Parents, Educators Call for “More Time, More Hours” to Improve Early Special Education Outcomes

The transition to kindergarten is tough for a lot of kids, but for those with developmental delays and disabilities, it can be especially challenging.

Tristan Davis, who was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder through Early Intervention (EI) services offered by the Clackamas Educational Service District, was primarily non-verbal when he began preschool at Sunset Primary’s Early Childhood Special Education (ECSE) classroom.

His mom Tracey described preschool-aged Tristan as a happy boy who struggled with regulation and anxiety. Looking back, Tracey says she was nervous as Tristan began preparing for the transition to kindergarten as his ECSE preschool class met for only two and half hours each day, a few days a week.

She compared that to the experience of her older son, Anthony, who attended a traditional preschool program for five hours a day, 3–4 days a week.

“[Tristan’s] teacher, Eric, was amazing with him, but I noticed there was not a lot of consistency with the aides who were there. They seemed to have more children than help, sometimes. There were children all across the board developmentally.”

Tracey, who later became a special education paraeducator, is frank about the reality of EI/ECSE services given current funding levels, including the impact that pay and other workforce issues have on the special education field.

“Eric does it because he loves it and he’s great at it. But he was definitely not paid what he should have been.”

When asked what might have made more of a difference for Tristan as he transitioned to kindergarten, Tracey said, “More time, more hours.”

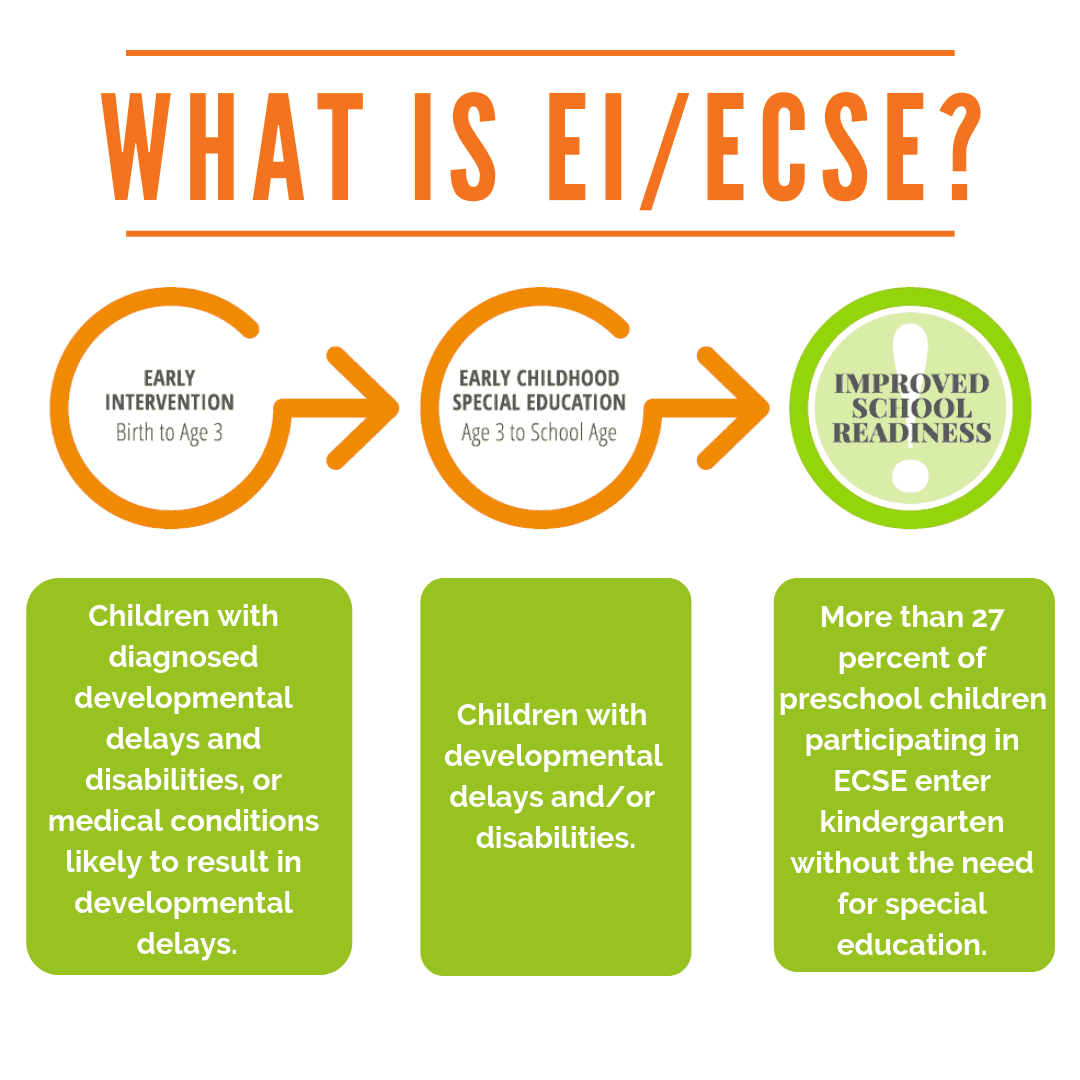

EI/ECSE Saves Taxpayer Dollars, But Is Still Underfunded

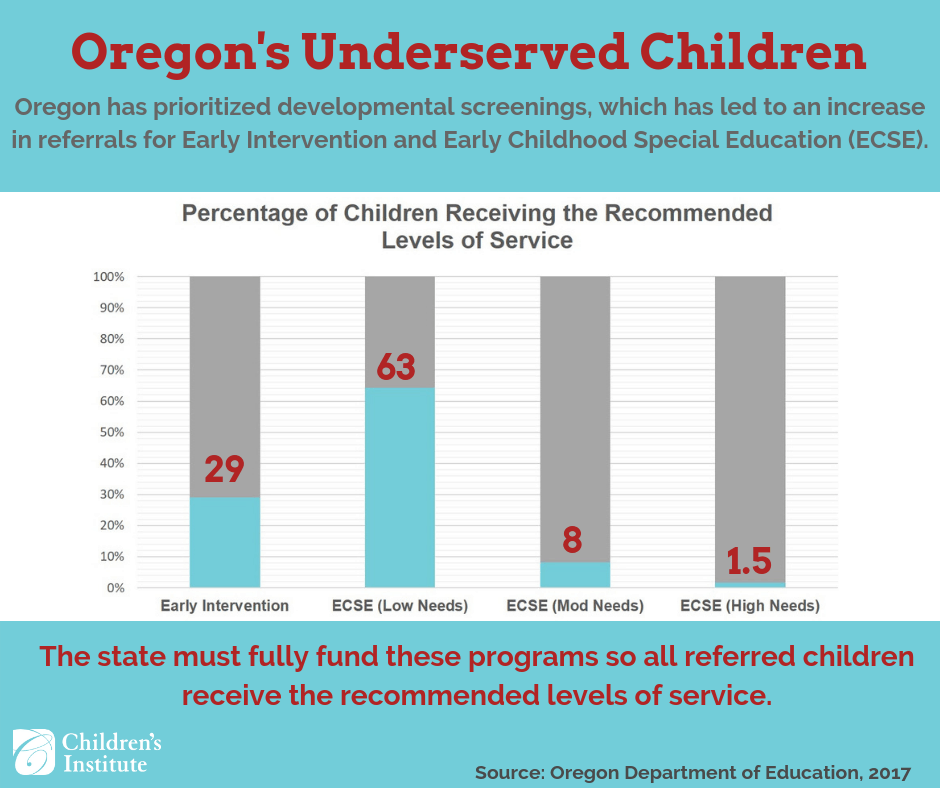

Tracey’s recollection of the stretched resources in her son’s classroom echoes reports from Children’s Institute and others that shows most children in EI/ECSE programs are not being served at recommended levels.

According to state data, only 28 percent of children enrolled in EI programming receive the recommended level of service. On average, children enrolled in ECSE with high needs only receive 8.7 hours of preschool per week, rather than the recommended 15 hours per week. EI service levels have actually decreased by an average of 70 percent from 2004 to 2016.

The governor’s latest budget proposal devotes $45.6 million to EI/ECSE, about $30 million less than what the Early Childhood Coalition and the Alliance for Early Intervention says is needed to adequately serve children. In the 2014–15 school year, more than 21 percent of children exiting EI had caught up with their peers and did not require ECSE services, saving the state nearly $4 million annually.

Those who work in the field see the need firsthand. Carla Moody Starr, a speech language pathologist on the EI/ECSE evaluation team at the Northwest Regional Educational Service District, says EI/ECSE evaluation staff are often the first point of contact for families who may be overwhelmed, in shock, or in a state of grief if their child is significantly delayed.

“We take into consideration family and child trauma, socio-economic differences, language, and cultural differences— being sensitive to parents, but also educating and advocating for their child is an art. More service is needed for kids with developmental or communication delays before kindergarten. More service is needed for family coaching and education as well. Without adequate EI/ECSE service, these children with disabilities may not develop the skills they need to be successful once they enter elementary school.”

Despite insufficient funding for EI/ECSE services, Tracey has high praise for the West Linn-Wilsonville school district’s ability to provide a wide array of resources to support her son’s learning and development.

In advance of his kindergarten school year, Tracey met with the staff at Trillium Creek Primary School to map out an Individualized Education Plan (IEP).

“Before school started, his kindergarten teacher left Tristan this long [voicemail] message saying, ‘I know you can’t talk to me, but I want you to know I’m so excited to see you.’ It meant so much to him and so much to me.

“I was so lucky with West Linn. My rent is outrageous and I’m a single mom, but I really felt there was never a question of—does he really need this? His teacher noticed he liked to jump and they got him an indoor trampoline, just in case he needed to jump it out. They just want him to be successful. That’s the community they foster there.”

EI/ECSE Supports Broader Inclusion Efforts

West-Linn Wilsonville is considered a full-inclusion district, meaning both neurotypical children and children with special education needs are taught in the same classroom. While the Oregon Department of Education sets a state target of 73 percent of special education students being served in a general education classroom, West-Linn Wilsonville far exceeds that standard, reporting that 85.7 percent of its special education students are served in that setting.

Tristan is now a third grader at Trillium Creek Primary and Tracey reports that he’s doing well. “He loves school and has many friends that he loves. He still has hard days and struggles with anxiety. Overall, school has been a positive experience for him. His team is always communicating with me, and I feel they are invested in his success and happiness.”

Benefits For Typically Developing Peers

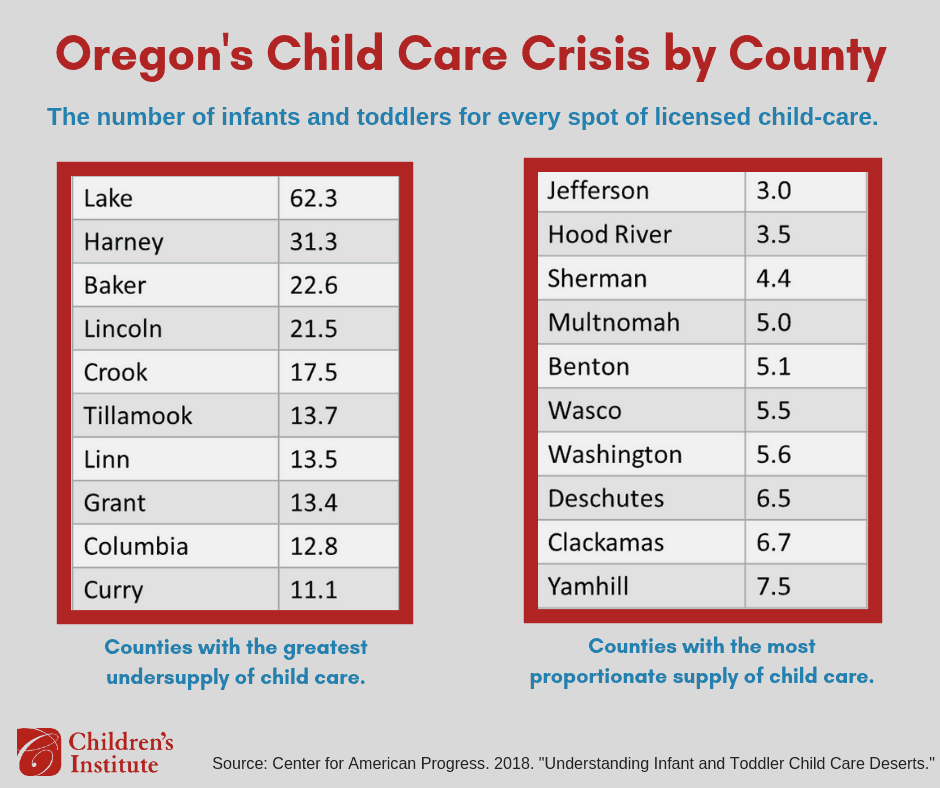

Ginny Scelza is a parent of two children who attended the Multnomah Early Childhood Program (MECP), operated by the David Douglas School District. The program runs preschool classes at 11 locations across six school districts and offers an inclusive environment where children with special education needs learn alongside typically developing children.

Ginny, whose son and daughter are typically developing admits that her interest in the program was due to the affordable cost and convenient location, initially just a few minutes from her home. MECP tuition costs $32 a month for a twice-a-week program, much less than private preschool programs in the area. Free and reduced tuition is available for qualifying families.

“The fact that the preschool was in the same building that [my son] would be in for kindergarten was a big draw—that made so much sense.”

Ginny also valued the program’s emphasis on social emotional development.

“I saw [preschool] as a transition from the home environment to a classroom community. How do you share? How do you develop friendships? How do you work as part of a team? Having my kids in the program helped strengthen their empathy for other people and that was more important to me than academics.”

Ginny credits the program for creating a smooth transition to kindergarten for both her children. She also notes that the benefits of such programs have a positive effect that goes beyond just those children who have disabilities and delays.

“At age 3 or 4, [my daughter] was learning that kids who were in wheelchairs or needed extra help—they were also a part of her school community. It was normal. How does that not become part of who you are?”

Learn More and Support Increased Funding for EI/ECSE Services

Oregon Must Invest More in Young Children With Disabilities: A Conversation With FACT Oregon’s Executive Director

Join us and a growing coalition of Early Childhood advocates in requesting an addition $75 million investment to increase service levels for children with disabilities and delays.