Supporting a Strong Start for Children with Disabilities

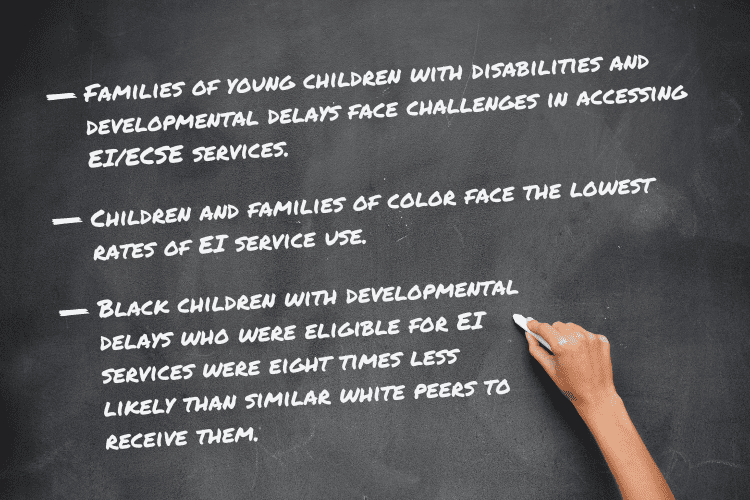

We often talk about how investing in a child’s earliest years can set them up for long-term success. In a child’s first few years of life, more than one million new connections in the brain are formed every second, creating a foundation for the connections that form later. In order to build a strong foundation during this period of rapid brain development, it’s important to connect families with the tools needed to support their child’s development as early as possible.

New America’s newly launched blog series will examine early intervention and early childhood special education throughout the coming year.

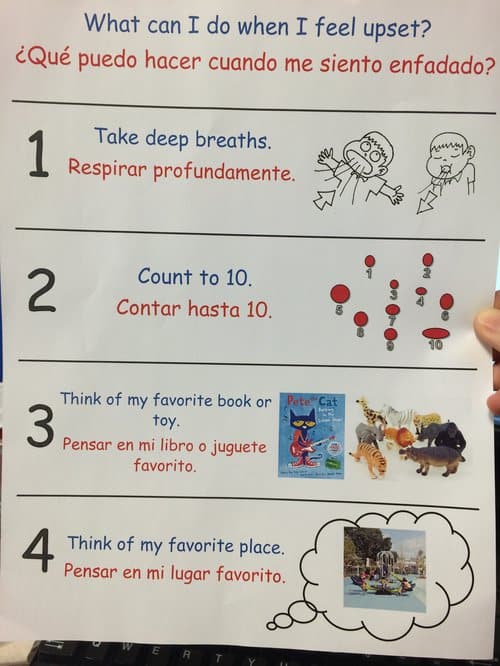

Early intervention (EI) is a set of services available to families with young children. These range from physical therapy and occupational therapy to nutrition and speech and language services. Specifically, under Part C of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), children from birth through age two with developmental delays or disabilities or who are at risk of having a developmental delay are entitled to EI services. In pre-kindergarten settings, these services are often referred to as early childhood special education (ECSE) and are administered under IDEA Part B Section 619 (see graphic below).

New America

Children’s Institute

One reason for these challenges may be the shortage of EI service providers (think speech and language pathologists, physical therapists, occupational therapists) who are trained to conduct evaluations and provide services. In a 2022 survey conducted by the IDEA Infant and Toddler Coordinators Association, all 45 state respondents reported provider shortages, with more than 80 percent experiencing shortages of speech and language pathologists and physical therapists. This theme came up in roundtable discussions we held earlier this year with 19 stakeholders* working at the intersection of disability and early childhood across the United States. The roundtable participants—which included EI providers, pediatricians, service coordinators, state Part C coordinators, and researchers—discussed how the current workforce crisis impacts families’ experiences navigating the referral and evaluation process, such as long waitlists for appointments and whether their concerns about their child’s development are taken seriously. The participants noted how addressing staffing shortages must be done in tandem with efforts to improve the cultural, linguistic, and racial diversity of the EI workforce. Participants also suggested expanding reflective supervision to support staff retention.

Funding was another theme that came up during the roundtables. Currently, funding dictates how many children receive access to EI—from the frequency, duration, and location to whether the service is available at all. Participants emphasized how the opposite should be the goal: a reality where service delivery—or the number of children eligible for and receiving services—is not constrained by the amount of funding that is invested. Participants touched on the need to fund proactively toward long-term, systems-building components, such as community health workers to support families navigating care and services for their children or ongoing training for service providers in all settings (e.g. district, state-contracted agency, private practice).

While participants were eager to discuss the challenges, there was an even stronger desire to focus on solutions. State leaders meet often with local practitioners and have gained a keen sense through the years of how these issues impact EI service providers and families in their state. Roundtable participants were largely in agreement over the major issues facing young children with disabilities and their families. However, there remains a gap between awareness and action, and participants wondered what state and federal policy levers could be valuable in meeting the mandate of IDEA Part C and ensuring equal protection under the law.

Shutterstock/New America

In our ongoing examination of meeting the educational needs of young children with disabilities and developmental delays, we are excited to launch an ongoing blog series in 2024 where we plan to tackle several questions, such as: What can states do to make EI and ECSE more equitable for children of color and children from families with low incomes? How can policymakers address challenges in meaningful ways? How can we better connect awareness to action? The series will address themes from the roundtable and include recent research.

If early childhood systems are to be designed to meet the needs of all children and families, EI and ECSE need to be recognized as key parts of that system. You can find New America’s growing body of work focused on disability policy on our disability resource page.

*For the roundtables, we were intentional about having representation across states, political contexts, and communities, but we acknowledge that these participants’ perspectives represent only a subset of those working to improve access and outcomes for young children with disabilities.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY 4.0). It is attributed to Carrie Gillispie and Nicole Hsu. The original version can be found here.