What We’re Reading

Improving Behavioral Health Care for Children in California, a report from California Children’s Hospital Association (CCHA) published in December 2019 outlines the major challenges to ensuring quality mental health care for children. In a 2020 interview with CCHA President & CEO Ann-Louise Kuhns. Kuhns delves into the background for the report, reminding readers that children across the country are in crisis. The report and interview are worthwhile reads for those in Oregon and other states who are seeking to improve mental and behavioral health care for children.

Summary

The number of children with mental and behavioral health needs in California and nationally continues to grow. Self-reported rates of mental health issues have increased among the state’s adolescents by 23 percent since 2005, and suicide is now the state’s second leading cause of death for youth between the ages of 10-24.

Left untreated, mental health issues can have significant negative impacts on a child’s future, including on their physical health, educational attainment, life expectancy, and future earnings. Conversely, investing sufficiently in children’s mental health can offer a protective effect against future adversity, nurture resiliency, and reduce the burden on educational, social service, and health systems down the line.

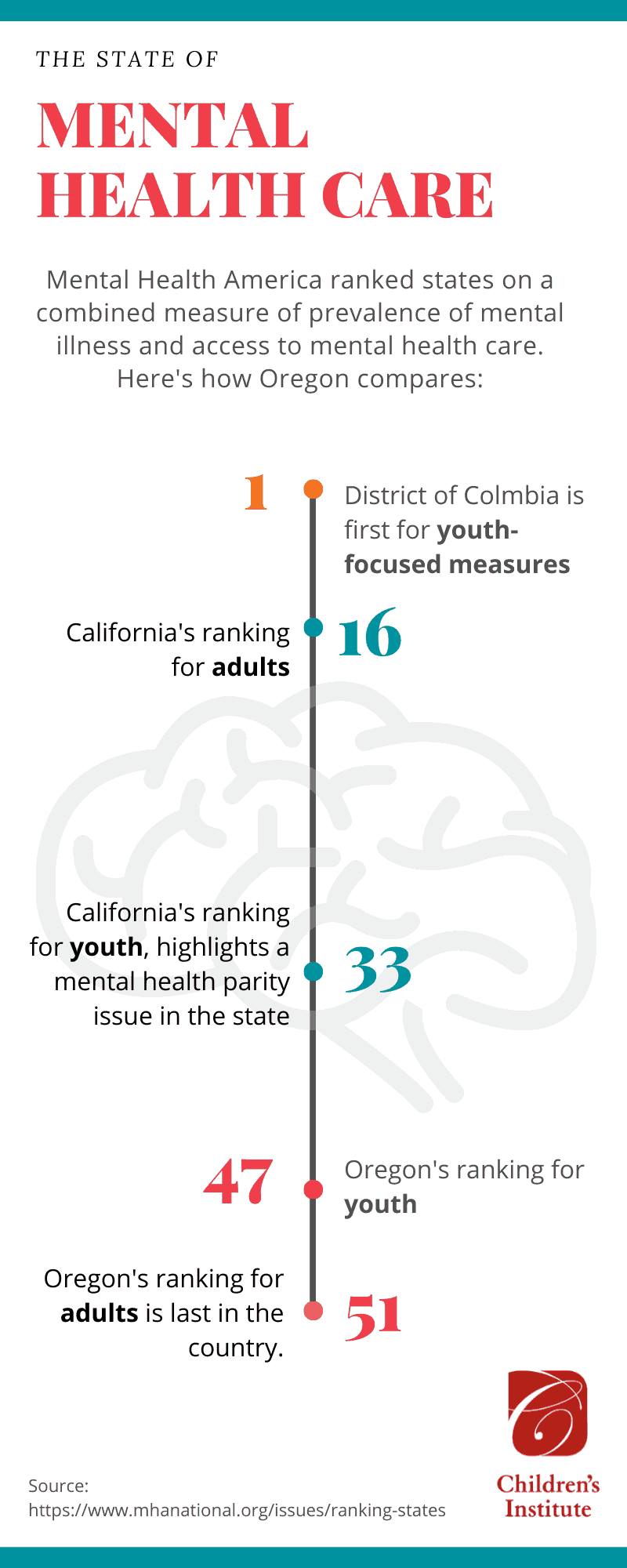

Those familiar with Oregon’s current childhood mental health care landscape will recognize similar themes and challenges.

A Graying Workforce, Not Enough Culturally-Specific, Bilingual Providers

California’s childhood mental health workforce is not robust enough to meet demand and the trendline is alarming. Nationally, there are only 8,600 child psychiatrists and 10,000 child psychologists. In California, the ratio of board-certified child psychiatrists to children in the state is 13:100,000. An estimated 45 percent of those doctors are over the age of 60, with retirement looming.

A shortage of providers is likely due to two reasons: working with children requires additional credentials, and those credentials don’t yield higher compensation compared to practitioners who only work with adults. In addition, the rapidly diversifying demographics of children in the state means that there are also severe shortages of bilingual providers and providers of color.

Systems of Care Are Not Aligned

Systems of care are often complex, bureaucratic, and are not in alignment with one another, resulting in confusion and frustration for families attempting to access care. Federal and state mandates meant to ensure access and parity of services for children often lack sufficient oversight or accountability. Providers shared that they spend an inordinate of time on paperwork, and that filling out paperwork for a new patient can take as much as two hours to complete.

As the report describes, “California’s pediatric behavioral health system is akin to the Winchester Mystery House, constructed asynchronously and illogically with haphazardly added rooms and doors that lead nowhere.”

Recommendations

The report includes recommendations that address access, quality, and accountability issues that are major barriers to meeting the mental and behavioral health needs of children including:

- Better enforcement of existing laws that ensure mental health parity for young people.

- Support for early intervention programs and integrated care models.

- Closing gaps in services, including increasing reimbursement rates, boosting investment in facilities and streamlining licensing and accreditation processes.

- Better coordination among providers and expanding e-health innovations and approaches like tele-medicine and tele-consultation.

- Greater investment in workforce training programs, including for providers who can deliver culturally and linguistically specific services.

Lessons for Oregon and Other States

According to Kuhns, the issues highlighted in the report are applicable to other states and nationally and she’s clear that states must lead the charge on system-level improvements.

From the Q&A:

“I think some of our recommendations, such as those having to do with enforcing mental health parity are national issues. The need for earlier intervention for children and adolescents also is universal. There’s a crisis for children across the board, across the country. Trying to help build resilience in children and help support families would be a good investment in our future, both in California and nationally. The same is true of our recommendations about supporting primary care providers to manage patients in their community practice so that children don’t have to wait so long for psychiatric treatment. We know that’s a model that works.”