Yet, general understanding of infant and early childhood health is still at an emergent stage. That’s partly because diagnostic classification of mental health and developmental disorders in children under 5 did not exist until 1996. While treatment and payment protocols have been established in Oregon since then, more work is needed to integrate infant and early childhood mental health into the larger array of available services and supports for families and children.

Here are five answers to questions about infant and early childhood mental health in Oregon:

What does mental health in an infant or toddler look like?

Social and emotional health in the youngest children develops within safe, stable, and attached relationships with caregivers. Children who have positive and engaging interactions in their earliest years are more likely to enjoy good physical and mental health over their lifetimes. They are also better able to experience, regulate, and manage their emotions—key skills for later school readiness.

What types of mental health issues and disorders do young children suffer from?

Children who suffer from abuse, neglect or trauma—especially those facing additional barriers such as living in poverty—are more susceptible to mental health issues, including attachment and emotional regulation disorders and other developmental or psychological disorders.

Laurie Theodorou, Early Childhood Mental Health Specialist at the Oregon Health Authority (OHA), says very young children can also suffer from the same disorders that affect older children.

“Depression and anxiety can be seen even at the pre-verbal level. Though they can be harder to diagnose, young children respond well to therapy that includes their parent,” she said.

She’s also careful to note that mental health issues and disorders are not limited to situations related to maltreatment. “It’s important to de-stigmatize mental health and mental health treatment… Parents can be doing everything right and still need additional help for their child’s social emotional or behavioral problems.”

How are infant and early childhood mental health issues treated?

Proper screening and assessment are key to identifying and treating young children who are at risk for or suffering from mental health issues or disorders.

Treatment for mental health issues and disorders can be provided in a variety of home and clinical settings. Evidence-based treatments are family-centered and use attachment-focused approaches, including infant-parent psychotherapy, Parent Child Interaction Therapy, and psychoeducation.

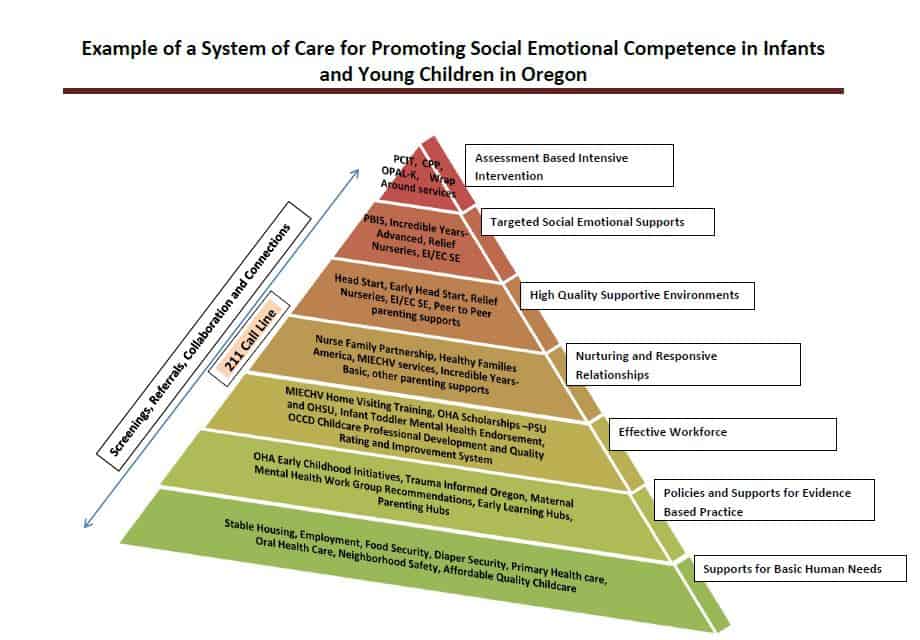

Source: The Oregon Children’s System Advisory Council (CSAC) 2015; Early Childhood Workgroup. Adapted from TACSEI, www.challengingbehavior.org and http://csefel.vanderbilt.edu/ April 2015

What policy strategies can help improve outcomes for young children?

Researchers Joy D. Osofsky of Louisiana State University, and Alicia F. Lieberman of the University of California, San Francisco, recommend four actions to improve awareness and action on early childhood mental health issues:

- Expand early screening for infants and toddlers to detect mental health issues.

- Train professionals in mental health, pediatrics, early childhood education, child welfare, and other related professions to recognize risk factors; and ensure that undergraduate, graduate, and continuing professional education include content on infant mental health.

- Integrate infant mental health consultations into programs for parents, child care, early education, well-child health services, and home-based services.

- Address insurance and Medicaid payment policies to provide coverage for prevention and treatment of mental health issues for infants and toddlers.

How is Oregon working to improve public policy and practice for infant and early childhood mental health?

Oregon’s efforts to build a system of care for infant and early childhood mental health have been steadily building. For example, Oregon’s adoption of developmental screening as an incentive metric for Coordinated Care Organizations has increased the numbers of children identified for further assessment. The creation of a diagnostic crosswalk—a guide that aligns multiple diagnostic classification manuals—has also made it easier for providers to be reimbursed for mental health treatment.

More recent and upcoming developments include the planned roll-out of universally offered, voluntary home visiting in Oregon, and Project Nurture, an integrated model of maternity care and addiction treatment for pregnant women with substance use disorders.

A number of workforce-related efforts have strengthened the existing network of support for Oregon’s youngest children. OHA and the Oregon Infant Mental Health Association have partnered to offer an infant and early childhood mental health endorsement for early care and education and mental health professionals. An infant/toddler mental health graduate certification is available at Portland State University and the school has also introduced a new, two-year scholarship program to study rural infant mental health with funding from The Ford Family Foundation.

Raise Up Oregon, the state’s early learning systems plan, and the passage of the Student Success Act also promise to bring more attention and resources to the ultimate goal: a network of support for all children beginning at the prenatal stage which sets children up for future academic and lifetime success.