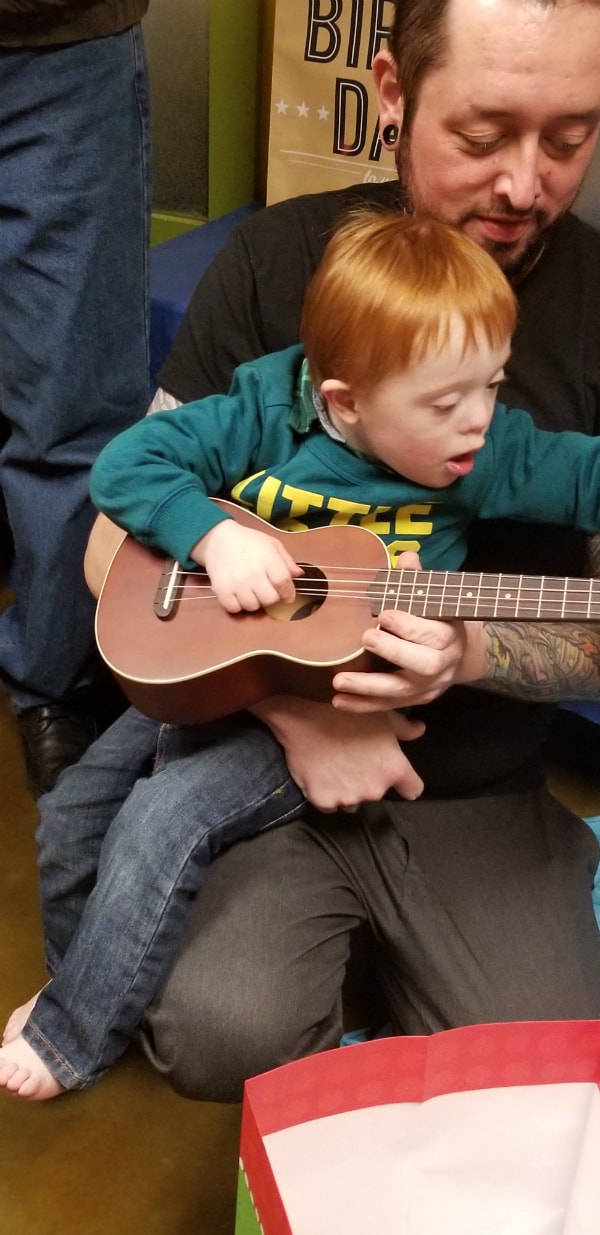

Miles Wolpoff, 5, with his family, photo courtesy of Darcy Jeffs. Photo by Dan Haberly.

One Oregon couple in a rural town south of Eugene sends their 3-year-old autistic son on a two-hour round trip bus ride so he can attend a special state-sponsored preschool.

A couple living on the coast rent an apartment in Eugene where the mom lives during the week so their 4-year-old autistic son can get services beyond what the state provides.

A single-mom on Oregon’s eastern border makes 90-minute round trips two or three times a week to the Boise area in Idaho so her son with Down syndrome can get therapy unavailable locally.

Oregon Lacks Resources for Young Kids With Special Needs

Administrators and parents say Oregon lacks resources and professional staff to adequately help young children with special needs, especially in rural areas where services are strained by distance, limited public transportation, a scarcity of therapists and language barriers.

As required by federal law, the Oregon Department of Education provides early intervention for children under 3 with developmental delays and disabilities and early childhood special education for children 3 to 5 until they enter kindergarten. The Early Intervention/ Early Childhood Special Education (EI/ECSE) program operates through Oregon’s education service districts (ESDs) and their contractors to help children with physical, cognitive and social-emotional development.

But providers and parents say Oregon’s resources have not kept pace with rising costs and a growing number of young children eligible for services. By investing more in these children early, Oregon could reduce the number needing special education later, says Judy Newman, director of Early Childhood CARES, which is based at the University of Oregon and contracts with Lane ESD to provide education and therapy services for 1,500 children countywide.

“We know from brain development research, the earlier we get on this, the better chance we have of minimizing or eliminating problems,” says Newman.

But sometimes in Oregon, especially in rural areas, it is not so easy to act early.

The Long Bus Ride

Jessilyn and Nathan Whiteman discovered the formidable challenge of getting services for their autistic son, Christopher, when he reached his third birthday. Until then, the Douglas ESD based in Roseburg sent specialists 40 miles north to the Whiteman’s home in the small town of Drain to help Christopher with speech and occupational therapy twice a month.

But once the boy turned 3, he had to go to the ESD’s special education preschool in Green, a small town just south of Roseburg, for services.

Jessilyn, 35, works at an insurance company in Drain and her husband, Nathan, 36, works for a railroad company on the Oregon coast. Neither could take Christopher to the preschool. So, on the advice of professionals, they reluctantly put him on a small bus alone and sometimes as sole passenger for two-hour roundtrips to the Green preschool twice a week. Strapped in his seat on the long bus rides, Christopher sometimes screamed, threw his shoe at the bus driver, and vomited.

Christopher Whiteman, photo courtesy of Jessilyn Whiteman.

“There were things he liked about it,” says Jessilyn. “But to go to a two-hour preschool, he would be gone four hours…Too much.”

Administrators elsewhere in Oregon, however, say it is not uncommon for parents to put their 3- and 4-year-old children on long bus rides for special education services. Children, for example, sometimes ride an hour from rural outskirts of the 688-square-mile Columbia County to preschools supported by the Northwest Regional ESD in five cities, says Cindy Jaeger the county’s EI/ECSE service center administrator.

The Whiteman’s have since moved into the big, boxy home Jessilyn grew up in among trees and fields on the edge of Yoncalla, a small town six miles from Drain. Now four mornings a week, Christopher attends school at Yoncalla Elementary, both in the preschool established with help from the Children’s Institute’s Early Works program years ago and in a second special education preschool the Douglas ESD recently opened there. The ESD also gives Christopher a weekly half-hour of speech therapy. Having him close has produced enormous benefits, says Jessilyn, who also home schools her older son.

“If he is having a meltdown at school,” she says, “I can just drive over there and get him.”

Once a week, Jessilyn drives her son 44 miles north to Eugene for an additional hour of speech therapy. Despite his dramatic improvements in speech and behavior, she says she wants to somehow do even more for Christopher.

“I’m nervous about kindergarten,” she says, “because I’m not sure he’s ready.”

Some, But not Enough

Like the Whitemans, rural parents across Oregon get state help for their young children with special needs, but many feel it is just not enough.

In Tillamook County, for example, the Northwest Regional ESD provides early intervention visits to children under 3 only one hour a month, though occasionally two hours a month for children with severe needs, says Kim Lyon, the county service center administrator. The ESD operates preschool for 3- and 4-year-olds only two hours a day twice a week.

Services are “very limited,” Lyon says.

Neighboring Columbia County has seen the number of children qualifying for services jump by 49 percent, from 150 to 223, over the last two years with a minimal budget increase, says county administrator Jaeger. The county employs “excellent professionals,” she says; “There are just not enough of them.”

Early Childhood CARES, the program directed by Judy Newman, operates a preschool in the coastal town of Florence that was a godsend for Miles Wolpoff, the 5-year-old son of Darcy Jeffs, 39, and her fiancé, Kevin Wolpoff, 42.

Miles Wolpoff, photo courtesy of Darcy Jeffs. Photo by Dan Haberly.

Miles, who would soon be diagnosed with mixed receptive expressive language disorder with autism, enrolled in the preschool in September of 2017 for three morning hours four days a week. Darcy, a freelance graphic artist, attended school with him for two months and saw that he struggled to “fall into line” with the class of eight, all with special needs. Sensitive to loud noises, for example, Miles would stray when children were grouped in a circle to sing or dance.

But when Darcy revisited the class the following April, she was astounded by changes in her son. He could follow directions, both verbal and those represented by photos and pictures.

“He’s sitting for circle time,” she says. “He was singing. He was doing all the motions. I started crying.”

The state-sponsored preschool in Florence helped Miles take big leaps in his speech, social, and daily living skills. Even so, says Darcy, “I felt like he needed more.”

To get more, she had to leave Florence. She’d already been driving him each Friday 75 miles away on the winding State Highway 126 to Eugene for an hour of speech and occupational therapy. The parents then enrolled him in another Eugene program offered by a non-profit agency called The Child Center, which combines applied behavior analysis (ABA) therapy with preschool for six hours a day, five days a week. Enrolling Miles meant Darcy drove three hours round trip daily. Fortunately, she soon found an affordable Eugene apartment for her and Miles during the week.

The Right Therapy Makes a Big Difference

The ABA therapy is data driven, designed specifically for autistic children and has powerfully improved Miles’s communication, adaptive, emotional regulation, and social skills, says Darcy.

“Communication has been the biggest hurdle,” she says. Now, after his Child Center experience, she says, “not only can he tell us what he wants to eat or activities he wants to do, but he also can tell us what he doesn’t want to do.”

Miles’s gains come at the cost of missing time with his father, a contractor in Florence, who reads bedtime stories to him via Facetime. Darcy says she knows other Florence parents who cannot afford to take their children with special needs to Eugene.

“Seeing how much positive effect we’ve had from this more rigorous therapy, it just makes me feel bad for other families that can’t or don’t,” she says.

Melissa Tyler, 43, a single mom studying in college to become a social worker, also had to leave her town—and state—to get additional help for her 4-year-old son, Mason, who has the Down syndrome genetic disorder.

With state support, Mason attends a preschool in his home town of Ontario with a population of 11,000 on the state’s eastern border, and he gets 100 minutes a month of speech and occupational therapy. But it is “not enough,” says Tyler. She makes the 90-minute round trip two or three times a week across the border to the Boise area to give her son the additional therapy she thinks he needs.

“He has made huge improvements in his verbalization and in his fine motor skills since we started doing the additional speech and occupational therapy,” she says.

Mason Tyler, photo courtesy Melissa Tyler

Oregon’s Investment

Oregon’s Early Intervention/Early Childhood Special Education program, which includes some federal funding, operates on a two-year budget for 2017–19 of $228 million, about 15 percent of it federal. Between 2012 and 2018, the number of students in the program rose 21 percent to 13,832, and state funding per child climbed 33 percent to $8,726.

Despite funding increases, challenges remain statewide in getting adequate services, and those are compounded in rural areas by distance and limits on access to specialized staff, quality child care and early learning programs, says Kara Williams, director of EI/ECSE and Regional Programs for the Oregon Department of Education

The department reports one third of eligible kids under 3 get the recommended level of early intervention service they need. “Recommended level” means about average as opposed to low- or high-quality, says Newman, the Early Childhood CARES director. About two thirds of 3- and 4-year-olds in special education with low needs get the recommended level, and among those with moderate needs, the portion is 14 percent. Only two percent of those with high needs get the recommended level of service.

The state education department projects that if Oregon increased annual spending on early intervention and special education by $76 million per biennium, it could provide all children with recommended levels of services. That would save money downstream in kindergarten and public school by reducing the number of children in special education and the scope of services they would need.

Heavier investments early also could ease the stress, travel time, and costs that afflict so many rural parents striving to help their children succeed in school and life.