Melissa Tyler of Ontario, Ore., worries about sending her 5-year-old son into school this fall during a pandemic. But she’s even more concerned about Mason, who has Down’s syndrome, slipping behind.

“I think socially he could be losing ground; that is my biggest concern,” says Tyler, a bank teller in the town on Oregon’s eastern border. “He thrives in a classroom. He needs that social interaction. He hasn’t gotten it since March.”

Candice and Adolfo Jimenez have enrolled their daughter, Xitlalli (pronounced seet-lolli), 4, and son, Necalli, 10, in a Spanish immersion program at the private International School in Portland. They know their kids will get a pared-down version of their education through distance learning, but they prefer that over exposing their children to COVID-19.

“We feel most comfortable with being virtual because it provides safety in a time of uncertainty,” says Candice Jimenez, research manager for the Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board.

Parents of Oregon’s youngest students express varying views on how best to resume education this fall. They all must weigh the risk of infection against the risk of their children losing ground at a critical time in their early education.

“Some folks want to go back into the brick-and-mortar no matter what,” says Don Grotting, superintendent of Beaverton School District. “Others say, ‘Until there is a vaccine, we are not sending our kids to school.’”

And parents who work outside their homes must find a place for their kids at a time when child care has become even scarcer than it was before the pandemic.

“Even if I can afford child care,” says Grotting, “where are those places going to be?”

Learning at a distance

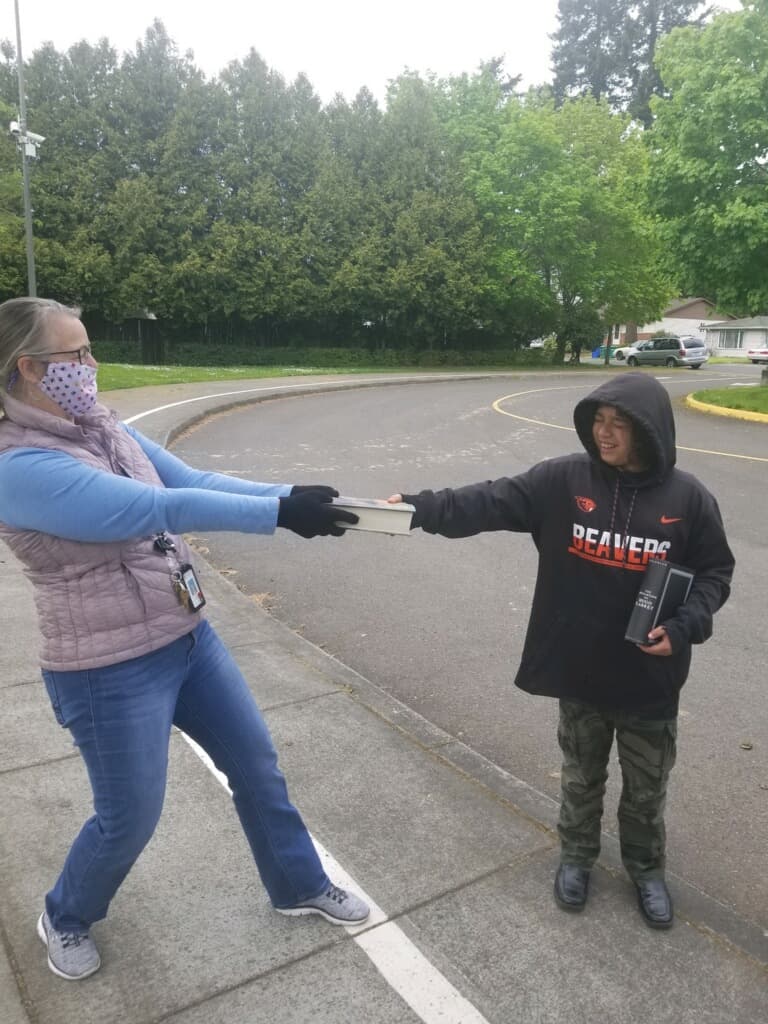

Beaverton, like Portland, North Clackamas, Tigard-Tualatin, Salem-Keizer and other large districts, will open virtually at least through mid-November. Gov. Kate Brown has declared schools cannot open classrooms to students until statewide and county COVID-19 metrics meet certain criteria for three weeks in a row. With the positive virus rate still above 5 percent in mid-August, all public schools will open with only distance learning.

There could be exceptions. “Subsets of schools” in smaller communities, state guidelines say, will be allowed to return to in-person instruction based on the local level of virus spread, prior to county and state metrics being met. This guidance also makes allowances for limited in-person instruction for groups of students K-3 students, English learners, and students experiencing disability. These allowances, however, are not mandates. Schools and districts are expected to offer in-person provisions for priority populations “to the extent possible,” as determined at the local level.

State and district leaders are doing research and working to build educators collective capacity around what works best in providing distance education to young students, says Jennifer Patterson, the state’s assistant superintendent for the Office of Teaching, Learning and Assessment. They want to balance virtual teaching with applied learning, where children engage in off-screen projects and activities with learning objectives, she says.

The state also is encouraging teachers to help households exploit their assets, says Patterson. If they have extended families living nearby, for example, they could tap siblings, grandparents and other relatives to help teach young children with the help of online teachers. They could use games, play, songs and projects to help young children build skills in literacy, numeracy and vocabulary, Patterson says.

The Jimenezes say they are fortunate to both be working at home so they can trade off helping their children with online education. They worry more about their children’s social and emotional development and its relation to their academic growth, Candice says.

“You want to keep having that social system for them so they are getting to know other kids,” she says. “I worry about their social and cognitive development in relation to other kids in the community.”

Other parents worry their young children will lose academic ground at a time when the quality of their education can dramatically affect the trajectory of their lives.

Dove Spector, Clackamas, a colleague of Candice Jimenez and project specialist for the Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board, and her husband, Kyle Dexter, a screen printer, have enrolled their 4-year-old son in the Portland Parks Preschool. They worry their child is going to miss critical socialization because the school is opening remotely.

“I worry about giving him the proper tools to be successful academically,” says Spector, a Nez Perce tribal member. “It really stems from my own experience with racism in the education system.”

Learning in the classroom

Whenever schools do physically open their buildings to children, most parents clearly want them to do so with an abundance of caution. The Oregon Department of Education’s Early Learning Division surveyed 3,060 parents in need of child care, including preschool. The parents collectively had 1,139 children two or under, 1,955 children ages 3 to 5 and 890 kids ages 6 or older.

About one in five parents were uncomfortable with their children receiving meals prepared by staff, more than half were uneasy with their children going to public parks or using public play equipment and two thirds were nervous about their children going on field trips.

In the small district of Yoncalla 45 miles south of Eugene, nearly nine in 10 parents want to see their children back in school this fall, says Superintendent Brian Berry. Parents are heavily involved in plans for health and safety measures that meet state guidelines.

“I feel like we can do this and still have our kids in school,” says Mary King of Yoncalla. Her 4-year-old daughter, Rosemary, will be in the district’s preschool, created in partnership with the Children’ Institute’s Early Works program. “I have faith in my school district and in the preschool that the cleaning precautions will be increased.”

The parents felt strongly that schools and child care providers:

- Require staff and children with COVID-19-like symptoms to stay home.

- Follow all Oregon Health Authority sanitation and clearing guidelines.

- Have a plan in place to communicate with families about COVID-19 issues such as infections, policy changes and contact tracing.

- Have flexible staff sick-leave policies for cases of sickness or virus exposure.

- Require children and staff to wash their hands for 20 seconds frequently throughout the day.

- Check all children and adults entering the building for fever and virus symptoms.

Scarce child care

Some parents, including a disproportionate share with low-income jobs, must work outside the home and find care for their young children while they do so. Yet they often cannot afford child care, which averaged about $1,200 a month before the pandemic. What’s more, the state’s licensed child care capacity has been cut by more than half, from 106,000 slots a year ago to 48,000 today. The state’s child care guidelines allow only emergency child care providers who give priority to children of first responders, health care workers and other essential personnel to operate. The state has, since May, awarded $22 million in federal coronavirus relief to about 2,800 child care facilities. That’s far fewer than the 3,787 providers operating in January, and, under state health guidelines, most centers still functioning must do so with fewer children than before the pandemic.

While K-12 public schools, along with government-funded preschool programs like Oregon Pre-K and Preschool Promise, have responded to health and safety guidelines by closing for in-person learning, they continue to receive funding and will remain intact through the crisis, retaining their workforce and continuing to provide virtual learning opportunities to students. The vast majority of child care programs are not in the same boat. Because 70 percent of child care and preschool funding comes from parent tuition, which is only paid when a child is able to attend, providers who have had to close or who are operating at a decreased capacity, without comparably decreased overhead, face enormous financial hardship and may be forced to close permanently, with impacts to the availability of child care lasting long into the future.

Tyler of Ontario, a single mother, has been able to rely on her nearby parents to watch Mason while she works at a bank. She doesn’t know what she would do without their help, she says, as she cannot afford child care. Plus she would have a hard time finding it. With less than one child care slot for every three children, her Malheur County already qualified as a child care desert before the pandemic hit. Now there are even fewer seats. By late summer, the 9,930-square-mile county had only 10 vacant school-age child care slots.

As of mid-August, the statewide capacity for child care for all ages stood at 47,622 children with 12,495 vacancies. Even at capacity, the state has enough child care slots for only 10 percent of its 467,000 children ages 9 and under.

With child care so scarce and expensive, parents like Tyler are turning to relatives or friends to watch their children. Others are quitting their jobs or hiring nannies. And some parents are grouping in bubbles so they can take turns babysitting or share costs for tutors.

Some local governments are looking for ways to provide more child care services, but as with so much in this pandemic, the majority of Oregon parents will be on their own.

Of course, what all parents want is a return to normal school, says Kayla Bell, Beaverton School District’s administrator for elementary curriculum, instruction, and assessment.

“We understand that,” she says.

Spector, of Clackamas, says she’s grateful she can work at home and help her son with his distance learning, but she worries about his future.

“It just feels like [the pandemic] is never going to end because of a lack of federal leadership,” she says. “I’m happy to do my part, but I’m frustrated. It’s hard not to feel that this is going to have a strong impact on my son as he grows into adulthood.”