History

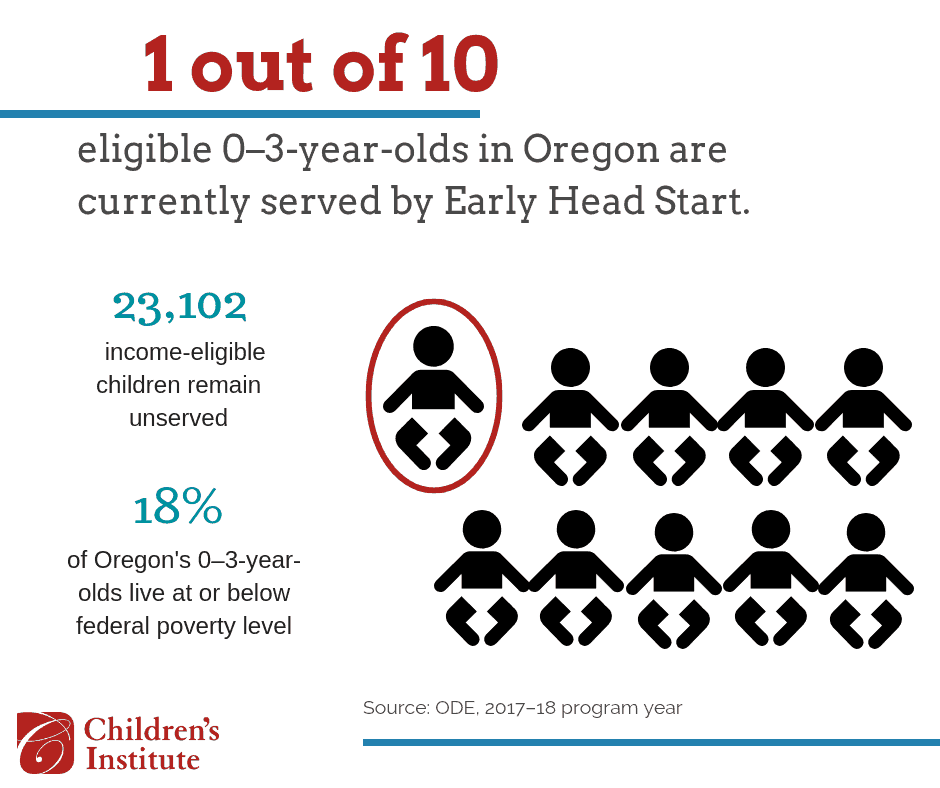

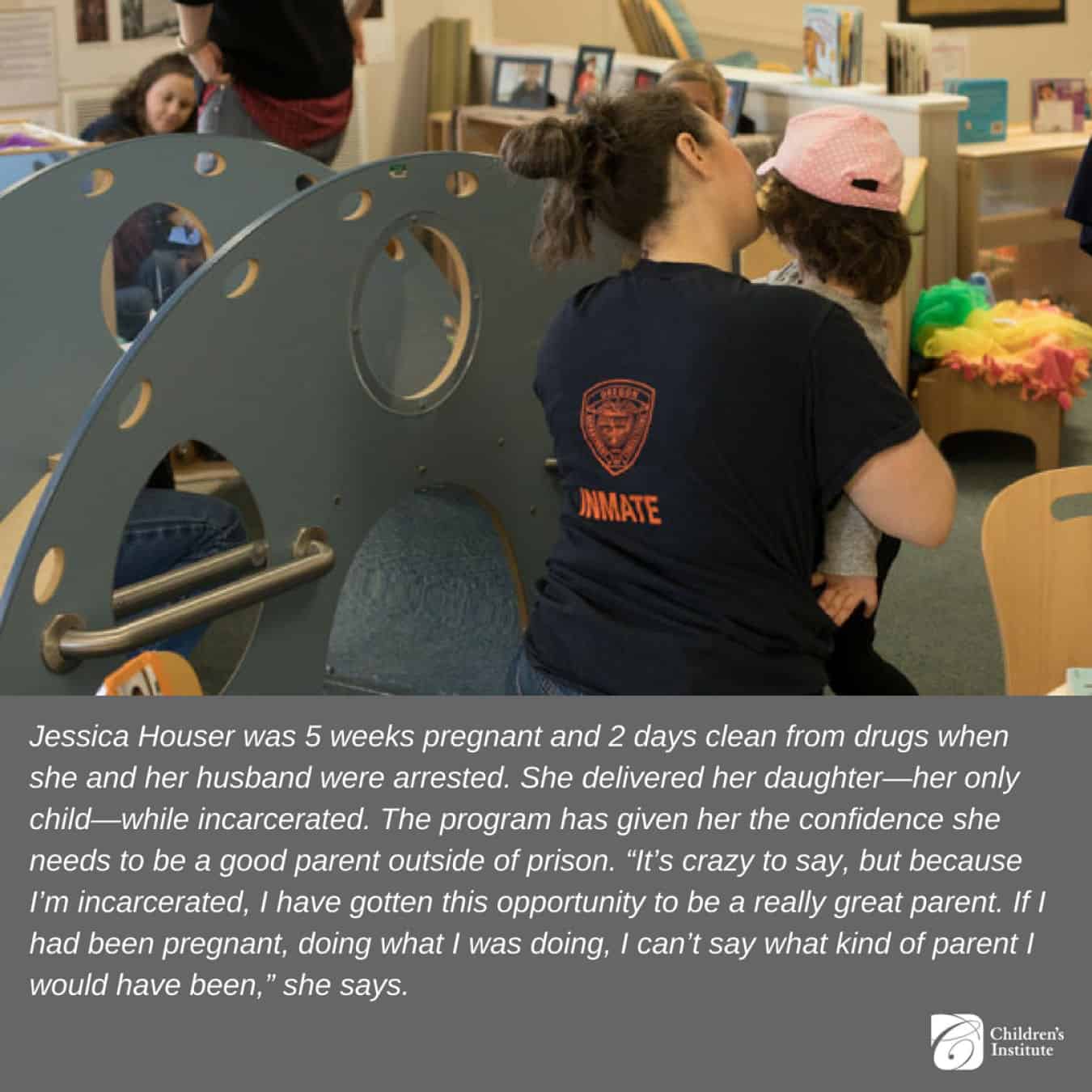

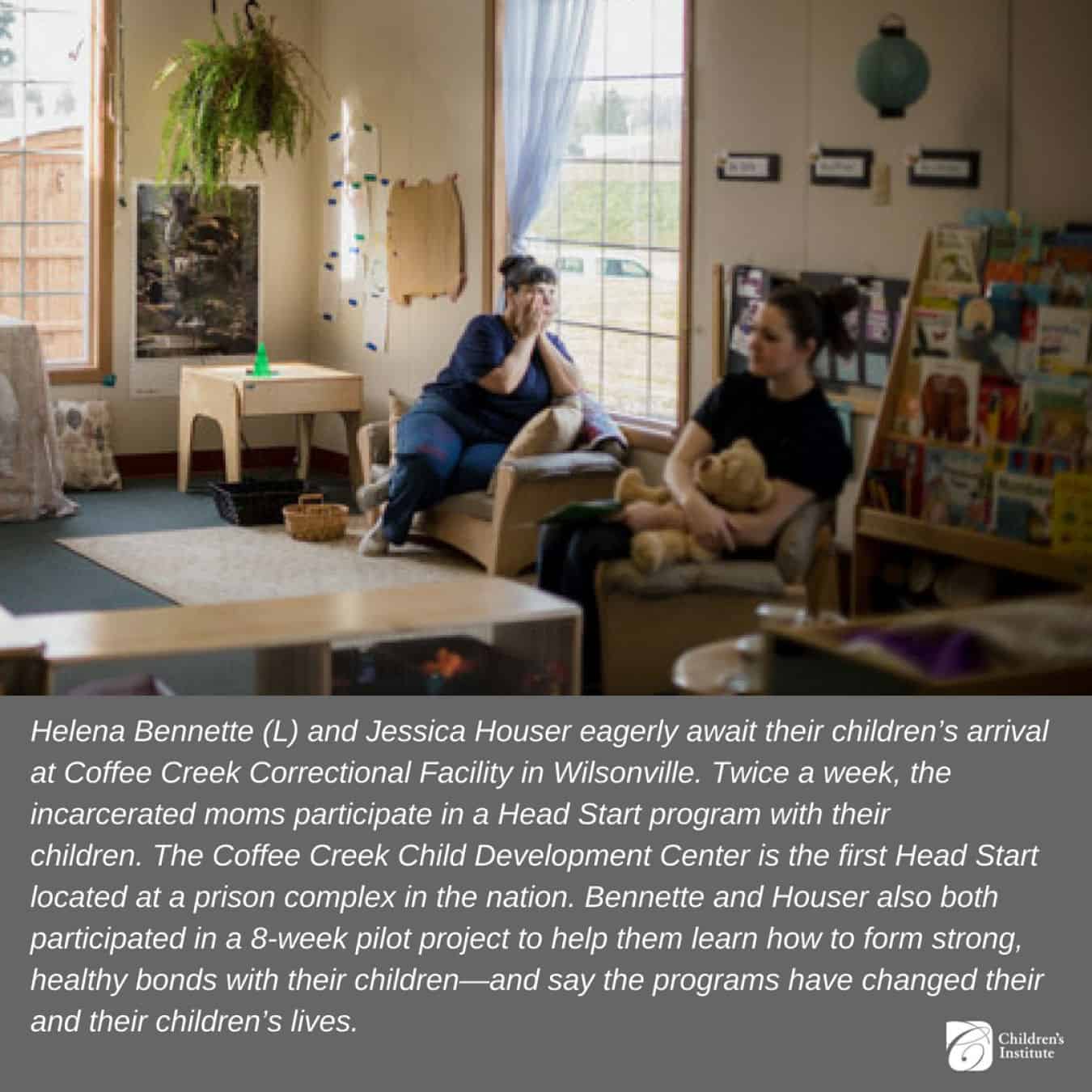

When Coffee Creek was built in 2001, the Oregon Department of Corrections partnered with Head Start to open one of the first Head Start offices co-located with a prison. Traditionally, Head Start is for children ages 3–5, and younger children attend Early Head Start. This program combines the two to allow more mothers and children to participate. The center, which is run through Community Action of Washington County, is licensed to serve up to eight children. Their mothers must be in minimum security (Coffee Creek has both medium and minimum-security areas) and have fewer than four years remaining on their sentence, Slothower says. In addition, the children must live within one hour of the prison and have a caregiver willing to drive them to and from school two days a week.

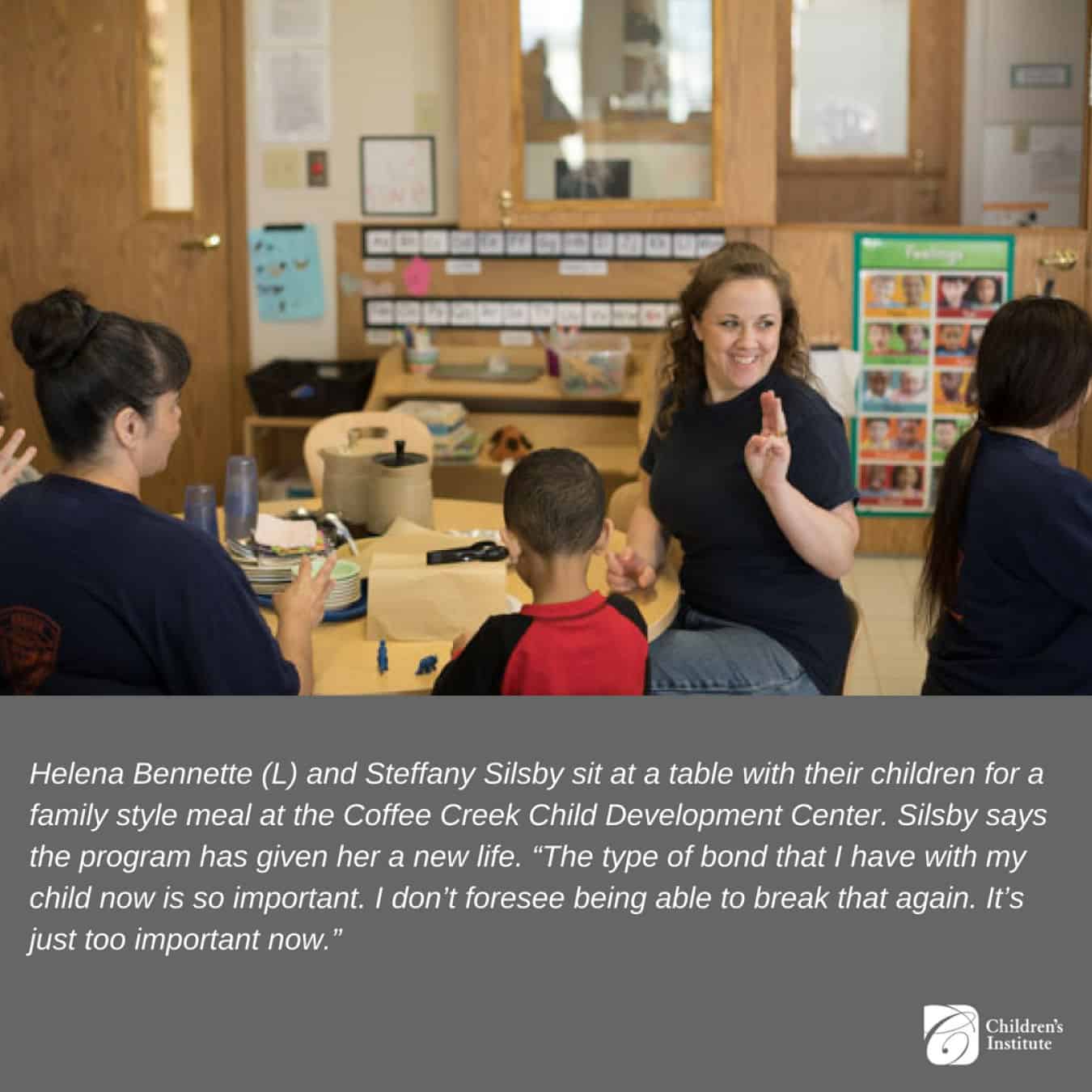

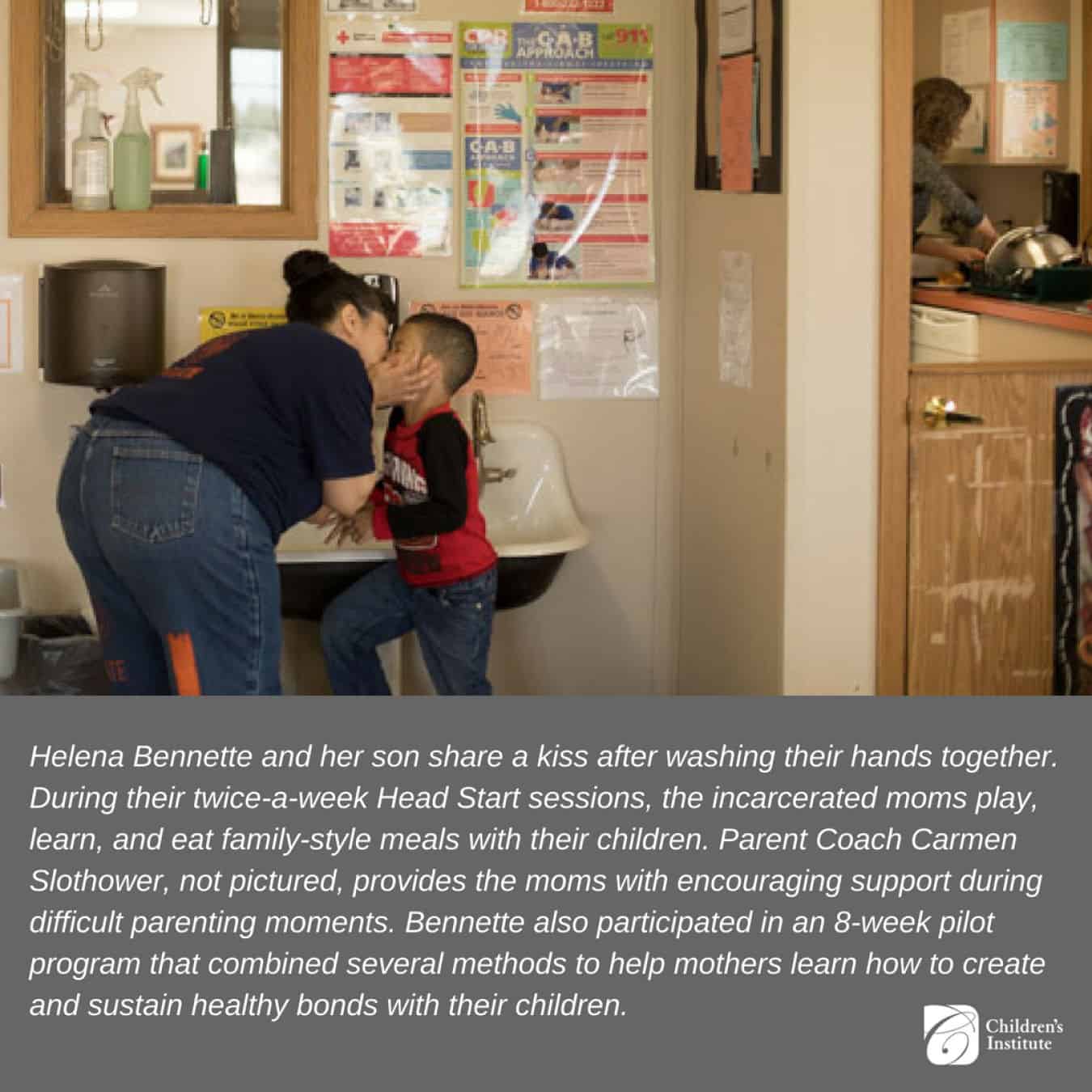

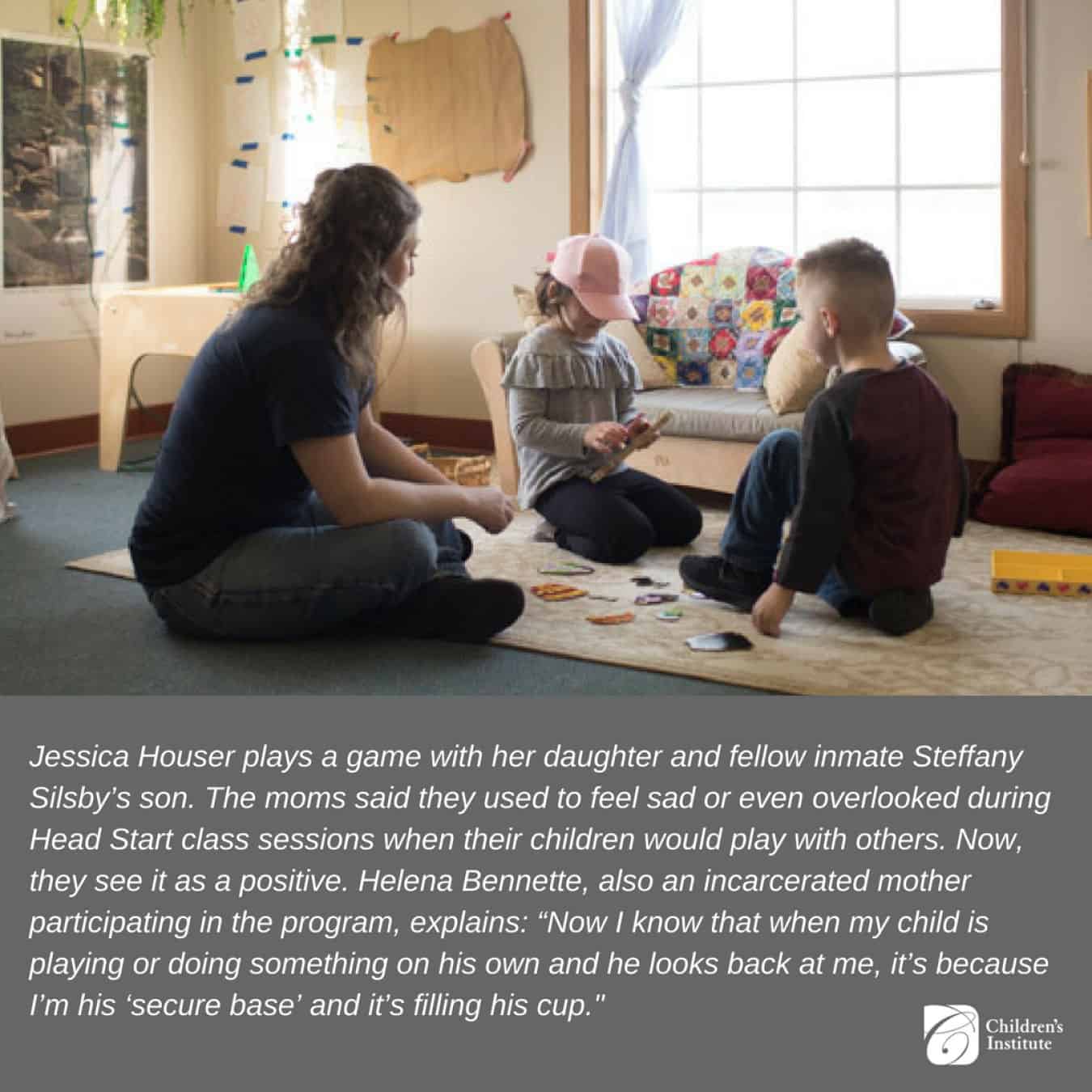

During those school days, the mothers join their children for hands-on activities, outside play and family-style meals. Slothower helps the moms navigate day-to-day challenges of parenting with practical and loving guidance, and there are two parent advocates who take turns in the classroom to provide additional support.

In 2017, Sherri Alderman, vice president of the Oregon Infant Mental Health Association and a Developmental Behavioral Pediatrician, began to develop a concept for a pilot project that would layer in additional parenting supports to help the moms build a strong, healthy bond with their children despite incarceration.

“I’ve focused my career on the most vulnerable, specifically serving very young children. I’ve done research, advocacy, systems change and workforce development all related to early childhood and attachment,” she says. Through those decades of work, she’s found models that really work—including Circle of Security. She’s also a champion of the Vroom app, which parents can download for free and receive targeted, age-appropriate ideas for ways to engage with their children.

Alderman started thinking about ways to incorporate the two vastly different—yet complementary—programs. With Circle of Security, she saw a way for the moms to dig deep and change behaviors, and with Vroom she saw a way to give parents practical tips for engagement during their regular visits.

She also wanted to layer in information particularly about phases of child development, as those times can be particularly challenging for both parent and child. “We know that unrealistic parental expectations for a child’s behavior is a risk factor for child abuse—and that can happen particularly during times of very dynamic developmental growth, such as potty training,” she says. So, she included Act Early resources through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a resource that teaches parents about developmental milestones and how those drastic changes might affect their child’s behavior.

But there were obstacles: How would she transform a phone app into something the moms, who had no access to smartphones could use? And how would she meld the three distinct programs in a way that worked together?

She worked with Circle of Security creators in Spokane and Vroom to ensure the programs were compatible. She created printouts of activities and suggestions from the Vroom app. And she worked to secure the funding to create, administer and measure the effectiveness of the pilot program.

The moms who participated continued to meet twice a week at Head Start with their kids, but also participated in a weekly two-hour group Circle of Security session where they would discuss parenting issues, talk through their problems and learn about how to promote healthy bonds with their children. In the classroom, they had posters, handouts and even key rings with Vroom materials on tiny laminated cards with ideas and pictures for positive responses to difficult situations.

Though the program finished a year ago, the moms say the intense program combined with the constant, gentle coaching from Slothower has helped them transform their ideas about parenting, attachment and themselves.

Results

“This experience has completely changed everything in my life,” says Helena Bennette, a 43-year-old mom who participated in the pilot project.

“It’s a two-way street. I can’t do what I do if you’re not hungry for information,” Slothower says. “You take the information and you’re willing to try it and run with it. I’m a firm believer in that trusting relationship,” she says.

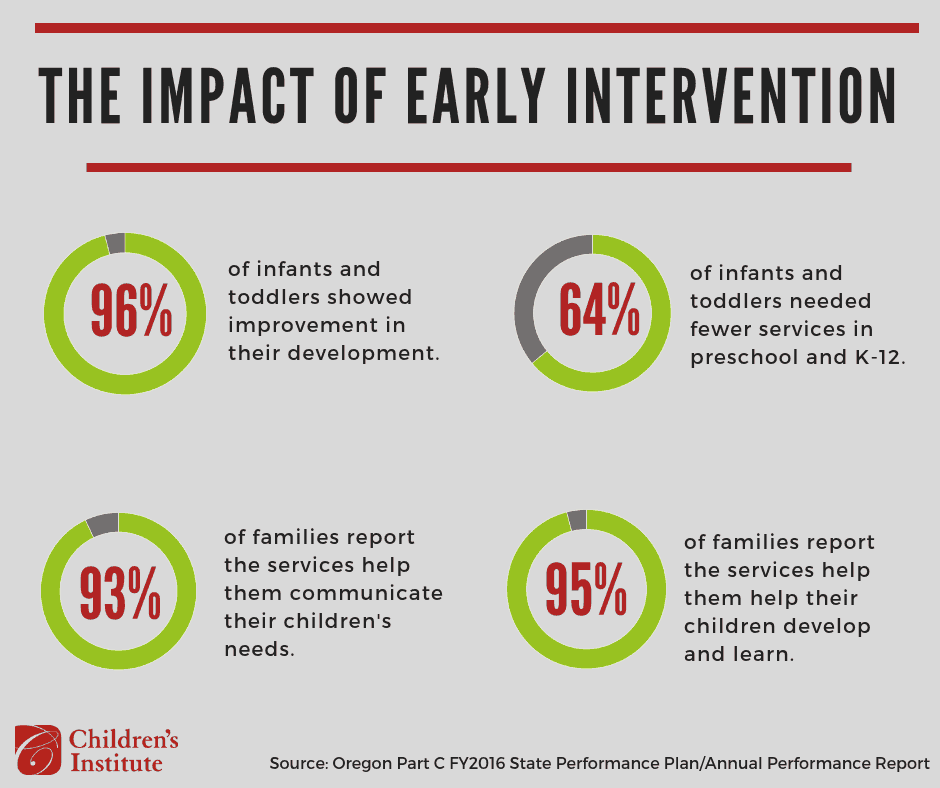

The Nurturing Healthy Attachments pilot project is finished, but Alderman says the results spoke volumes about the success of layering it in with the Head Start program. “It’s so exciting to see, first and foremost, the change that happened with the moms and their children in a two-and-a-half-month period. The evaluations supported that—there was a change.”

She says the program evaluations showed that many of the mothers in the pilot program reported that they had participated in previous parenting classes, but “Nurturing Healthy Attachments was the first one that they really felt an empathic shift,” she says, meaning the program didn’t just teach them tools and skills but actually shifted their entire mindset around parenting.

She’s working on ways the program can continue on a rolling basis to serve the needs of moms who may only be in prison for a short time. She’s also working with Coffee Creek to post Vroom activities in the prison visiting area and phone kiosks, so all incarcerated parents can benefit from the practical tips. She’s also looking at creating a program for incarcerated fathers.

“The interest and the passion is there,” she says.

Slothower says the Head Start program is working on ways to keep the moms connected once they leave the prison walls so the support continues. “We’re hoping that, as a program, we can work on ways to continue building the community and relationships when moms parole,” she says.

Cooper, the co-creator of Circle of Security, says the programs are worth every penny. “By investing in these parents now, we can reverse the cycles of incarceration and, as a society, we can reap the benefits of our efforts for generations,” he says.

To learn more about supports for incarcerated parents and programs around the country that are getting results, read our conversation with three national experts on the topic.

Results

“This experience has completely changed everything in my life,” says Helena Bennette, a 43-year-old mom who participated in the pilot project.

“It’s a two-way street. I can’t do what I do if you’re not hungry for information,” Slothower says. “You take the information and you’re willing to try it and run with it. I’m a firm believer in that trusting relationship,” she says.

The Nurturing Healthy Attachments pilot project is finished, but Alderman says the results spoke volumes about the success of layering it in with the Head Start program. “It’s so exciting to see, first and foremost, the change that happened with the moms and their children in a two-and-a-half-month period. The evaluations supported that—there was a change.”

She says the program evaluations showed that many of the mothers in the pilot program reported that they had participated in previous parenting classes, but “Nurturing Healthy Attachments was the first one that they really felt an empathic shift,” she says, meaning the program didn’t just teach them tools and skills but actually shifted their entire mindset around parenting.

She’s working on ways the program can continue on a rolling basis to serve the needs of moms who may only be in prison for a short time. She’s also working with Coffee Creek to post Vroom activities in the prison visiting area and phone kiosks, so all incarcerated parents can benefit from the practical tips. She’s also looking at creating a program for incarcerated fathers.

“The interest and the passion is there,” she says.

Slothower says the Head Start program is working on ways to keep the moms connected once they leave the prison walls so the support continues. “We’re hoping that, as a program, we can work on ways to continue building the community and relationships when moms parole,” she says.

Cooper, the co-creator of Circle of Security, says the programs are worth every penny. “By investing in these parents now, we can reverse the cycles of incarceration and, as a society, we can reap the benefits of our efforts for generations,” he says.

To learn more about supports for incarcerated parents and programs around the country that are getting results, read our conversation with three national experts on the topic.

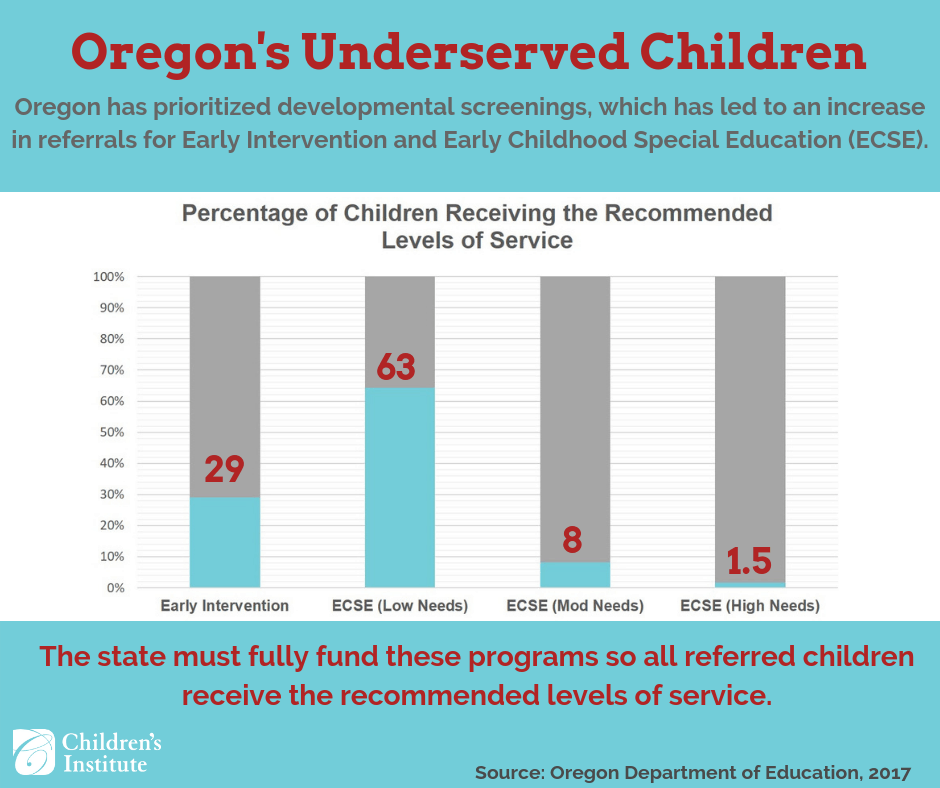

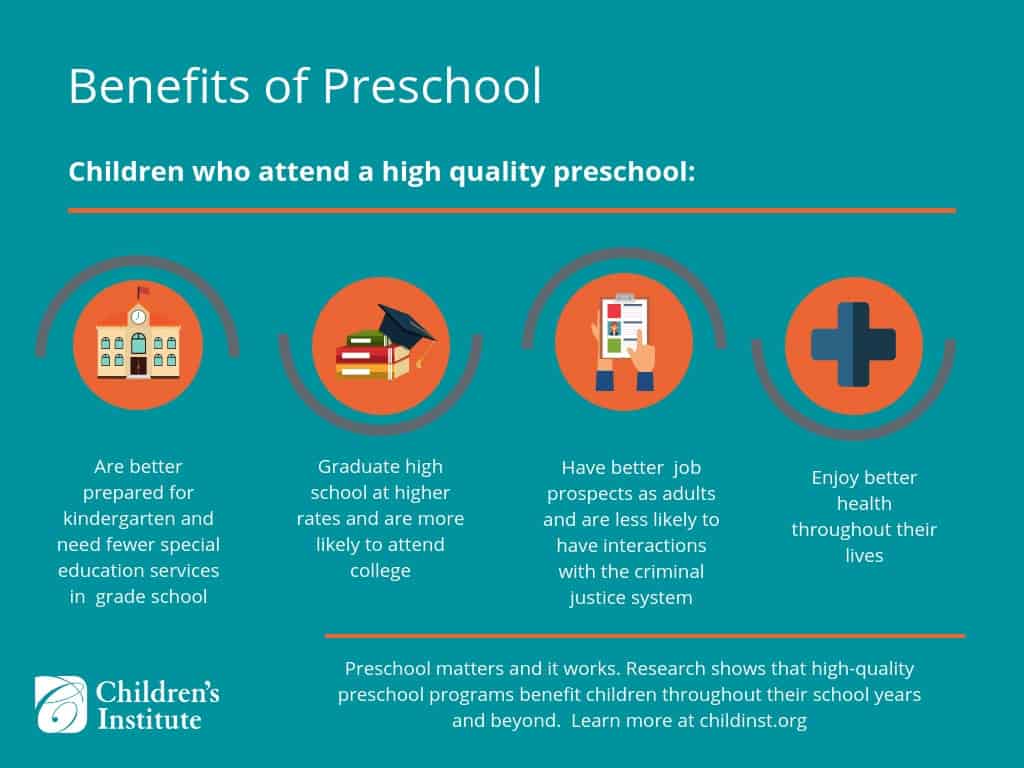

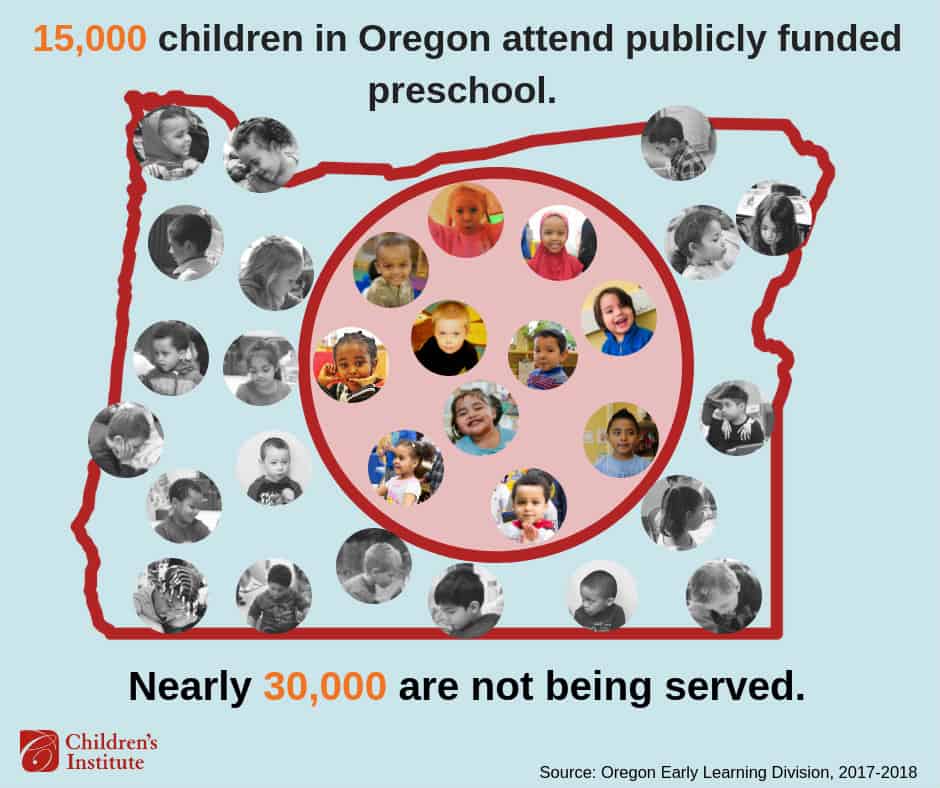

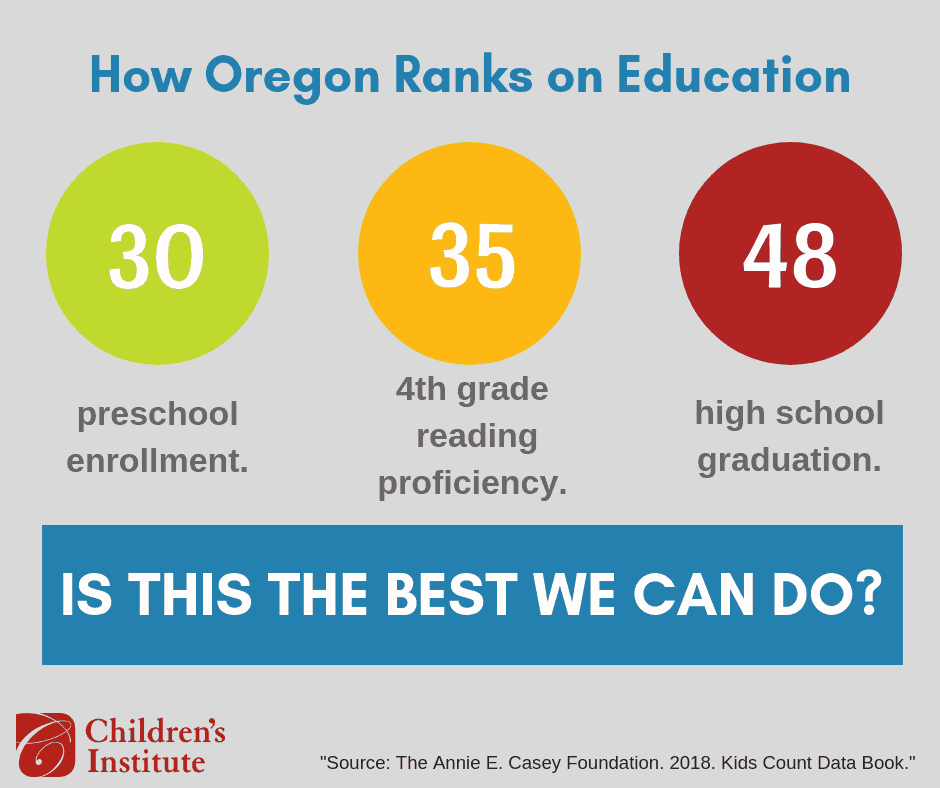

Our latest policy brief focuses on the expansion of Preschool Promise, Oregon’s high-quality preschool program that serves children and families at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty threshold.

Our latest policy brief focuses on the expansion of Preschool Promise, Oregon’s high-quality preschool program that serves children and families at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty threshold.

Donalda Dodson, MPH, RN, will receive the Richard C. Alexander Award at the Make It Your Business Luncheon on Thursday, May 18. Ms. Dodson is a pioneer in public health who has dedicated over 40 years to strengthening the health of pregnant women, young children, and families throughout Oregon. She works at the nexus of early learning and public health as the executive director of the Oregon Child Development Coalition, where she oversees the innovative Migrant and Seasonal Head Start program among eight other services. Ms. Dodson sat down to talk with Children’s Institute staff to talk about the intersection of early learning and public health, Migrant and Seasonal Head Start, and her definition of equity.

Donalda Dodson, MPH, RN, will receive the Richard C. Alexander Award at the Make It Your Business Luncheon on Thursday, May 18. Ms. Dodson is a pioneer in public health who has dedicated over 40 years to strengthening the health of pregnant women, young children, and families throughout Oregon. She works at the nexus of early learning and public health as the executive director of the Oregon Child Development Coalition, where she oversees the innovative Migrant and Seasonal Head Start program among eight other services. Ms. Dodson sat down to talk with Children’s Institute staff to talk about the intersection of early learning and public health, Migrant and Seasonal Head Start, and her definition of equity.