and the other teachers sort of carved your own path with it?

Well, I think the way Kinder Camp works has pretty much been established across the state as far as the basics goes, the requirements for using grants. There are key things to keep, as well as places to be flexible. For example, with parent ed, sometimes it’s multiple days or weeks. Other times, we have to condense it to the key things they need to know and learn. which is where things like take-home kits come into play.

It’s so cool the way you provide ways for parents to get involved, not just by telling them what’s going on but also with training and providing support materials along the way, so they have hands-on learning through your expertise.

Each year we make tweaks. Something we’ve learned is that, with smaller classrooms, it doesn’t matter how many kids we have in there with different needs – with smaller groups, each kid is able to get the assistance and support they need.

What are some other ways you hope Kinder Camp can grow over the next couple of years?

It would be nice to be able to have more classrooms because we do end up having a wait list every year, and parents try to sign up right up until the camp begins. Ideally, I would love to have it at their actual elementary schools, which can be difficult to navigate with transportation, but there are benefits to kids being able to be in their own school. But funding is the biggest challenge and need for us as we look to grow. Having the Children’s Institute this past year helped us with support and providing more access to funding, but it all comes back to how important the transition is between preschool and kindergarten. Those kids need as much time in the classroom with their teachers and peers as possible before the school year begins.

What’s something you would want everyone to know about Kinder Camp?

If you have the opportunity to send your kid, even if they’ve been in preschool before, you should do it. Because it gets them with the group they’re going to be in school with, it gives them a chance to meet their teachers, and it provides a heads-up on how their routines will work and what activities they’ll be doing as the school year begins. That way, starting on the first day of school, kids come in feeling like they know what they’re doing and what comes next, which is incredibly beneficial for them. It’s never a bad idea to give kids more of an idea of what their education is going to be and feel like.

Where do you get your inspiration and energy for the work you do every day?

It comes from the kids. If you just watch and listen to them, they will tell you exactly what they need. They’re all you need to figure out what to do. Even our kids who struggle, if you put them in a different environment and they do a little better, then you know what the problem was. It’s not about these kids struggling, it’s about the environments we’re creating not being right for them. So we have to listen to them.

Also, I get a lot of inspiration from my former admin who is now one of the principals in our district. She ran early learning for years, and now she’s principal and I took over for her. She’s been my mentor for years, so Martine Barnett helped me figure out exactly what I wanted to do with this program and how to navigate my first time running it. She ran it while I was a teacher here, so she was there for me whenever I had questions and needed to figure something out.

Awesome, well thank you so much! The work you’re doing is incredible, and I really appreciate your unpacking the vision behind Kinder Camp and how it impacts kids. Keep it up, and I hope the programming wraps up well for this year!

Preschool for All first welcomed county children in fall 2022 after voters approved the November 2020 measure to expand early education to young children. The program is funded by a marginal personal income tax on the county’s highest income earners and has generated more than $187 million since its inception through June 2022.

Preschool for All first welcomed county children in fall 2022 after voters approved the November 2020 measure to expand early education to young children. The program is funded by a marginal personal income tax on the county’s highest income earners and has generated more than $187 million since its inception through June 2022.