Spanish-language Professional Development – Adelante Mujeres

At Adelante Mujeres, many of our teaching staff wanted to continue their education. Most of our teachers’ primary language is Spanish, but college courses were only offered in English. In addition, our teachers needed environments in which they felt welcomed and comfortable learning about Early Childhood Education (ECE).

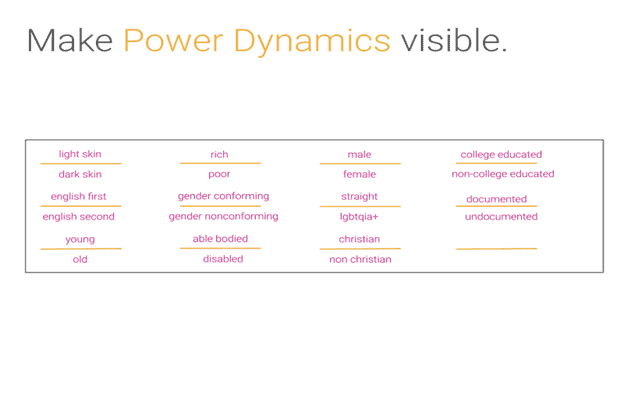

Often, people who are not fluent in the English language are held back from obtaining a higher education due to the language barrier. They have the knowledge and experience but are first required to learn English. This can deter professionals. In addition to navigating the language barrier, our teachers needed to feel welcomed and supported as they were applying to college as first-generation students. We knew that we needed to find new ways to encourage our teachers and empower them.

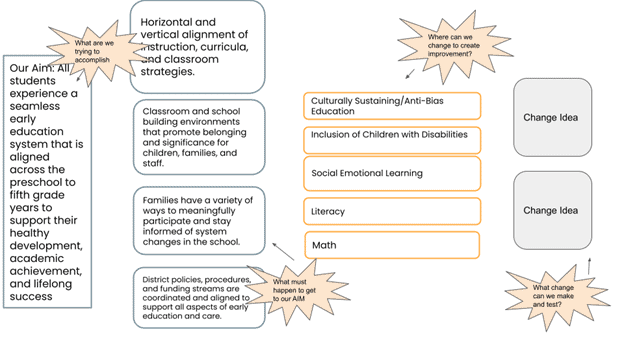

Change Idea:

We partnered with Clackamas Community College to ensure that our teachers could have access to ECE courses in Spanish. We also had a specialist help them create their professional learning plan to navigate Oregon’s Early Childhood system.

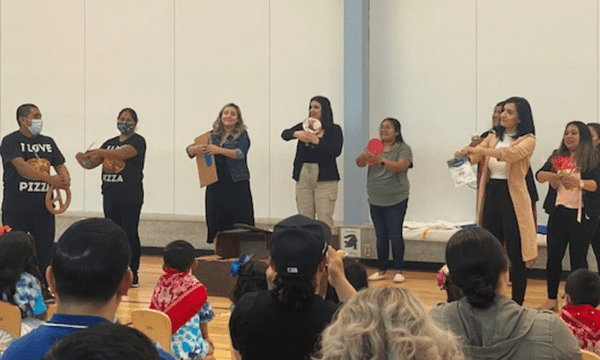

Our Director of Education Programs advocated for teachers and worked closely with Clackamas Community College to help develop a Spanish language Early Childhood Education associate degree pathway. We also created new workshops that are culturally relevant and true to ancestral knowledge. By honoring our culture and values we reclaim and redefine education.

Teachers have been taking college courses and are on their way to completing an associate’s degree, bachelor’s degree, and/or Child Development Associate credential. In addition, our nonprofit and our partners provide financial aid for courses and professional development in Spanish. Our in-house workshops are tailored to the cultural and holistic needs of our teachers.

We hope this change will mean that language will no longer be a barrier for teachers wanting to further their education. We want them to feel empowered to lead and support children and families. But we understand that navigating the college system was only one part of the challenge.

Currently, Clackamas Community College continues to offer ECE courses in Spanish which is a great opportunity for ECE teachers. We continue to evolve and learn new ways to support our teachers in holistic ways. We understand that systems have been created to dismantle or discourage personal growth for non-white people. It is not enough to provide education in Spanish but to ask ourselves if our teachers feel that they belong and are valued at our center. This change is perpetual and requires constant reflection and refining.

Status of the Change Idea: Adapted, Adopted, or Abandoned?

Adopted

Additional Resources

Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paolo Freire

“One cannot expect positive results from an educational or political action program which fails to respect the particular view of the world held by the people. Such a program constitutes cultural invasion, good intentions notwithstanding.”

― Paulo Freire