Governor Kotek Visits Yoncalla Early Works in Douglas County

Governor Tina Kotek visited Douglas County as part of her One Oregon Listening Tour where she plans to visit all of Oregon’s 36 counties during her first year in office.

On Friday morning, she stopped at Yoncalla Elementary School’s Early Learning Center—a demonstration site for Children’s Institute’s Early Works program, which launched at the school in 2013.

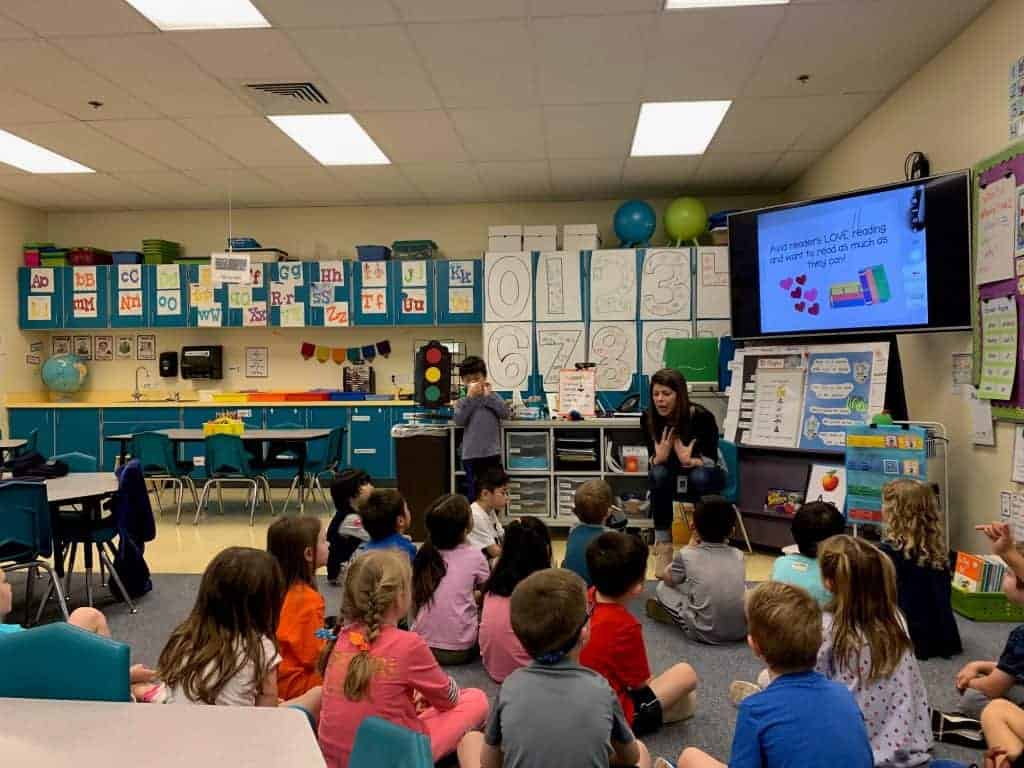

Governor Kotek toured the early learning classrooms with preschool director, Megan Barber.

Barber guided Governor Kotek around each classroom, pointing to the various enrichment spaces for reading, STEM, and art, as well as areas for children to have quiet time and develop social-emotional skills.

She described the tight-knit relationships that children and their families have with teachers and school staff, sharing that before the beginning of each school year school staff does home visits with all the families that have children attending the Early Learning Center.

Governor Kotek warmly thanked Barber for sharing and told her, “Every community deserves this.”

Governor Kotek warmly thanked Barber for sharing and told her, “Every community deserves this.”

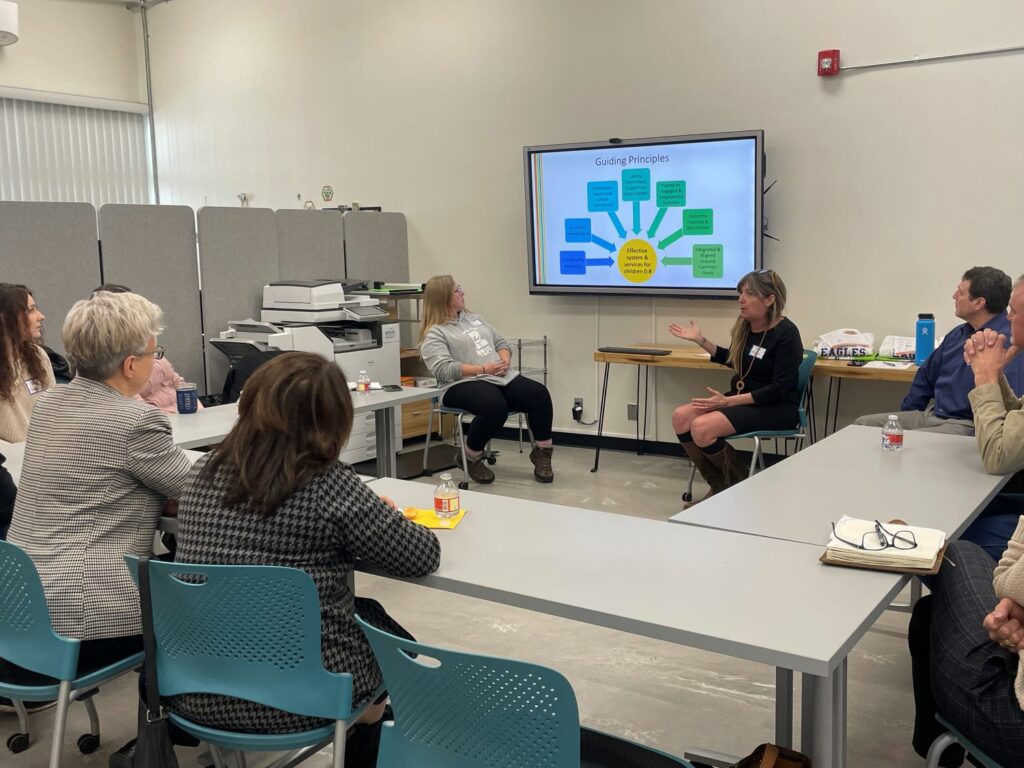

As the classroom tour came to an end, parent leaders, educators, and community members gathered in the kitchen/community space for a roundtable discussion about Early Works and the impact of a strong early learning program on children, families, and the community.

During the roundtable, Sara Ruiz-Weight shared how Early Works impacted her family.

“I started to realize what it was like to be part of a school family. I started to realize what it was like to be able to have help outside of my family. And so, it just became something bigger than what I ever expected,” said Ruiz-Weight. “Once you start to support families in small communities, they start to realize what their value really is,” she said.

There were few dry eyes as the room filled with stories from parents, grandparents, teachers, and community members.

One theme rang loud and clear – the school is the hub of this community, and a place where children and families can meet their needs.

Erin Helgren is the principal of Yoncalla Elementary School and the Early Works site liaison for Children’s Institute. She explained to Governor Kotek that the school’s early learning program is community-centered, community-driven, and that the focus should be on strengths, not deficits.

“This project is not grounded in poverty and what this community doesn’t have, but it’s grounded in what it DOES have.” said Helgren. “The foundation is justice and love, and feeling safe, and feeling connected. This is not head work, this is heart work,” she said.

Governor Kotek nodded thoughtfully and responded, saying, “It’s about the assets of the community, and the strengths that you have. It is about having community lead that transformation.”

She also said that, as governor, it is her job to listen and find ways to make it easier for communities to do what they need to thrive.

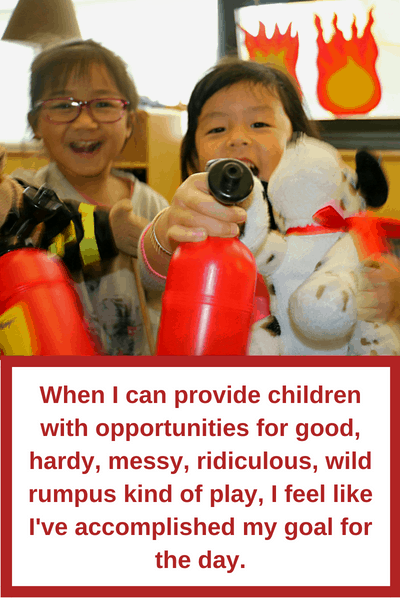

I will also admit, I’m deeply in love with preschool because I get to play. It was shocking to me that I had forgotten how to play—silly, crazy play—like children do. Learning real play again became a study of mine, something I practice and invest in. You see, play is where the magic is. Anything can happen for children in play! And when I can help provide children with opportunities for good, hardy, messy, ridiculous, wild rumpus kind of play, I feel like I’ve accomplished my goal for the day. What was so strange to me was realizing that some of the children coming into the classroom forgot how to play. That is all the more reason why play is an absolute necessity, because it creates a space where children bloom and come into their own. We teach children how to use their imagination, how to think deeper about what they are doing and seeing, and how to engage with peers to make their experience more fun.

I will also admit, I’m deeply in love with preschool because I get to play. It was shocking to me that I had forgotten how to play—silly, crazy play—like children do. Learning real play again became a study of mine, something I practice and invest in. You see, play is where the magic is. Anything can happen for children in play! And when I can help provide children with opportunities for good, hardy, messy, ridiculous, wild rumpus kind of play, I feel like I’ve accomplished my goal for the day. What was so strange to me was realizing that some of the children coming into the classroom forgot how to play. That is all the more reason why play is an absolute necessity, because it creates a space where children bloom and come into their own. We teach children how to use their imagination, how to think deeper about what they are doing and seeing, and how to engage with peers to make their experience more fun.