Oregon is in a child care crisis. As many working parents know, finding reliable and affordable child care from a trusted provider is not easy. According to a study by the Center for American Progress, Oregon is a child care desert, defined as a place where there are more than three children per licensed, available child care slot. Infant-toddler care in Oregon is even scarcer, with 6.8 children per slot. These findings, in addition to Oregon’s ranking as the third-least affordable state for licensed, center-based care adds to mounting evidence that Oregon’s child care system is in dire straits. Our state’s inability to build a supply of quality child care options for working families threatens the safe and healthy development of our most vulnerable young children.

Every day across Oregon, thousands of young children are cared for by people other than their parents. Parents need this child care to be safe and reliable. At the same time, young children need responsive and nurturing relationships with caregivers to stimulate their growing brains. Babies are born learners and what happens in early childhood largely shapes their later life experiences.

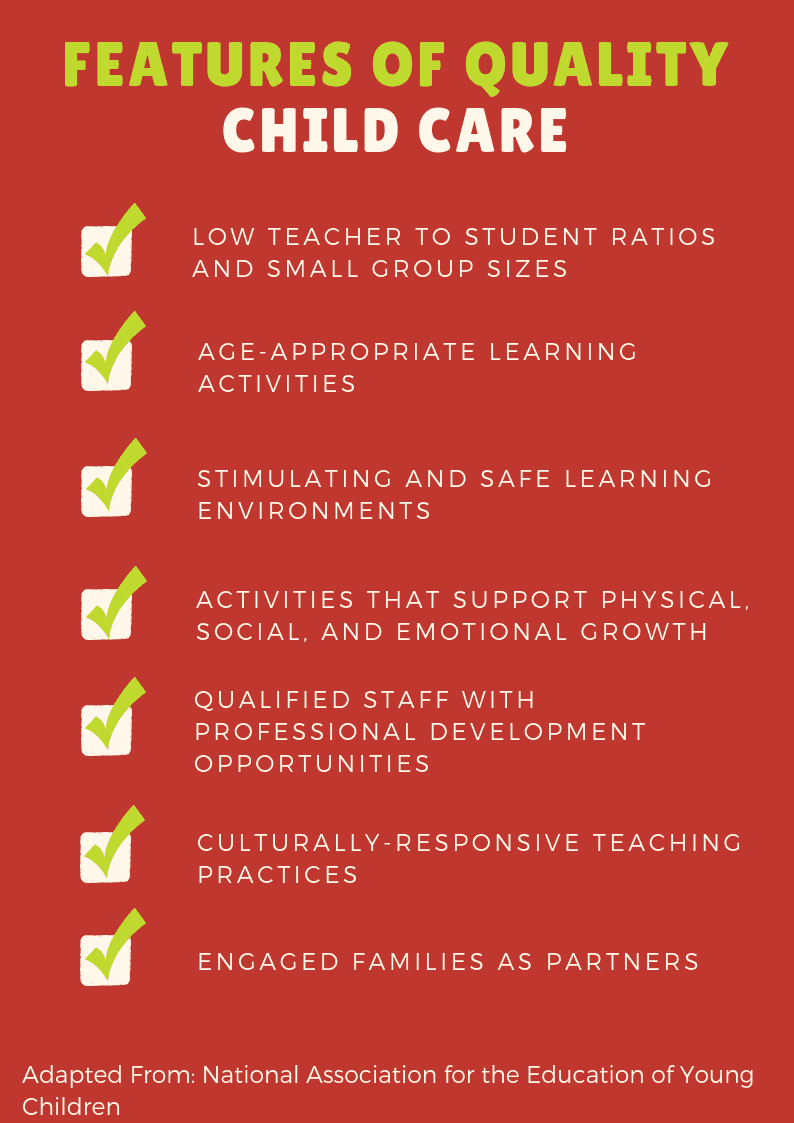

When it Comes to Child Care, Quality Matters

Quality child care is provided by well-trained caregivers who understand and can support a young child’s brain development. This level of care supports early education, teaching young children foundational reading, writing, and math skills that stimulate their rapidly growing brains and strengthens their natural love of learning. Well-trained and skilled child care providers may also be the first adult in a young child’s life to recognize an emerging developmental delay or disability.

Providers know, and brain research conducted over decades tells us, that the early years from birth to 5 are a time of profound brain development, when the opportunity to positively influence children’s social-emotional and decision-making skills is greatest. Children who receive quality care in their early years are more likely to be ready for kindergarten, read proficiently at third grade, graduate from high school, and attend college. As adults, they are healthier, earn higher incomes, and are less likely to have interactions with the criminal justice system.

Quality Care Comes at a Price

Licensed and regulated care for babies and toddlers is extremely expensive to provide. Child care is labor-intensive work and licensed settings are required to follow safety and staffing ratios. This makes it difficult to economize on the largest share of their overhead costs, which are devoted to payroll. Oregon recently earned the undesirable distinction of being the third-least affordable state in the country for center-based care. According to the Economic Policy Institute, one year of infant and toddler day care in Oregon is more expensive than public college tuition.

Child care subsidy programs like Employment Related Day Care (ERDC) have not been able to sufficiently address child care costs for low-income Oregonians, who also pay some of the highest co-pays in the nation for care.

This means that many parents, whether they are paying the full cost of child care or are eligible for subsidies, find quality child care extremely difficult—if not impossible—to afford.

Despite High Costs, Providers are Still Paid Far Too Little

Adding to the economic complexity of child care is the fact that we just don’t pay early childhood workers enough for the important work we expect them to do. In Oregon, wages in 2017 for child care workers averaged $11.47 per hour—on par with the earnings of office receptionists, janitors, and general laborers. Not surprisingly, the early childhood profession suffers from high turnover.

Given the high costs of child care that parents already pay, it is not feasible to expect them to pay even more to increase wages for child care providers. In countries with economies similar to the United States, child care costs are heavily subsidized by governments or employers. Solving the problem in a comprehensive or sustainable way will be difficult without a major commitment from Congress, along with increased state and private investment. If we continue to leave families to solve the issue of child care on their own, our entire state will suffer.

What Happens When There is No Care?

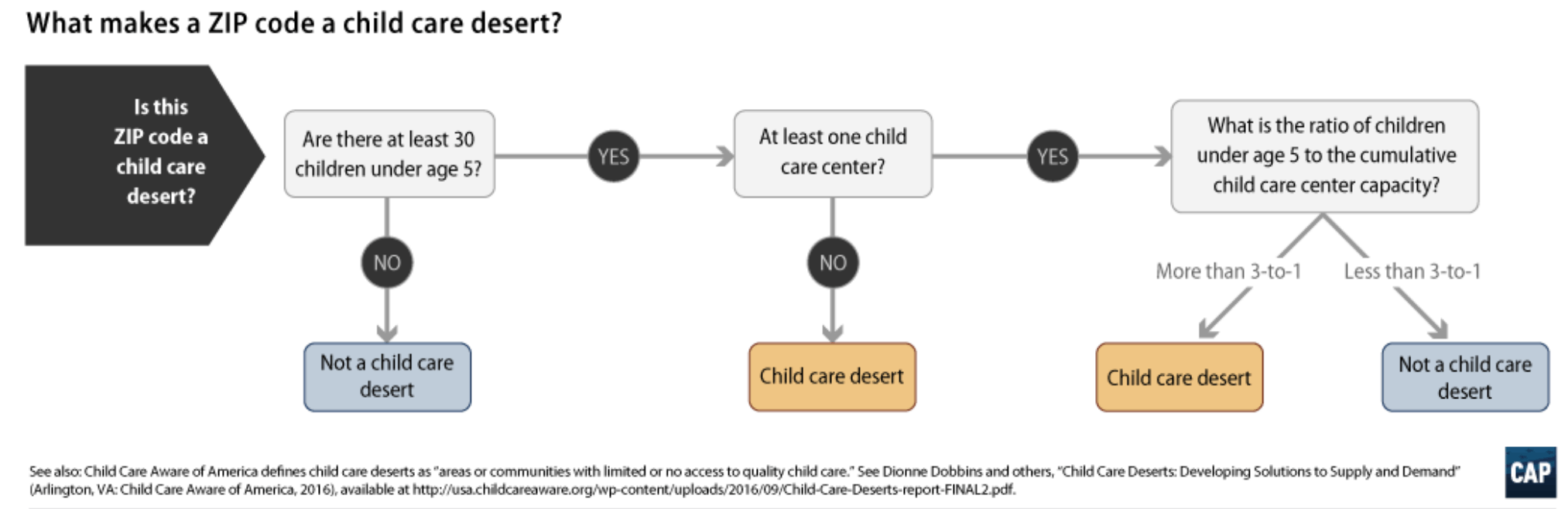

After analyzing data from 22 states, the Center for American Progress found that more than half of Americans are now living in “child care deserts”—neighborhoods or communities where there are more than three children for every licensed child care slot.

In 2016, the Center for American Progress borrowed terminology from the frequently studied issue of food deserts to create a working definition of child care deserts.

Not surprisingly, finding high-quality child care is especially difficult for families who:

- earn low-income wages

- need infant or toddler care

- live in rural areas

- have children with developmental delays or disabilities

- need “off-hours” or weekend care due to non-traditional work schedules

Immigrant and refugee communities, and communities of color are also disproportionately impacted by the lack of access to affordable quality care.

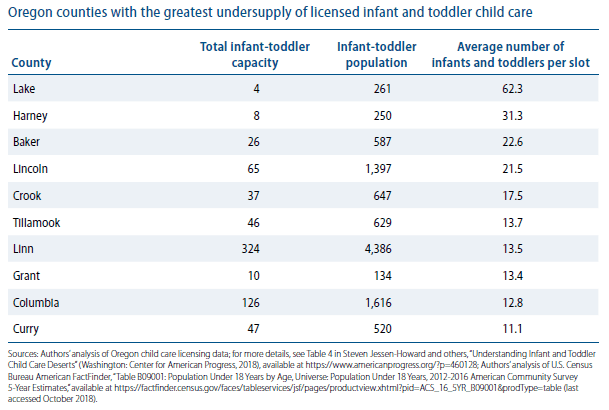

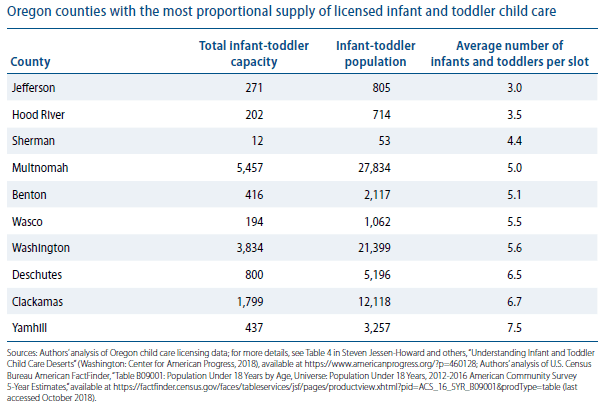

In a follow-up analysis of infant-toddler care across nine states and the District of Columbia, CAP compiled child care supply data from every county in Oregon. Notably, a greater percentage of families living in more remote areas suffered from an under supply of infant-toddler compared to those in urban centers.

A Closer Look at the Child Care Crisis in Oregon

Click tables to enlarge.

An Opportunity for Oregon

Very simply, the child care crisis affects all of us, not just those with young children. As a nation, we lose an estimated $8.3 billion a year in wages from parents who miss work due to a lack of child care. If Oregon continues to be a child care desert, businesses across the state will continue to lose workers.

Our failure to invest in child care systems has longer-term effects, too. Nobel Prize-winning economist James Heckman found that early childhood programs don’t just positively impact educational, health, and economic outcomes for children, but increase the work productivity of their parents, reduce crime, and improve property values, among other community benefits. Overall, Heckman estimates that investments in early childhood programs generate a 7–13 percent economic return rate.

“High-quality, reliable child care pays for the entire program before the child enters kindergarten. The economic gains of freeing mothers to enter the workforce, build skills and earn income pays for the cost of the program in the short-term while long-term benefits for children accrue into adulthood.”

— James Heckman, Nobel Laureate Economist

Strengthening the Child Care System

Children’s Institute believes Oregon can make progress on the child care crisis by strengthening and stabilizing existing programs that work, focusing on the areas of highest need, and increasing the numbers of qualified workers. Oregon’s child care landscape is incredibly complex, but one thing is clear—access to high-quality child care is a critical part of the support young children need to stay safe, be healthy, and grow into successful adults. Learn more about our specific recommendations to help Oregon fund a child care system that works for all of us.