Imagine you’re an Oregonian earning a median-level household income of $78,683 a year. Let’s also imagine you’ve just become a new parent and are researching infant-toddler care options in advance of your planned return to work.

Do you choose a child care option that costs 11 percent of your total household income? Twenty percent? Thirty-nine percent?

What if those cost differences also reflected the relative quality of those care options? How much are you willing to pay for high-quality care?

Cost vs. Quality Amid a Scarcity of Choice

For many Oregonians, this hypothetical calculus is all too real. A new analysis by the Center for American Progress (CAP) highlights the uncomfortable reality parents face when seeking infant-toddler child care. CAP analyzed data from all 50 states to come up with average costs for care, distinguishing between child care options that meet minimal standards for care and those that offer “high-quality” care.

High-quality care includes settings where caregivers have received more advanced training in child development and where staff ratios surpass minimum legal requirements.

For your hypothetical family, home-based child care meeting the most minimal of licensing standards will cost approximately $8,655 per year, or 11 percent of an Oregonian’s median household income. Center-based child care serving infants will cost you $15,736 per year, or 20 percent of the median household income. And high-quality, center-based child care will cost you a jaw-dropping, $30,686 per year, or about 39 percent of the median household income.

Even for those earning more than Oregon’s median income, an $8,655 per year child care bill is no bargain. But for those who can afford to pay it, securing a child care spot for an infant or toddler, comes with another layer of challenge: lack of availability.

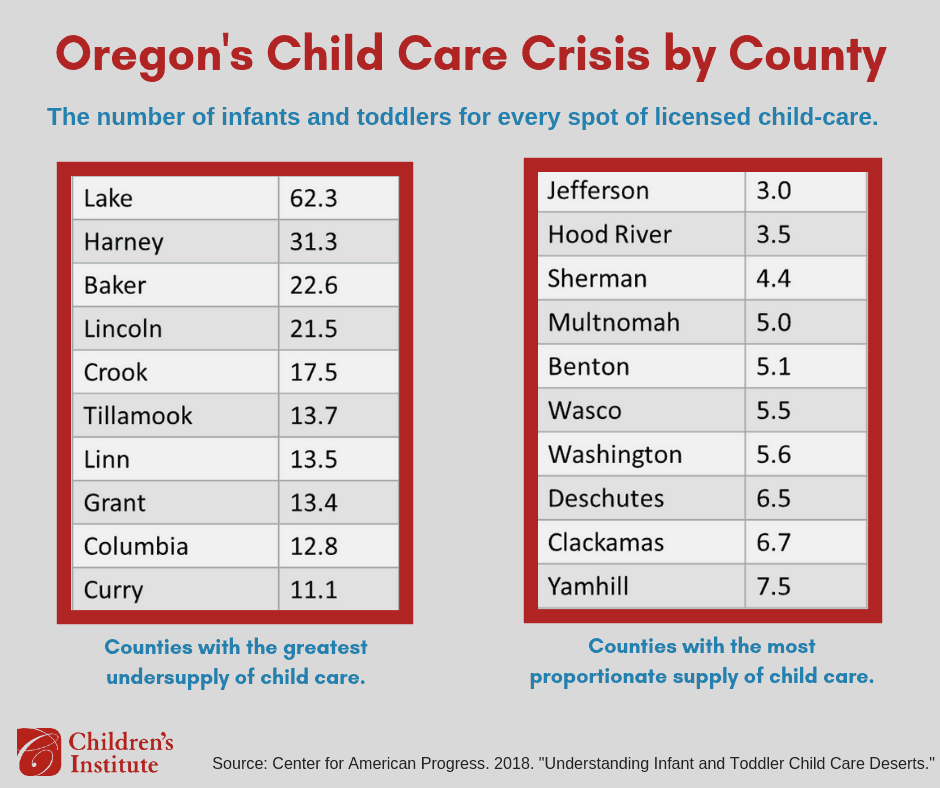

CAP analysis shows that In Multnomah County, there are five children for every available infant-toddler child care slot. In Harney county, there are 31 children for every available slot. In Lake County, there are 62 children for every available slot.

Infant-Toddler Care Offers Little Financial Incentive to Providers

Much of the scarcity is due to the fact that there just aren’t a lot of financial incentives to care for infants and toddlers. A certified, center-based child care provider must staff infant rooms at a 1:4 staff to child ratio; 24–35-month-olds at a 1:5 ratio; and 36-month to kindergarten-age children at a 1:10 ratio. But centers know that charging the parents of infants more than twice as much as the parents of a 3-year-old is not practical, so they effectively subsidize the cost of younger children with the rates charged to older kids.

Registered home-based providers in Oregon generally care for fewer children across a broader age range. Their licensing requirements call for a 1:10 staff to child ratio. However, only two out of 10 children can be under 24 months old, which also limits availability to parents seeking care for children under 2.

Another quirk in the child care picture is that efforts to offer public preschool opportunities to more children in Oregon could exacerbate the problem of cost and scarcity in infant-toddler child care. As child care providers often subsidize the higher cost of infant-toddler care with the relative lower cost of care for 3- and 4-year-olds, broader access to public preschool in Oregon could actually put more pressure on the operational cost of providing child care as preschool-aged kids would likely leave for (free) public options.

DIY Child Care

CAP has created an interactive tool which allows users to modify various elements of child care to better understand the cost of providing quality care in Oregon and other states. Click the image to try it yourself.

Source: Center for American Progress.

Low-Income Families Struggle to Cover Affordability Gap

Given that 19 percent of Oregon’s children ages 0–5 live at or below the poverty line, how do parents earning low-income wages work if they need child care?

Oregon offers child care subsidies funded primarily by a federal block grant to low-income working families. However, the CAP analysis also demonstrates that in Oregon, there is an $83 per month difference between the cost of center-based care for an infant and what the state offers in child care subsidy assistance.

Governor Kate Brown’s latest budget proposal calls for a $10 million investment in Baby Promise, a program that seeks to increase access to child care in a variety of settings. Recognizing the need for a significant public investment in child care is a step toward creating an early care and support system for children and families that works.