Oregon’s Push for Increased Public Investment

This article was written by Nicole Hsu and originally shared through New America on May 15, 2023. The link can be found here.

Across the nation, people are connecting the dots on just how critical strong early childhood infrastructure is for the nation’s overall economic well-being. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the fragility of the early childhood system to the public, demonstrating and demanding the need for increased public investment.

As President Biden and members of Congress continue to take steps to make child care more accessible and affordable at the federal level, state legislators are also championing a strong early learning system that supports children, families, and providers.

Like many states, Oregon is facing a child care crisis. The state faces an estimated negative economic impact of $1.4 billion each year because families cannot access consistent child care. A 2020 analysis of Oregon’s pre-pandemic child care supply found that all counties are child care deserts for infants and toddlers, meaning there are more than three infants and toddlers for every available child care spot. The availability of child care isn’t much better for preschool-aged children, where 25 of the 36 counties are child care deserts.

Over the years, collective advocacy and organizing efforts led by groups such as the Early Childhood Equity Collaborative, Early Childhood Coalition, and Child Care for Oregon have resulted in more state investment in early childhood, including raising child care reimbursement rates. The Student Success Act, passed in 2019, doubled the state’s investment in early learning and care from $400 million to $800 million over two years.

But, as Dana Hepper, Director of Policy & Advocacy at the Children’s Institute, an Oregon-based policy, research, and advocacy organization, noted, the state still has a long way to go to serve all of Oregon’s children and families. Among this year’s child-centered legislative priorities are increasing funding for the Early Childhood Equity Fund, a dedicated funding source for culturally affirming early childhood programming, and increasing child care subsidy reimbursement rates.

In addition, advocates want to reduce barriers to entering and moving up in the profession. Before the pandemic, between 25 to 30 percent of Oregon’s child care workforce left every year. Even without the latest numbers, Hepper shares, “We anticipate that it’s only gotten worse. So we knew it was a crisis before, and that crisis has only been exacerbated, which just increases the need to do something about it now.”

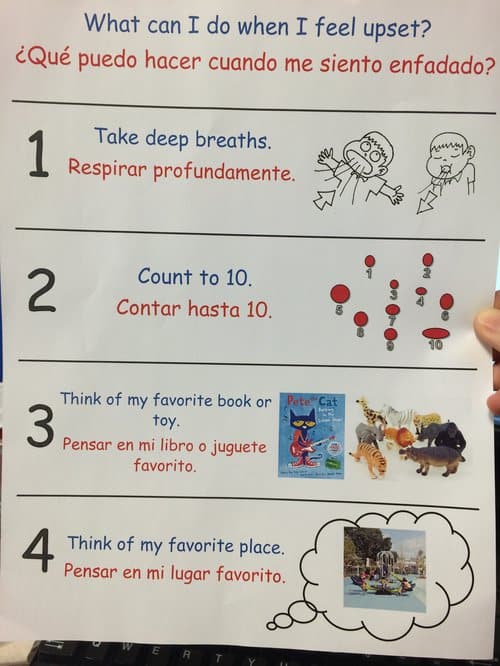

There are not enough people currently in or entering the profession to fill these jobs. To create accessible and equitable workforce pathways, HB 2991 would require the Department of Early Learning and Care to commission a study to identify barriers and inefficiencies in the early childhood profession. The study would result in recommendations to streamline credentialing and credit transfers, include clear standards for reviewing qualifications and experience, and provide access to materials in different languages that reflect the linguistic diversity of the workforce.

Yet, even if the state were to solve the workforce shortage crisis and have a sufficient and stable workforce, it would not have adequate physical space necessary to provide care for all children who need it. Investment in a robust, diverse workforce needs to be paired with investment in physical spaces where learning happens. And, the investment needs to extend to all learning settings within Oregon’s mixed-delivery system.

In interviews conducted last year as part of the state’s Preschool Development Grant, families with young children reported a clear need for child care options in rural and remote areas, that reflect non-traditional working hours, and for families who speak languages other than English. Home-based providers, making up almost a quarter (23 percent) of Oregon’s early childhood workforce, are more likely than center-based providers to meet these needs. Because where they live is also where they work, there is a need to clarify the rights of home-based providers who are renters and their landlords. SB 559 would ensure that landlords cannot prohibit renters from operating licensed home-based child care programs and provide protections for both parties.

Furthermore, early childhood providers are small business owners. They face costs associated with establishing, expanding, or maintaining a learning environment that is safe and developmentally appropriate for young children. However, differences in the types of loans and state funds available to providers across the mixed-delivery system, along with the complex and costly system of zoning and permitting, result in inequitable access to capital for child care infrastructure.

Local efforts to expand and improve child care facilities in all early childhood settings, like San Francisco’s Child Care Facilities Fund, have become models for California’s new statewide Child Care and Development Infrastructure Grant Program. Oregon is hoping to establish something similar with HB 3005, which would allot $100 million towards a Child Care Infrastructure Fund to finance new and existing early learning and child care facilities, with a 25 percent minimum allocation to culturally specific early childhood programs and a 25 percent maximum for school districts. In addition, HB 2727 would initiate a review of zoning, land use, and building codes and make recommendations to improve permitting processes to support the expansion of early childhood facilities.

In 2022, when the state legislature allocated $22 million towards the Child Care Capacity Building Fund, more than $170 million was requested in the first round of applications. In addition, research conducted by the Children’s Institute estimates that around $40 million worth of early childhood facilities across the state are ready to expand with a pipeline of more than $40 million worth of facilities that would apply for funding if such a fund is created.

Source: Children’s Institute

Early childhood champions in Oregon are advocating for increased public investment in child- and family-centered policies without compromising on the state’s longstanding commitment to a mixed-delivery early learning and care system. For the state, at this particular moment, this means public investment in the workforce and infrastructure. At the end of the day, Hepper hopes “people see Oregon as a place that is really pushing the envelope and being really innovative in terms of solving these challenges facing children and families. And, as a state who knows that this is work we need to come back to session after session.”