Scappoose, St. Helens, and Lincoln County School Districts Join Early School Success Partnership

What is ESS?

The Early School Success initiative (ESS) is Children’s Institute’s response to research which finds that children have the best outcomes when they receive developmentally appropriate, aligned instruction from preschool through the elementary grades. Developed out of the lessons we’ve learned through Early Works, ESS is a partnership. ESS partner districts are provided with consultation, professional development, and coaching to help them strengthen and align preschool and elementary learning experiences and develop deeper, more effective partnerships with families.

Though most education reform efforts and professional learning opportunities for educators focus on grades 3–12, we know that changing student outcomes and closing opportunity gaps requires a transformational shift in how we think about and approach education in the early years. The state of Oregon recognizes that “the greatest gains are achieved when the services and instruction children receive are well aligned and structured to build on one another.” ESS exists to support educators and communities to make this valuable alignment possible.

ESS Expands to Include Rural Districts

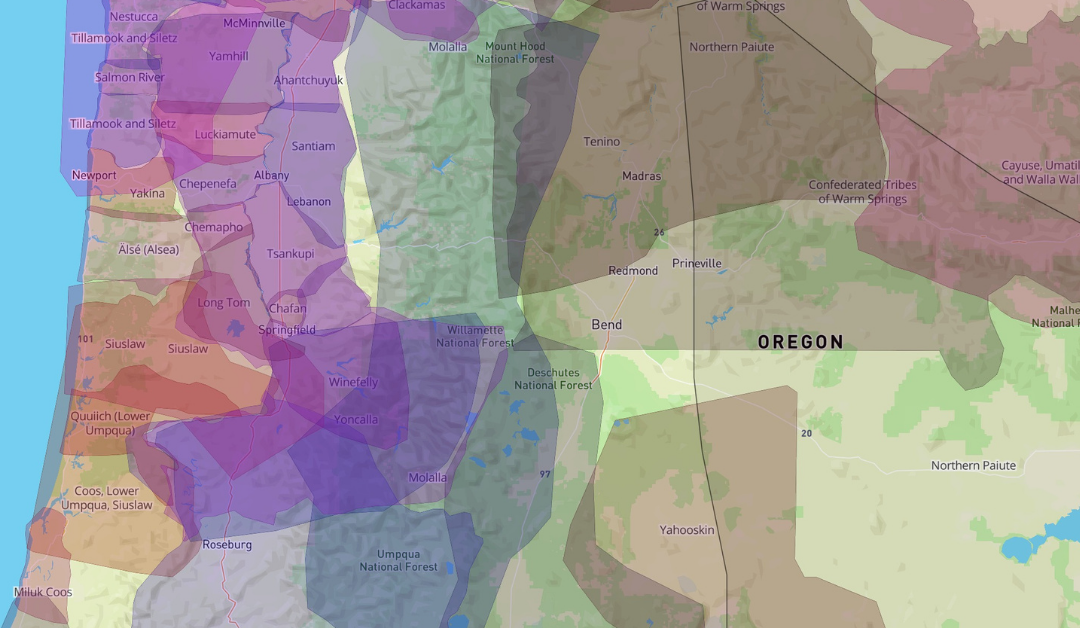

ESS launched in 2019 with Beaverton and Forest Grove School Districts as its first partners. As these two districts enter their third year, CI has sought to expand the program. We’re pleased to announce that we will be working with Lincoln County, St. Helens, and Scappoose School Districts to bring ESS work into Oregon’s rural context.

Through a rigorous application process that included input from district leadership, teachers, parents, and other members of the school communities, these district partners were chosen based on demonstrated commitment to early learning, the value of partnership, and existing work toward racial equity.

“With the vision that all young children and their families will thrive, the Scappoose and St. Helens School Districts are thrilled to be able to build upon the early childhood landscapes within our communities,” says Jen Stearns, director of student achievement for Scappoose SD. “Our partnership with Children’s Institute and the Early School Success Grant will empower us to serve more students effectively, encourage parent engagement, and support the alignment of dynamic instruction from preschool through 2nd grade. This is an exciting time to be serving the students and families in Columbia County.”

Dr. Katie Barrett, director of elementary education at Lincoln County SD said, “Our district is immensely pleased to have the opportunity to work with Children’s Institute on the Early School Success project. We recognize the need and importance of aligning our early learning program with our elementary program, and this grant will allow us to continue to strengthen this alignment as we build sustainable systems and structures that can be replicated in all four areas of our district. We are grateful for the recognition of the work we have begun here in Lincoln County School District, and look forward to our partnership with Children’s Institute.”

Related Links

Beyond Fadeout: Why Preschool to Elementary Alignment Matters