What We’re Reading

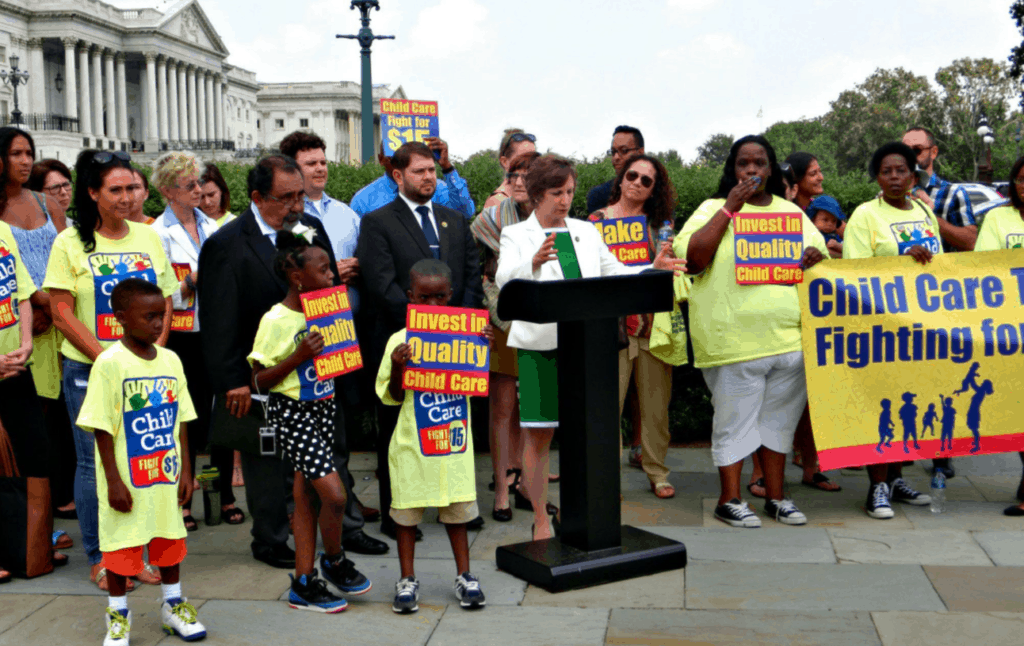

Congresswoman Suzanne Bonamici has issued a report on the state of child care in Oregon and across the nation. “Child Care in Crisis: Solutions to Support Working Families, Children and Educators,” is informed by conversations with providers, early childhood educators, and parents. Their stories illustrate in clear terms that healthy child care infrastructure is essential.

As our country grapples with systemic racism and ongoing gaps in access to opportunity, Bonamici’s report places child care issues squarely in that context:

“Fixing the child care system is also an issue of racial justice. The child care workforce is overwhelmingly women, and predominantly women of color. We must make sure child care providers and early childhood educators are paid a living wage that reflects the value of their highly-skilled work. Along with other barriers, families of color face income gaps that make quality child care even less affordable. Black, Indigenous, and other children of color are more likely to be in the least supported child care settings, and many child care settings are segregated by race. Resources must be distributed in a way that focuses on equity and on dismantling the systemic underinvestment in Black, Indigenous, and other families and workers of color.”

The report describes the pre-COVID child care crisis in Oregon, the ways the pandemic has exacerbated this crisis and created new problems, policy efforts to stabilize the industry during the pandemic, and a proposed path forward, including specific legislative actions to increase resources for families and the child care workforce.

An Existing Child Care Crisis in Oregon

Bonamici’s report says that the existing child care crisis in our state boils down to three main issues:

There is a vast, unmet need for high-quality, affordable child care.

“Early childhood education fosters children’s social and emotional development and prepares them to thrive in school and throughout life. Investment in early learning, including quality child care, is also good for the economy because it allows parents to work, seek work, or participate in their own educational advancement, while knowing their children are safe and learning. Unfortunately, there is more need than available care. According to the Oregon State University College of Public Health and Human Sciences, all 36 counties in Oregon were child care deserts for infants and toddlers before the pandemic, with only one child care slot for every three children who need care. Families in rural areas face even more scarcity. Access to affordable, high quality child care tends to be hardest for low-income families and families of color.”

Available child care comes at a high cost to families.

“Working families in Oregon pay some of the highest child care costs in the country. Child care can cost as much as, or more than, college. According to research by Child Care Aware, infant care in a center in Oregon averages $13,518 per year compared to $10,610 for in-state college tuition at a public college. In the Portland Metro area families are paying upwards of $21,000 per year for center-based infant care.”

“Although the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends that no more than 7 percent of household income go toward child care payments, the average in Oregon is 14.7 percent for preschool and 18 percent for infant and toddler care. This burden is much higher for low-income families.”

Compensation and benefits for early childhood educators are insufficient.

“The quality of a child care program depends on the quality of the staff. Increasingly, child care programs require advanced degrees and credentials to reflect the science and skills required of this workforce. Yet while education and training requirements have increased, wages have remained stagnant.”

“[Child care providers] are paid near-poverty wages, and nearly half are eligible for public assistance. In Oregon the average annual income of early childhood educators is $26,740, and nationwide they are paid on average $10.72 an hour. Additionally, child care providers and early childhood educators often lack some of the same benefits afforded to other workers, such as paid vacation time and health care. This disproportionately affects women and women of color, who make up about half of the child care workforce. Skilled, supported, and knowledgeable early childhood educators provide high-quality education, nurture the social and emotional development of children, and set children on a path to success. Low hourly wages and few or no benefits not only jeopardize the financial security of workers, but also negatively affect retention and quality.”

Problems Exacerbated by COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated all of the child care industry’s pre-existing problems. From the report:

“Prior to COVID-19, Oregon had 3,835 licensed providers with the capacity to serve approximately 128,000 children in child care. During the pandemic, Oregon Governor Kate Brown required that all child care programs close unless they were operating as emergency child care for essential workers—2,200 programs stayed open as emergency child care.”

“Although these providers have the capacity to serve about 23,000 children, only 15,000 children are currently enrolled. This means that only 12 percent of the children who attended care before COVID-19 are attending care during the pandemic. The providers that have remained open also face increased expenses to care for children safely, including the cost of purchasing personal protective equipment and cleaning supplies, and they also lose revenue because they must limit classroom sizes.”

As providers have responded to the pandemic by closing their doors, or by limiting enrollment to children of essential workers, many have struggled to pay for continuing operating expenses such as rent, insurance, and utilities with dramatically decreased or non-existent revenue. The report makes it clear that these circumstances will do devastating damage to an already delicate child care situation:

“The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) found that 27 percent of the Oregon child care providers it surveyed indicated they would not survive a closure of more than two weeks without additional funding. Alarmingly, 21 percent reported they could not survive a closure of any length without additional funding. Nationwide, we have already seen more than 330,000 child care providers and early childhood educators lose their jobs in a workforce that is predominantly women and women of color.”

“Without swift action, many providers and centers—whether they are small family childcare businesses, franchise locations, or national child care providers—will not be able to reopen their doors when physical distancing requirements are eased. The Center for American Progress estimates that as many as 44,000 slots could be permanently lost in Oregon.”

Policy Efforts to Stabilize the Industry During the Pandemic

Bonamici’s report outlines important legislative wins that have acted to bolster the child care industry and support families with young children during the pandemic. These include:

- The Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which expanded access to emergency paid sick time and paid family leave to nearly 87 million workers to help cover their own illness, illness of a family member, as well as child care and school closures

- The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, which included:

- Federal funds for the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) program for continued payment and assistance to child care providers and to support child care for essential workers

- Key supports for early childhood educators, including a suspension of payments on federally-held student loans

- Access to small business loans of up to $10 million that can be forgiven, if programs use the loans for specific purposes such as wages, paid sick or family leave, health insurance benefits, retirement benefits, mortgages or rent, or utilities

A Proposed Path Forward

Bonamici ends her report with a commitment to pursue additional legislation that would continue to stabilize and support the child care industry, as well as families with young children, through the pandemic and beyond. Details on the specific proposed and current legislation can be found in the full report.

“If substantial support is not provided to sustain the child care sector, programs will continue to bear a steep financial burden and be forced to shutter permanently. And if child care is not available as businesses reopen, parents—mostly mothers—will find it impossible to go back to work. This will have long-term consequences for our families and economy,” says Bonamici.