Inclusive Early Education for All Children

Summary

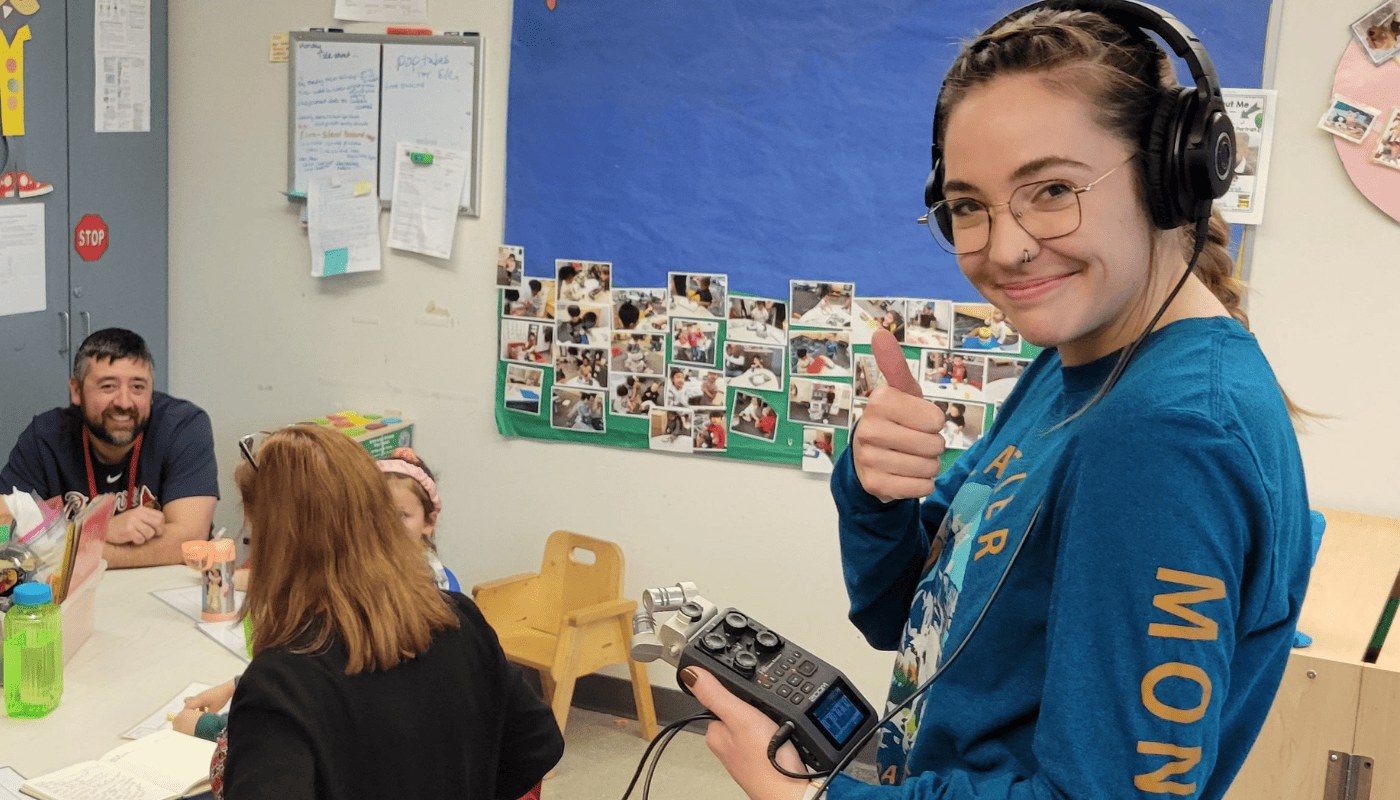

In this episode of The Early Link Podcast, host Rafael Otto sits down with Liane Chappell, at the Hillsboro Early Childhood Center in Hillsboro, Oregon, to talk about Early Intervention and Early Childhood Special Education. Chappell is the principal at the Early Childhood Center, located at the Northwest Regional Education Service District (NWRESD).

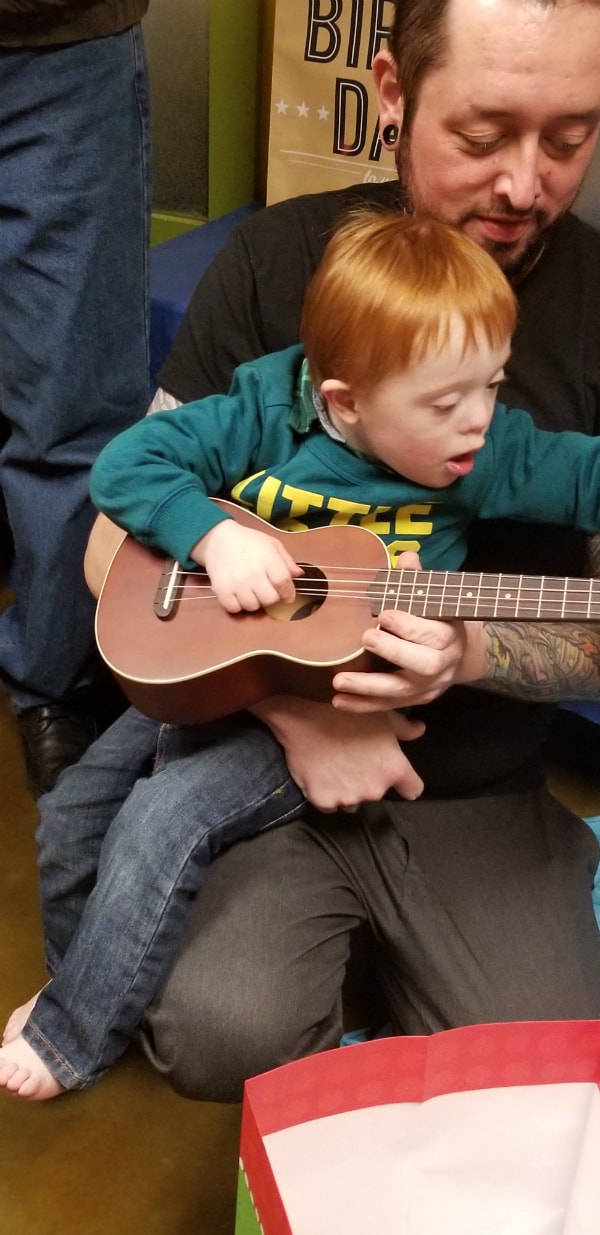

The goal of the Early Childhood Center is to serve kids who have delays and disabilities, and to help them make progress in the areas where they need support. Notably, their aim is to serve every child in an inclusive, natural environment – whether that’s at home, in the classroom, or running errands with their family.

“I’ve always had a passion for inclusion and for wanting to see kids with disabilities be a part of their community like every other kid,” said Chappell. “That’s what has driven me throughout my time at NWRESD and even prior to that in early childhood. I’m working to see every kid be included and get the opportunities that they deserve.”

We think you’ll want to hear the rest of Liane’s story. Listen now!

More about The Early Link Podcast

The Early Link Podcast highlights national, regional, and local voices working in early childhood education and the nonprofit sector. The podcast is written, hosted, and produced by Rafael Otto, Children’s Institute’s director of communications.