Rafael Otto: (00:08)

This is the Early Link podcast. I’m Rafael Otto. With schools closed and students and teachers working to stay connected and learning online. I wanted to talk with a teacher about what that experience is like. Janice Lewis joins us today on the Early Link podcast. She is a veteran teacher at Vose elementary in the Beaverton school district. Welcome Janice.

Janice Lewis: (00:28)

Thank you. Thank you for having me.

Rafael Otto: (00:30)

Glad you could join us today and for our listeners this episode will air on Mother’s Day. So Janice, I just wanted to wish you a happy mother’s day. There’s an interesting story about how you came to teaching. Tell us about that, how you became a teacher.

Janice Lewis: (00:44)

Well, it’s not a very direct route. I went to college right after graduating from high school but really didn’t have any focus or direction and ended up not finishing school and I got married relatively young. I was 22 and very shortly after that I was able to be a stay at home mom, which is something that I had wanted to do. So it was very fortunate that I was financially able to and that it was something I loved and enjoyed. But as my children were growing up, I could see this end date to that job coming as they would leave home. And I had found mothering to be a very, very purposeful and fulfilling activity and I wanted to continue having purpose in my life. So I went back to school and I got a bachelor of science in human development and also a minor in social work.

Janice Lewis: (01:33)

And in my social work classes I found that I was very, very drawn to families living in poverty and in particular children who live in poverty. I read a lot of books during that time by Jonathan Kozol who you might be familiar with. He writes beautiful, beautiful stories of children living in poverty that just really tug at your heart. And so I thought that I would work for a little while and then go on to become a social worker, get a Masters in social work. I took a job with Head Start because then in that type of job you work with children and with families. But once I got into the job, I found that I fell in love with the teaching part of it more than the interaction with the families. So I eventually went back and got a Masters in teaching and an ESL endorsement and decided that I would instead have a career in teaching and I set a goal of working with children who live in poverty through an elementary school experience. And so I have spent my whole teaching career working primarily with immigrant families and families who live in poverty.

Rafael Otto: (02:41)

You’ve been a preschool teacher now for a number of years? Correct. Did you teach elementary grades as well?

Janice Lewis: (02:47)

Yes, I had five years as a Head Start teacher. After I got hired in the Beaverton school district, I had one year as an ESL teacher and found very quickly that I really didn’t care for that because I didn’t have that classroom bonding kind of experience that you have when you’re a classroom teacher. So I was very fortunate that the following year, a first grade job opened up and I taught first grade for a number of years and loved it. And then I’m just back into Pre-K again the last three years. When that opportunity came up I thought, wouldn’t it be a nice way to end my teaching career? Going back to something that I loved a long time ago.

Rafael Otto: (03:31)

Tell me about the number of preschool classrooms that are available in Beaverton.

Janice Lewis: (03:40)

There are seven currently. Each site has a morning and an afternoon class. So it’s growing, but it’s still very, very small percentage of the number of four-year-olds in our district who are able to get that high quality preschool experience.

Rafael Otto: (04:08)

How does the preschool stay connected to what’s happening in the elementary grades?

Janice Lewis: (04:13)

Well that varies from school to school. At Vose I am in the best possible situation. I have an excellent principal, Monique Singleton and an excellent vice-principal, Melissa Holz who both absolutely understand and support the value of early learning. So they have fostered a lot of connection between pre-K and the upper grades. For instance, featuring what we’re doing at staff meetings, asking upper grade teachers to come in and see what we’re doing and build on the really good things that are happening in pre-K. And this year I’m in the kindergarten wing so I’ve had a lot of opportunity to collaborate with the kindergarten teachers as they are trying to do more of what we’re doing in pre K and it’s been a great experience. I already had a relationship with those kinder teachers because I had taught first grade for so many years and just highly valued. How well prepared the students were when they came to me. So had a good working relationship already. But this year it’s been different because they’re all dabbling into inquiry and it’s just been wonderful to collaborate with them and help them discover what a great way of teaching this is.

Rafael Otto: (05:27)

I’m curious about in the current time as we’re moving digitally and trying to connect and try to keep kids engaged and learning what that’s like as a preschool teacher and what have you come up with for remote learning options for children and is that possible? How is it working?

Janice Lewis: (05:42)

It is possible, of course it’s not the same as having those children with you in the classroom, but it is possible to keep the connection going. So what all of the preschool teachers are doing is we are filming short videos and posting them on a platform called Seesaw and parents can access them at whatever point in the day they want. So that’s different from what a kinder through fifth grade student is experiencing at Vose where there are set times for a class meeting or Zoom small group. I usually load three videos first thing in the morning and then I load another one a little bit later in the day. That’s kind of like a little bonus or an extra and it’s just really incumbent upon me as the teacher to think of things that the children will be drawn to. And fortunately with the weather being the way it is and with it being spring time, there’s just so much to access.

Janice Lewis: (06:41)

I started a garden with the children before school let out. So I am continually going over to the garden and filming what’s happening and posting questions for them. Just as an example, I went to check on the garden last week and we planted only pea seeds, but right in the middle of the garden there’s a little Oak seedling and a little farther down there are some tomato plants growing, neither of which did we plant. The fabulous thing about the Oak seedling is that we have a giant Oak tree on our property and the children are fascinated with that tree and have thought all year long that fairies lived there and they’ve built fairy houses and told stories about it. And so I pose the question, how did these things get into our garden? And of course some children immediately thought that the fairies must be behind this.

Janice Lewis: (07:30)

The children answered back with, with things like, well, some seeds must’ve gotten mixed up at the seed packing factory. So I’m still presenting them with things that they find engaging and I’m posing questions so that they will think and wonder and then they respond to me. So it is possible to find things that will draw them in. And just like in the classroom, I have to provide a variety of learning experiences. So I’ve had building invitations and storytelling invitations and um, mathematical games. So, you know, you just never really quite know exactly what’s going to draw a child in so it has to be a variety of offerings. And overall, it’s a pretty good time of year and a pretty good place to be. Indeed. I had the good fortune of a Robin who decided to nest right outside my front door and that’s been fascinating.

Janice Lewis: (08:24)

So we were doing a little study of nests where I had just have, I love birds nests and I have a big collection of them. And I did a nest making invitation for the children to use mud and sticks and different things to create nests. I was filming a nest that was by my front door and then I started noticing that it was changing every day. And sure enough, our robin was nesting. So about once a day she’ll hop off long enough for me to get a little snapshot or a video of what’s happening. So the children are very interested in that.

Rafael Otto: (08:56)

I can imagine that they would love that.

Janice Lewis: (08:56)

Yes, they do. I’m very thankful that when I discovered that nest starting to change. It was just like the most beautiful gift in the middle of a really awful situation because that was quite a while ago and it was when the pandemic seemed so scary and so grim and yet this beautiful, lovely thing was happening right outside my front door. I just was so thankful for it.

Rafael Otto: (09:29)

That’s wonderful. What other kinds of things are considered developmentally appropriate in terms of children’s learning during this time and are what other kinds of curriculum ideas or are you using or what other standards are you trying to apply?

Janice Lewis: (09:44)

Well, we use a framework called Habits of Mind and I don’t know whether you’re familiar with that, but what we are trying to focus on with children is things like persistence, collaboration, focus skills that they build into their mind, their framework that will serve them as they go into kindergarten and beyond. In addition to that, we also have some more what you would think of as typical school standards, like writing your name, being able to count to ten one to one correspondence, counting, counting to 20 and sequence recognizing numerals and that type of thing. So I’m doing really a balance of inquiry, such as what I referred to with the garden and then more skill work, but still in a way that’s engaging to preschoolers. So for example, this week we’re doing an overall study on texture. So finding texture in things in your home and outside, doing some texture painting with plants. So my name practice activity is writing your name in different textures of substances. So that could be a food substance like flour or salt or rice. But we also always want to offer a non-food substance just because of families living in poverty are often facing food insecurity. So I also showed how you could do that in gravel or in bark chips or in dirt. And so it’s a way to tie into our theme of texture and it’s just a way for them to have a fun, engaging way to practice writing their name.

Rafael Otto: (11:19)

I’m curious if you’re concerned about the amount of time that kids are spending on screens now that they’re interacting with their teachers more often. Are you concerned about that? Do parents have questions about it? What’s happening there?

Janice Lewis: (11:31)

I haven’t had questions from parents, but I am concerned about it and not in terms of what I’m posting because my videos are short. Anywhere from a minute to the longest. One I think was seven minutes, so really no more than a total of maybe 15 minutes of video in a day. And then the things that I’m asking to do often involve going outside and going for a walk and looking for things. So there, I don’t have a concern about that, but I am concerned that potentially children are on a phone or a Chromebook and just doing things like playing games. It’s a long time to be at home and be away from school. And of course parents are working and have many stressors on their mind. So I do think that that is a bit of a concern. Children having too much screen time.

Rafael Otto: (12:21)

Is there any kind of standard or advice that you would give people other than to try to limit?

Janice Lewis: (12:27)

I would certainly try to encourage people to do things other than screen. Like just simply going for a walk. You can get out for a walk and notice things that are growing. You can go out for a walk and close your eyes and listen and see what you hear. You can read beautiful literature. Some of it has to be accessed online because if you don’t have a large library at home, you’re going to rely on YouTube or the library. But even so that’s better than playing a game. It is a reason that a lot of the invitations that I’m creating for the children involve being outside and doing things like the nest making activity that I refer to going around, you know, collecting things that a bird would use. Mixing mud. Um, so definitely things that engage a child and thinking and wondering like we do in the classroom are preferable to being on a screen.

Rafael Otto: (13:19)

As a preschool teacher. I’m curious about the idea of family engagement and what that means to you. And I’m also curious if that has changed over time given the breadth of your experience and in your career. Does it look different now than it used to?

Janice Lewis: (13:34)

Well, it’s definitely different in preschool than it is in first grade. I would say I had virtually very, very little contact with first grade parents. It was at the beginning of the school year and then at conferences. And really that was about it. I knew my students really well, but I really didn’t know their families. So with our preschool model, we do three home visits a year and two conferences and versus a walking school. So I often see parents dropping the children off and picking them up. So there is that engagement. We don’t have a high rate of volunteerism at Vose. And that’s because parents are often working sometimes multiple jobs just to survive. So they don’t often have the luxury of time to be in the classroom. Another silver lining in what’s happening right now is that I am having way more communication with my families than I had when we were in the classrooms.

Janice Lewis: (14:31)

So families are really needing a lot of help. They’re needing encouragement, they’re posting things on Seesaw for me to look at and I always respond, you know, to the child or to the parent and we’re celebrating things more. I got pictures just the other day of a little girl who was having a birthday party and there have been couple of babies born in our classroom and we’re all celebrating that. So I honestly feel that I have more engagement from my families right now and I think that’s a really interesting thing to ponder. What could we do when school resumed and something you know, things to do that would create a stronger bond between the families and the school. I think that that really needs some thinking. Sure.

Rafael Otto: (15:15)

What else are you seeing in terms of what parents and families need most right now during this time, specifically with the COVID-19 pandemic,

Janice Lewis: (15:24)

There are needs that they have that are really concrete. For instance, I need a Chromebook for my child, which our district has provided for anyone who needs it or I can’t log onto my Chromebook. Can you help me with my password? My child doesn’t want to participate. How can you help me? So there are concrete needs, but what I’m hearing oftentimes under the questions and just comes about in a roundabout way that parents need to be encouraged. Right now we are asking a lot of parents and particularly in our community where people are living on the edge anyway. If you’ve lost a job, it’s very, very serious and we are also asking parents to be teachers at home. Even at this preschool level, there has to be a certain involvement with the parents. And so I have found myself messaging parents through Seesaw and just thanking them. Thank you for continuing to make sure your child is learning. Thank you for sending me those pictures of your child’s birthday party. That was so delightful to see and I find myself saying things like, you are such a great mom. You’re doing such a good job, and the response that I get back when I say things like that shows me that these parents are really hungry for that. They need to be encouraged that they are enough. What they’re doing is enough. Their children are going to be okay.

Rafael Otto: (16:49)

It’s interesting that during this time during the pandemic with parents and families having to balance so much that the role of the teacher, the need for skilled teachers is becoming more and more apparent and that there’s just this recognition of the importance of the teacher in children’s lives.

Janice Lewis: (17:07)

Yes. You definitely see that often in very comical ways where you’ll see a funny clip on YouTube about people saying they had no idea what it was like to be a teacher. So I do think maybe, I mean I know that the parents that I’m serving are extremely grateful and thankful. I hear that often from them. So maybe in general as a society maybe there will be a little bit more appreciation for the career of teaching. It’s definitely a hard job, but certainly one of the most rewarding that I think you can have.

Rafael Otto: (17:39)

I hope so. When you think about the idea of a grade level meeting, groups of teachers getting together to think about strategies and how to work with their children, how to make adjustments, how to engage their parents and families. What does that look like at the preschool level and in Beaverton?

Janice Lewis: (17:58)

Well, in Beaverton we have a really strong team. The seven of us who are preschool teachers, even now we still have weekly meetings. So we have a weekly Zoom meeting, but we also have a text thread where we text each other all week long and if someone comes up with a great idea, they’re willing to share it. We have a shared Google drive right now where we are uploading any lessons that could be generalized to another school. So they’re still definitely collaborating. They’re sharing. We have some wonderful TOSAs that help us at the meetings and they’re conveying information from the district information from the state and kind of distilling it down to the pre K level because pre-K is a really very different grade level than even kindergarten, so I still feel as if we have a strong team connection and a lot of support.

Rafael Otto: (18:50)

Have you looked ahead at the fall and thought about what that might look like? I know there have been many different kinds of scenarios. People are talking about possibly staggered openings or restructuring the school day in a different way. Have you thought about that? What does that look?

Janice Lewis: (19:05)

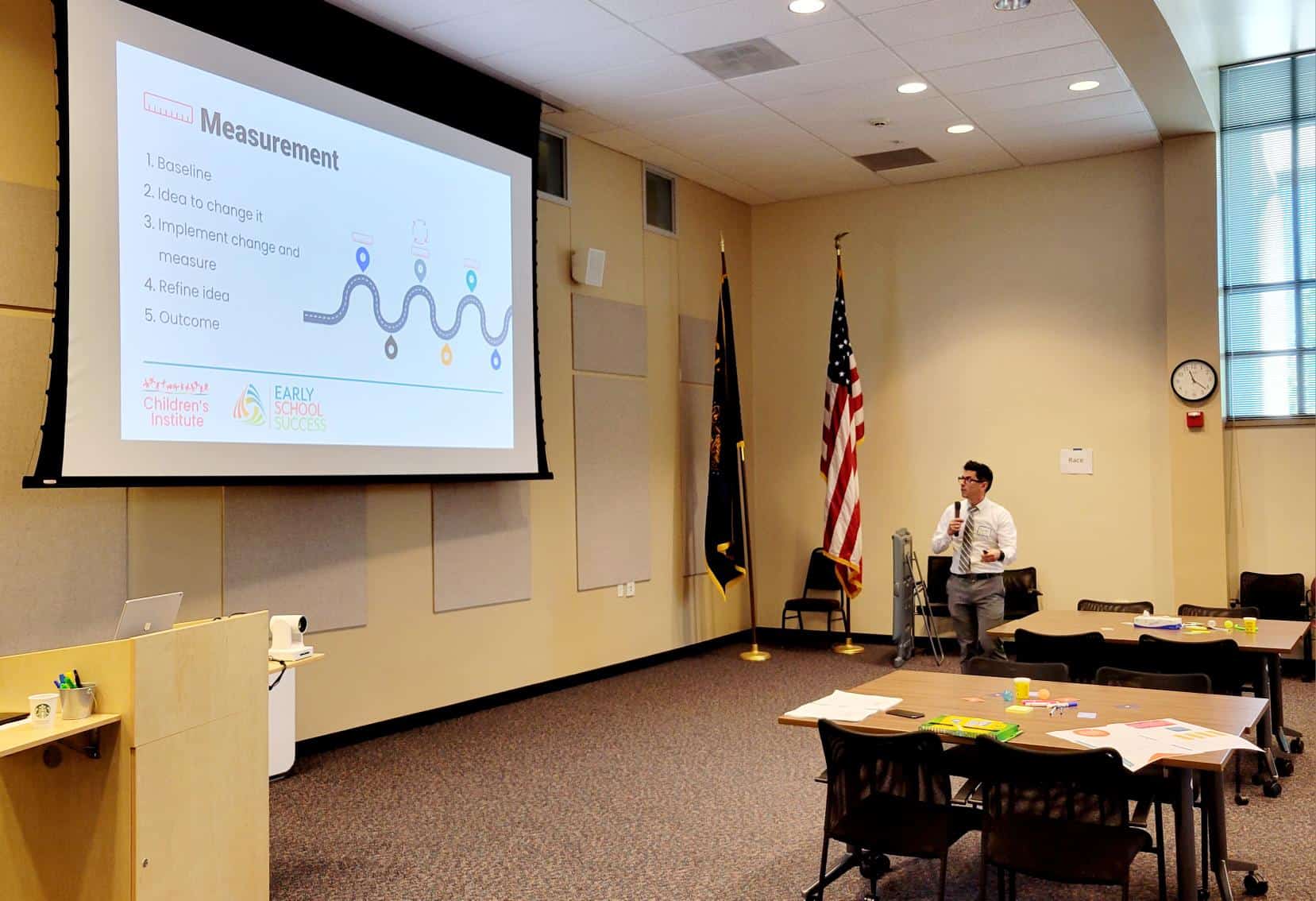

I think there’s a lot to be concerned about. I think primarily what I focus in on is the budget shortfall, it seems apparent that teachers could lose their jobs. There could be large class sizes in Beaverton. There’s a very, very strong initiative right now in early learning to take the inquiry model that we’ve created in pre K and move it up to kindergarten next year. That’s a lot of the work that we’re doing with the Children’s Institute right now and then from kinder to first and so on. I I just have a little concern about that continuing to go forth smoothly. If there are lots of teacher layoffs or if there is a staggered start, I know that our district has a very, very strong commitment to inquiry and I just don’t want to see that momentum start to fail.

Rafael Otto: (19:58)

Janice, you’re referring to the Early School Success program, which is a Children’s Institute program. Part of what that program is designed to do is connect preschool to the elementary grades. I’m curious, when you talk about that inquiry approach, what does it take to scale that up and embed that into kindergarten, first grade and beyond?

Janice Lewis: (20:20)

Well, fortunately we have some really, really smart, passionate people in our district who are already working on that. And I was just on a Zoom alignment team meeting where we got to peek a little bit at some proposed kindergarten schedules, some supports that are going to be put into place for teachers to access who have never taught in an inquiry model. Often kindergarten teachers want more child-directed learning. They want to see joy and learning, they want to see more play, but their question is always, how do I do that? What does that look like? Where will I get the supplies? So the alignment team that I’ve been a part of this year has been working on that for a year and their proposed schedule that we saw yesterday allows a large block of time for inquiry for children. So very child-directed learning. And I think that not only is that just a beautiful developmentally appropriate way for children to learn, but I think it’s going to be very necessary for this group of children who come back to school hopefully in the fall because many of them are experiencing trauma right now. They’re going to be hungry for places that feel safe and where they feel competent and where they feel valued and where they can build community and inquiry is the perfect platform for all of that.

Rafael Otto: (21:45)

I know that children may be experiencing trauma [from the pandemic] though they might not able to express it. It seems like it may take some time for us to understand the full impact of this on our kids. Do you agree?

Janice Lewis: (21:57)

I absolutely do agree and my husband and I have talked about that a little bit. Children are resilient thankfully, but I do think that we will see some impact on children. I certainly know that I am seeing that in some of the children that I can think of. In my preschool class where I had a mom I was messaging with that her daughter really isn’t responding to any of the invitations and I just offered, is there any way that I can help you? And she said to me, she just says she doesn’t want to do it. She misses her teacher, she misses her friends, and she wants to know, when can I go back to school? This is very big information for a preschooler to process. They don’t really have the ability to understand why this has all come to an end, this wonderful, safe, engaging place that they got to go to several days a week. I had another little boy who wouldn’t come and join in the Zoom meeting and his mom was reporting to me that he’s having temper tantrums and meltdowns and that just was not the personality that we saw at all in the classroom. And so it’s definitely impacting children.

Rafael Otto: (23:02)

Do I have this correct? This is your last year you’re about to retire?

Janice Lewis: (23:06)

Yes. Retiring from teaching. Hopefully not retiring from the work of early childhood. I’m hoping there will be a way to stay involved in the work.

Rafael Otto: (23:14)

Looking back, what would you have done differently knowing what you know now?

Janice Lewis: (23:22)

I’m thinking of when I taught first grade and if I could go back with the knowledge that I have right now, I would do much less hand-wringing and have hopefully much less anxiety about getting every child to benchmark in every subject. There is so much pressure on teachers for every child to succeed and yet children are all individuals. They’re all on their own learning continuum. And I would do more celebrating any milestone that a child made. And one of the beauties of being back in preschool is that ability to look at every child as an individual. And maybe there’s a child who’s an amazing builder and another who’s an amazing artist and you know, a child who’s already reading there, they’re just all over the continuum of learning. And I think it’s unrealistic, particularly in first grade to think that every child will get to benchmark in every subject. And I would love to be able to go back and have done more celebrating whatever milestones any particular child made.

Rafael Otto: (24:29)

Thinking about education and opportunity. And you have a lot of experience working with families living in poverty. And dual language learners. What is your hope for Oregon and what do you feel like, what’s in your view should our priorities be as a state?

Janice Lewis: (24:44)

Well, my hope always for every child is that every single year they have a teacher who is passionately committed to them as an individual and committed to them to their success. And I do think that the inquiry model that we’re building in Beaverton is a really appropriate model for young children. I would love to see that grow in our district. I would love to see that grow go nationwide. I think the idea of children, particularly kindergartners or first graders spending long periods of time sitting at a desk is just not the best way for children to learn. One of the discussions that we had with Children’s Institute was about the fact that children of poverty are often tracked into skill programs where they are focused on learning those hard skills but not learning the skills of inquiry. And to me that just seems absolutely backward. I think that they should have the same opportunities as a child who comes from a higher socioeconomic home. The things that they maybe are not able to have outside of the classroom because their families can’t provide them. I think it’s incumbent upon schools to provide that for the child in the classroom.

Rafael Otto: (26:02)

Janice, I couldn’t agree with you more on that. I wanted to thank you for your time and I appreciate you coming on the Early Link podcast today.

Janice Lewis: (26:10)

Absolutely. Thank you so much for having me and thank you for the wonderful work that the children’s Institute is doing. It’s been such a pleasure to work with CI.

Rafael Otto: (26:18)

It’s great to hear that. Thank you Janice