Most of us are familiar with land acknowledgments, have heard them and have given them. As an Indigenous person, my feelings toward them, at this point, are mixed. I think, like all things racial justice, it’s an always-evolving conversation.

I get the growing feeling that Native people are starting to feel ambivalent about them. A few weeks ago, several of my colleagues and I watched a Land Acknowledgment Conversation hosted by Portland State University. During the panel, Shirod Younker, a Coquille and Coos artist, said, “It’s this stolen car that they keep driving past us, and they keep waving at us, saying ‘Hey, we stole your car!’ That’s what a land acknowledgment is, right?” When I sit in a room and hear an acknowledgment like this, I respond the same way Younker does. As he said, I “ball up.” It gets tiring to hear, “We stole this, and we broke it, and we’re not giving it back.”

I think it’s really important to be specific in an acknowledgment about how the work you’re in a space to do has included, or has not included, Indigenous people and perspectives, and how the work will affect Indigenous people.

I’m a member of the Okanagan Band of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, whose land is northern Washington state and up over the Canadian border, so even being an Indigenous person born and raised in Portland, I’m a guest here, too.

Many of us are guests in our respective homes today. In Portland, where Children’s Institute has its offices, we’re on land that has, since time immemorial, been home to many nomadic groups, including Chinook, Clackamas, Multnomah, Tualatin, Kalapuya, Kathlamet, Mollala, and Salish tribes. Indigenous people lived here for thousands of years, connected to the land and its place-specific teachings regarding how to live on it, unbothered and thriving. White settlement became the norm for this area only 163 years ago, which is six generations removed from us today.

When white settlement began, Indigenous populations were reduced by 90 percent over the course of one generation. Nine of every ten Indian people died from European diseases, or by violence, over the course of about twenty years. But the survivors were still fighting for sovereignty and the right to live on their land in the ways they always had.

These fights were violent. They were wars. And because of this, by the end of the 1850s, the remaining Indigenous survivors, of the illnesses and the fighting, were displaced from this land, their home, and confined to reservations. In Portland, that primarily meant the Grand Ronde reservation, about 70 miles southwest of my current home.

At the same time, Indian children were separated from their families and communities and sent to residential schools. Children from the area that is now Portland likely went to the Chemawa Indian Boarding School in Salem, where they were, at that time, prohibited from speaking their languages or participating in the cultural and spiritual practices that they had known all their lives. Assimilation to Western cultural norms was the goal of their education.

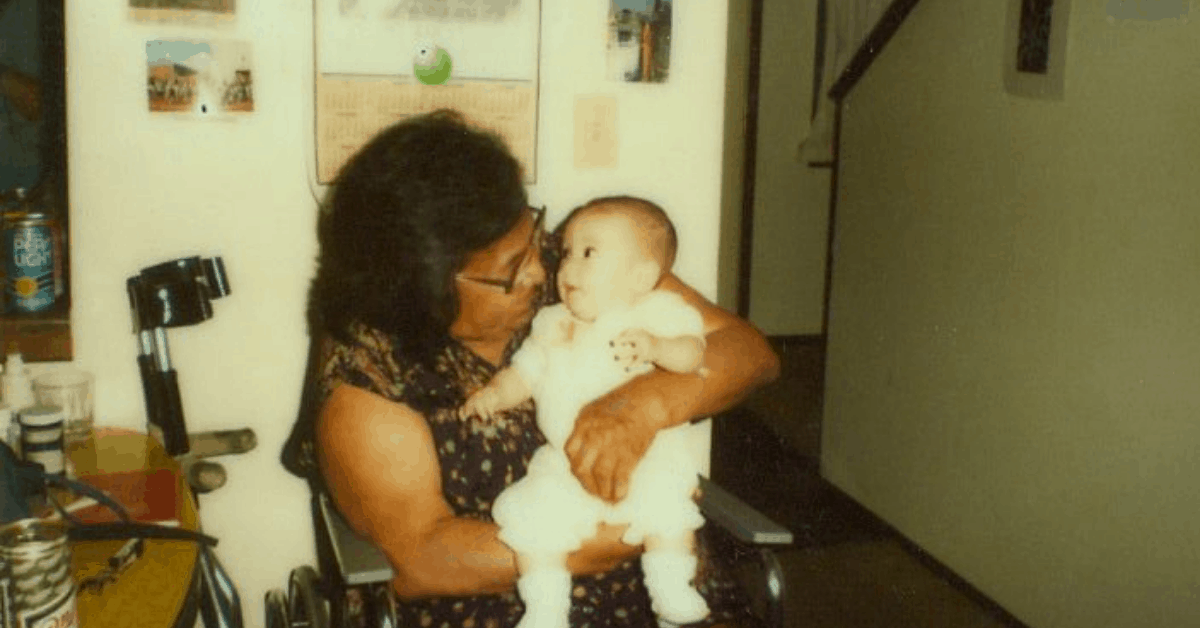

From that point, Indigenous people were, by law, not allowed to live within Portland’s city limits until the 1920s. For context or a frame of reference, that is when my tama, my Indian grandma, was a baby. Since then, of course, Native people have moved back into Portland, and descendants of this region’s Indigenous people are here today. And their culture is resilient. They still hold place-specific teaching about how to live on this land.

Ashley and her Grandma Lucy in Portland, 1982

Acknowledgment of these facts is worth nothing if it doesn’t inspire actions of reconciliation. And that is, I hope, a large part of the work we do every day every day at Children’s Institute. The effects of the colonization of this land have been, and are, experienced most harshly by Native children, Black children, children of color, and children whose parents are immigrants. This organization has a role to play in creating a system of caring for and educating children that contributes to a more just future.

I hope that when we gather, we can not only acknowledge the history of the land that we live and work on, but we can also critically examine the ways that we, and members of the communities that we work with, are either benefitting from or being harmed by settler colonialism, and that we can move forward with the reconciliatory action of seeking out and relying upon the perspectives of the people indigenous to the lands we occupy. Because, like Shirod Younker said, the relationship Native people have with their ancestral land means that they know things that we, as guests, don’t know about how to be human in this specific place.