More than two dozen education, health, and community leaders met in October to begin mapping out the future for Baker City’s youngest citizens.

Early childhood advocates in Baker City, a frontier Oregon town with a population of 10,000, were hopeful that passage of school bond measure I-88 would fund the transformation of Brooklyn Primary School into a dedicated early learning center.

The renovation was one of a number of facility updates and additions that supporters argued were needed to better address the modern safety, security, and programming needs for Baker students. In addition to the early learning center serving students and families from birth to kindergarten, planners wanted to build a new school for grades 1–6.

Baker had not passed a school bond since 1948, when voters committed funding to build four new schools, including Brooklyn Primary, completed in 1955. Brooklyn, now operating as K–3 school, is overcrowded with 465 students in a school built for 348. Last week, residents voted the measure down by a more than two to one margin.

Creative Problem Solving to Meet Student Needs

Brooklyn Primary Principal Phil Anderson is doing his best with limited resources and working creatively to meet the needs of 21st century students within the structure of a building created for an earlier generation.

The school counselor works out of the old shower room and P.E. and meal services operate out of a shared space, with students weaving in and out on a carefully choreographed schedule. Music classes, a behavior-focused classroom, and health services are all provided in modular classrooms located outside the school.

When asked about the space challenges, Anderson focuses on the positive. “We believe in every child and we are committed to educating and inspiring all children to their highest level of learning…our building does limit the potential of current instructional practices, but it never limits what we believe our students are capable of.”

Baker City is one of 68 school districts in Oregon that operate on a four-day school week. For students who need more academic support, meals or other services, there is Friday Academy—a district-wide K–12 program. Witty notes that Friday Academy exists because, “We have an opportunity gap. And as we close them, we help every kid in our system. The question is, how do we get services across the board to all people? How do we get equity across the state?”

Partnership and Community Building

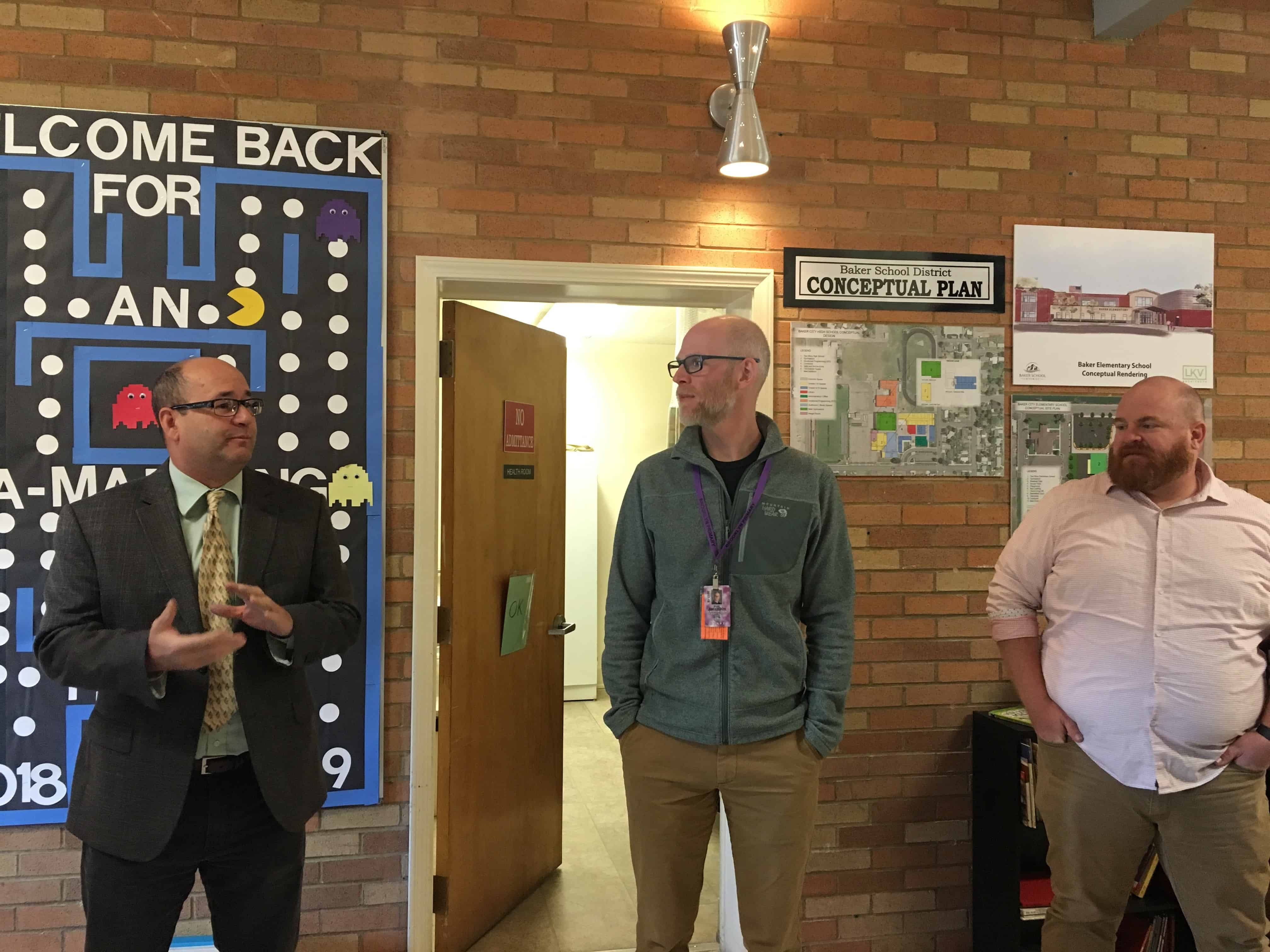

At a kick-off meeting at the school district’s headquarters, a coalition of the willing began formulating a plan. The folks around the table represented multiple sectors of early childhood care and services. The local librarian was present, as was a nutritionist, multiple preschool teachers, experts in behavioral health, school administrators, medical service providers, and other early childhood advocates.

Many wear multiple hats in the community, like Rob Dennis, Baker’s 5J community liaison who also serves as the town’s high school football coach, and who is about to welcome a 3-year-old girl into his family.

Dennis led the meeting by outlining a sobering picture of student demographics and academic achievement trends: 60 percent of Baker students qualify for free and reduced lunch; the student population is subject to high turnover; academic achievement is trending down.

Yet, the mood around the table was engaged and positive as representatives began discussing the need to share data, cross-collaborate, and engage parents and community partners. “This is work we need to do, but not work we can’t do,” said Dennis.

Members of the planning group were especially cognizant of the need to incorporate parent voice throughout the process. That means reaching out in virtual spaces like Facebook Moms groups as well as to places where parents already go—like the Moms, Pops, and Tots class offered through the YMCA.

That broad sense of community responsibility and connection was also reflected in the thoughts shared by Susan Townsend, a self-described concerned citizen and retired educator. “This is not a school district thing,” she said. “It is a community thing. It’s everyone at this table making a contribution for the good of our kids.”