The Impact of Early Childhood Education with Don Grotting

Don Grotting is the superintendent of the Beaverton School District. For more than 20 years, he has led school districts in rural and urban communities across Oregon. Grotting has received several awards and accolades for his work and leadership, including 2014 Oregon Superintendent of the Year from the American Association of School Administrators. He also sits on numerous boards and advisory committees, including the Governor’s Council on Education and Oregon’s State Board of Education.

Don Grotting is the superintendent of the Beaverton School District. For more than 20 years, he has led school districts in rural and urban communities across Oregon. Grotting has received several awards and accolades for his work and leadership, including 2014 Oregon Superintendent of the Year from the American Association of School Administrators. He also sits on numerous boards and advisory committees, including the Governor’s Council on Education and Oregon’s State Board of Education.

Grotting hails from the town of Coquille in southwestern Oregon where he a grew up in what he describes as extreme poverty. After three years in the military and more than a decade working in a sawmill in his hometown, Grotting enrolled in college in his mid-30s. Soon after, he took a job teaching elementary school in Powers, Oregon. Two years later he was invited to apply for the superintendent’s job for the small district. Since then, Grotting has served as superintendent in Nyssa and David Douglas school districts, experiences that have helped him focus on the needs of children before they enter the K-12 system.

Grotting was a key figure in the development of the Early Works initiative at Earl Boyles Elementary in Southeast Portland. Started in collaboration with Children’s Institute during Grotting’s first year as David Douglas School District superintendent in 2010, Early Works is a model for early learning and healthy development for children birth to five in an elementary school setting. At Earl Boyles, early learning programs, infant and toddler groups, parent engagement activities, and preschool support young children’s love of learning and prepares them for success when they enter kindergarten. After securing a voter-approved construction bond in 2012, Grotting prioritized construction of the Early Learning Wing and Neighborhood Center at Earl Boyles in 2014.

In this interview, Grotting reflects on his career, the importance of early learning, his goals for the Beaverton School District, and more.

Interview Highlights

[1:01] How Don’s upbringing and early life experiences and work in education have shaped his views on early childhood education.

[3:42] The importance of engaging parents to stimulate a child’s early success and connecting with Children’s Institute.

[5:44] Using a community needs assessment in the David Douglas community to better understand the needs and wants of parents and families that led to a bond approval and more supports to address the needs of children and parents: “It has been my greatest learning experience while I’ve been in education, but also has brought me the most satisfaction in making the biggest difference for kids.”

[8:35] “It truly has to be a partnership with parents. I truly believe that parents are their child’s first teacher, and until we really recognize that, appreciate it, and give it significance, we can’t help the children reach their maximum potential.”

[9:14] On how the Early Works initiative changed the learning community at Earl Boyles and integrated early learning efforts in the school environment.

[11:31] Beaverton’s school board is emphasizing early childhood education in all catchment areas.

[13:15] “Kids come to us in a lot of different ways and we have to meet each and every child where they come from and give them what they need to be successful.”

[17:50] On high-quality preschool and how to connect preschool to the K-12 system.

[20:01] Early learning as a tool for achieving education equity and close achievement gaps.

[21:25] “I’ve always said if I could do one thing, if it came down to a choice, I’d get rid of senior year of high school so we could come down and have a universal preschool.”

[21:52] Early learning as a cost saving mechanism for K-12.

[27:08] On the importance of professional development for teachers and administrators.

[28:15] Don’t forget about school boards when thinking about changing systems.

[29:50] If he could design a perfect education system to meet the needs of all kids.

[31:33] Obstacles and goals for Oregon’s next steps.

[33:17] “I truly believe it’s the key to close the achievement gap, to make a true difference for each and every child in Oregon. It will level the playing field and it has the ability to really change the economic landscape for Oregon.”

In our 20th podcast, we sat down with Ruby Takanishi, co-editor of the NASEM report

In our 20th podcast, we sat down with Ruby Takanishi, co-editor of the NASEM report

Miriam Calderon is the early learning system director of the Early Learning Division in the Oregon Department of Education. Before returning to Oregon in 2017 to lead the division, she helped build a birth-to-three system and universal preschool for the District of Columbia. She was also a senior fellow with the BUILD Initiative leading work pertaining to dual language learners and universal preschool, and served as a political appointee in the Obama administration.

Miriam Calderon is the early learning system director of the Early Learning Division in the Oregon Department of Education. Before returning to Oregon in 2017 to lead the division, she helped build a birth-to-three system and universal preschool for the District of Columbia. She was also a senior fellow with the BUILD Initiative leading work pertaining to dual language learners and universal preschool, and served as a political appointee in the Obama administration.

Many people associate school expulsion with deliberate disobedience or some form of violence by older kids in the K–12 system. But expulsion affects our youngest learners, too—preschool students as young as age 3 or 4—impacting thousands of children across the country just as their school experience is beginning.

Many people associate school expulsion with deliberate disobedience or some form of violence by older kids in the K–12 system. But expulsion affects our youngest learners, too—preschool students as young as age 3 or 4—impacting thousands of children across the country just as their school experience is beginning. Working to understand the findings,

Working to understand the findings,  Recent data confirms that disproportionate expulsions continue to grow. 2016 data

Recent data confirms that disproportionate expulsions continue to grow. 2016 data Donna Schnitker, president of the Oregon Head Start Association, adds that preschool classrooms are seeing more children with severe behavior problems each year, more children in the foster care system, and more families struggling with the effects of addiction. Ultimately, she says, kids and teachers need help. “There is always a key that unlocks the behavior or the issue, but you have to have the skills to do it,” Schnitker says. “Teachers increasingly want kids out of their class, but those kids are telling you something and they will respond if we can understand their actions and what’s behind them.”

Donna Schnitker, president of the Oregon Head Start Association, adds that preschool classrooms are seeing more children with severe behavior problems each year, more children in the foster care system, and more families struggling with the effects of addiction. Ultimately, she says, kids and teachers need help. “There is always a key that unlocks the behavior or the issue, but you have to have the skills to do it,” Schnitker says. “Teachers increasingly want kids out of their class, but those kids are telling you something and they will respond if we can understand their actions and what’s behind them.”

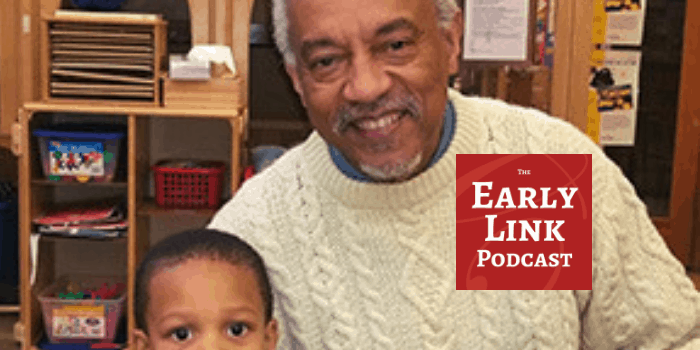

We invite you to spend an hour listening to our interview with Ron Herndon, a long-time community leader and activist in Portland and nationally. He has been the director of the Portland-based Albina Head Start since 1975, and his background includes more than four decades of advocacy efforts on behalf of low-income families and young children, and Portland’s black community.

We invite you to spend an hour listening to our interview with Ron Herndon, a long-time community leader and activist in Portland and nationally. He has been the director of the Portland-based Albina Head Start since 1975, and his background includes more than four decades of advocacy efforts on behalf of low-income families and young children, and Portland’s black community.

[31:14] The reading instruction controversy in Head Start.

[31:14] The reading instruction controversy in Head Start.