CI Joins Amicus Brief in Supreme Court DACA Case

In an amicus brief filed last Friday, 36 organizations and leaders, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children have asked the court to consider that a reversal of DACA protections would cause developmental, psychological, and economic harm to at least 250,000 children in the U.S.

Oregon is home to one of the largest populations of DACA recipients in the country, with 9,910 DACA residents and 5,500 children of DACA recipients.

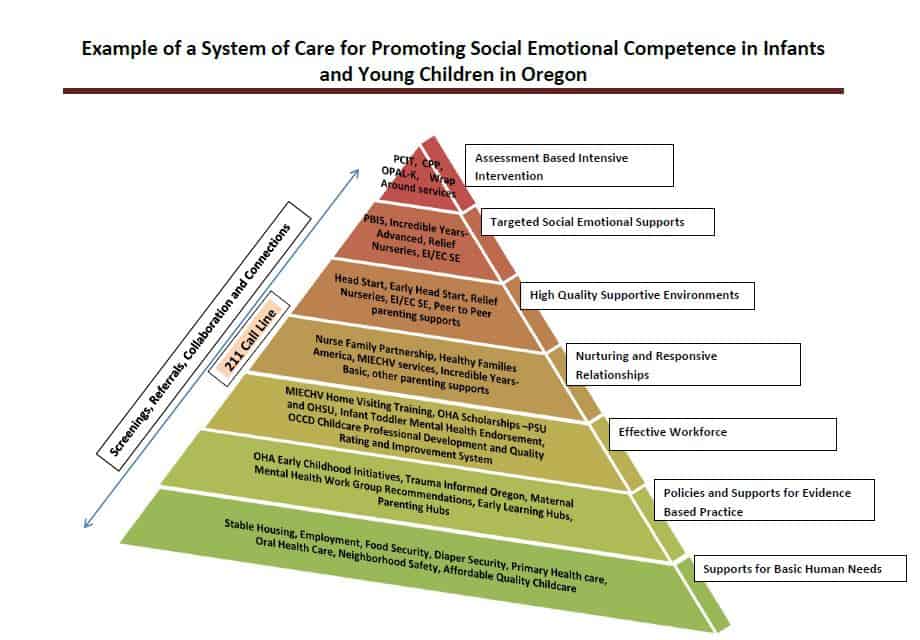

The brief states in part, “The imminent threat of losing DACA protection places children at risk of losing parental nurturance, as well as losing income, food security, housing, access to health care, educational opportunities, and the sense of safety and security that is the foundation of healthy child development.”

The DACA program began in 2012, under President Barack Obama. DACA recipients, also known as Dreamers, are children of undocumented immigrants brought to the United States as minors. DACA allows recipients to work in the U.S. and protects them from deportation in renewable two-year increments.

Research has shown that DACA has increased the wage and employment status of DACA-eligible immigrants, improved the mental health outcomes for DACA participants and their children, and reduced the numbers of households living in poverty.

Understanding that the hearts and minds of our children hold the greatest promise for our nation’s future demands that we protect DACA policies which keep families together, effectively and appropriately prioritizing the needs of our youngest.

– from the amicus brief, Children’s Institute