In Part II of this two-part story on mothers at Coffee Creek Correctional Facility in Wilsonville, Oregon, we learn more about the three mothers who participated in the Nurturing Healthy Attachments pilot program and are still participating in Head Start at Coffee Creek with their children.

Learn more about both programs as well as issues facing incarcerated parents in Part I of the story.

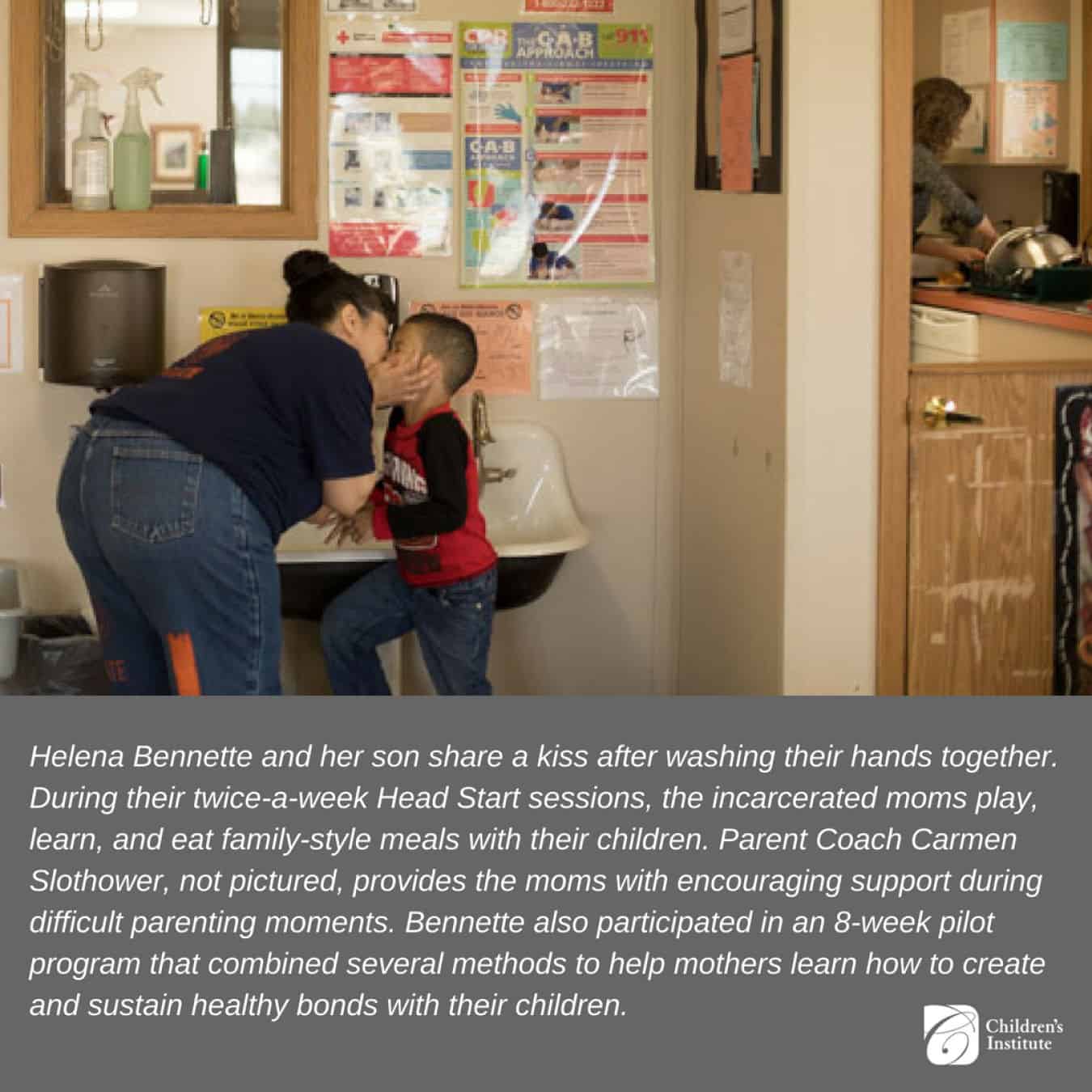

Helena

Helena Bennette is a 43-year-old mom of two. Her youngest son is 4, and her older son is 23. Incarceration broke up her time with both of her children.

“My oldest son was almost 5 when I was arrested (the first time), and I lost 10 years of his life. That bond was broken. I don’t want to say severed, but it was pretty broken and still is,” she says.

When she was arrested, her younger son was a little over a year old. She was immediately determined to participate in any parenting program the prison could offer.

One of her biggest lessons from Nurturing Healthy Attachments: It’s the parents who need training, not the children.

“Children are going to do what children are going to do,” she says, confidently. “But there’s, like, shark music.” The other two moms with her, Jessica Houser and Steffany Silsby, laugh knowingly. Bennette describes what “shark music” means: “Some people can handle a baby crying. Other people can’t. So, we say ‘shark music’ is what makes your anxiety start to rise,” she says, calling to mind the famously ominous two-note tune from “Jaws” that indicated imminent danger. “You learn to figure out, is this really a dangerous situation that you need to stop, or is this just making you uncomfortable?”

She says she used to think children were exhibiting “bad behaviors” that warranted punishment, but the program has changed that. “That was a big shift for me. The whole concept of punishment versus helping your child organize their feelings,” she says, adding that she learned the importance of “emotional regulation” in a way that has been beneficial for her whole family.

Bennette has been eager to share what she’s learned with her mom, who is taking care of her son, and her husband, who is also incarcerated. She recalls a time when she was on the phone with her mom and her mom told her son, “Don’t throw that at me!” Bennette saw an opportunity: “I said, ‘Don’t tell him what not to do—don’t tell him don’t! Tell him what you want him to do instead. Tell him to set it on the floor.’” Her mom tried it, and to her disbelief, it worked.

Bennette says her shift in perspective has been profound. “Now I know that when my child is playing or doing something on his own and he looks back at me, it’s because I’m his ‘secure base’ and it’s filling his cup. I used to think, what are you doing over there that you’re wanting to know where I’m at?”

“This experience has completely changed everything in my life,” she says.

Steffany

Steffany Silsby was pregnant when she was arrested for drug-related charges. She delivered her youngest child while incarcerated and was able to stay with her newborn for 24 hours before sending him home with his father. “He picked him up from the hospital and had never been around a baby,” she says. The 40-year-old mom has four other children, ages 20, 18, 17, and 14. Prior incarceration also interrupted her time with her older children.She says she didn’t know much about the program when she agreed to participate. “We just knew we might learn skills to help give our children healthy and secure attachments.” That’s all she needed to know. She had a lot of support from home: Her son’s father enrolled in online college courses, so he could be home with their child. He’s taken child development courses so that he knows how to be a great parent, too.

She had a lot of support from home: Her son’s father enrolled in online college courses, so he could be home with their child. He’s taken child development courses so that he knows how to be a great parent, too.

Silsby says one element of the program that really helped were videos from Circle of Security that demonstrated a mom’s exaggerated facial expressions as she tried to soothe a crying baby: “’Stop crying! Do you want this? Do you want this?’ From a baby’s perspective, that’s super overwhelming. So, we’ve learned to be where we’re not trying to change their emotions. They’re teaching us to acknowledge the emotion and label the feelings” rather than try to shut the feelings down, she says.

The videos used in Circle of Security help illustrate parenting challenges through different perspectives, which all the moms agreed helped them see parenting in a whole new light. And through the therapy-style setting, they explored their own beliefs, roles, and actions.

“We talked about why we were having a hard time doing that based on our own past and our own parents. And then learned how to let your children feel—it’s not about trying to make them stop crying, but to let them feel that it’s OK to cry. We try to figure out what the need is—sometimes my son just needs help organizing his feelings,” Silsby says.

“But we learned that 30 percent of the time you have to just get it right to have a secure attachment,” Silsby says. “I was like, Yes! I can get an F and still be a good parent!”

Steffany and Helena, who both have older children, say the program has also helped them repair relationships with older kids with whom they never had a secure attachment due to previous addiction and incarcerations.

“I was in a visit with my older son and I put my hand on him. I watched his cues to see if he flinched or pulled away—anything that would be a sign. And he didn’t. I felt really good. And then I said, I’m really touchy feely but I want to make sure that’s OK with you,” Silsby says. “He said, ‘that doesn’t bother me,’” she recalls. Silsby said she had never previously thought to check in with her kids about what level of physical affection they were comfortable with before going through the program.

She says another important thing she’s learned is the concept of “rupture and repair.” “I had a moment where my son was throwing rocks. We talk about being firm but kind—and not moving into mean. Well, when I get scared or mad, sometimes I move into a mean tone of voice. I’m working on finding my firm mom voice,” she says. But in the moment when her son was throwing rocks, her “mean mom” tone startled and upset him.

“I felt really defeated. I said to him, ‘I’m not mad at you. I love you when you’re ready to come back,’ and when he came back, I said, ‘I’m sorry that when I got mad, I yelled.’ He was like, ‘That’s OK, mommy!’ And then Carmen came and said, ‘there’s your rupture and repair!’ Those moments are super cool,” Silsby says.

Silsby’s son is also a biter—something she used to think was just bad behavior. “But I noticed that he chews on stuff as part of his emotional regulation. I thought, why don’t I find him something he can chew on?” When she gave him a special toy designed for chewing he was so excited that he asked to take it home with him so he could always have it.

Her son is getting ready for kindergarten in the fall. His dad scheduled visits to kindergartens in the area and Slothower volunteered to attend with him to help the first-time dad determine which school would be the best fit.

Silsby says her and her young son’s healthy bond is sustaining for her. “The type of bond that I have with my child now is so important. I don’t foresee being able to break that again. It’s just too important now,” she says.

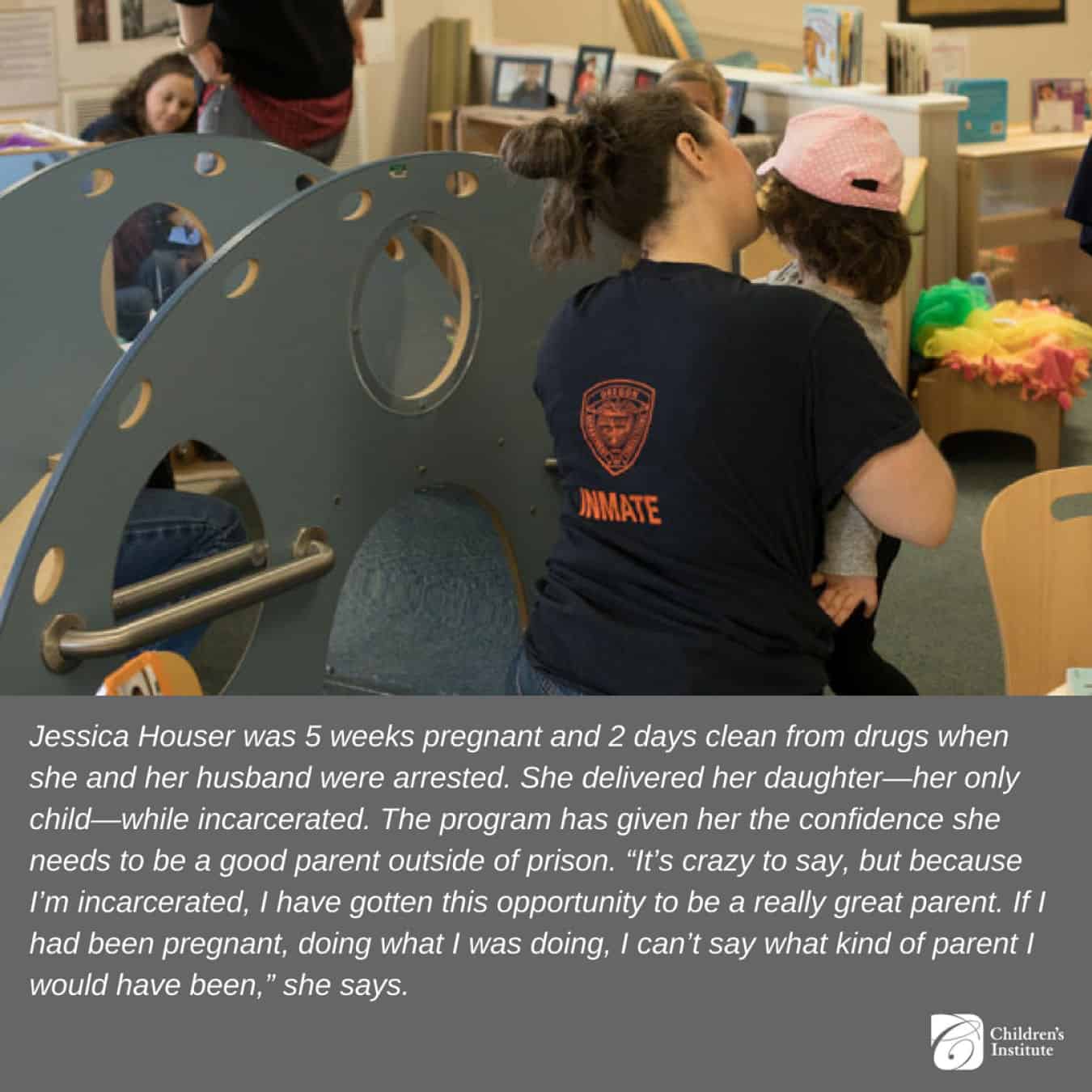

Jessica

Jessica Houser experienced two firsts at the same time: She had never been incarcerated and she had never been a mom. She delivered her daughter in prison and, since her husband was also incarcerated, she sent the newborn to live with a friend.

When she learned about the Nurturing Healthy Attachments, Houser was excited, even as she didn’t know all the details. She knew the program could help her connect more with her daughter and would involved studying videos of parent-child interactions, then analyzing them as a group. She signed up, eager to do anything while incarcerated to improve her parenting and ability to connect with her daughter.

Houser says before the pilot program, she used to scrutinize every interaction with her daughter: “How is she going to be as an adult if I do this when she’s two?” was something that would go through her mind after a negative interaction. It was stifling.

“It’s really reassuring to hear that. Just get it right 30 percent of the time—no one is perfect,” Houser says.

“It’s really reassuring to hear that. Just get it right 30 percent of the time—no one is perfect,” Houser says.

Houser has been sending her husband all the parenting information she can so he can learn, too. At one point, he asked Jessica about a visit he had with their daughter in which she repeatedly knocked over the tower they were building out of blocks: If I tell our daughter not to do something and she does it, he asked, is she being defiant? Jessica recalls telling him: “A tower is a pretty inviting thing for a kid to knock over. It’s not necessarily defiant.” Instead, she said, think of it as their daughter being playful and doing what toddlers do.

Houser says the pilot program has also helped her mom, who transports Houser’s daughter to and from Head Start while she and her husband are incarcerated. “My mom is really open to hearing how this works. And she’s noticing: My daughter has a need rather than my daughter is being ‘bad.’”

“I haven’t been a mom outside of prison. Having that constant coaching along the way has been so helpful. I don’t know what I would be like without this,” Houser says.

“It’s crazy to say, but because I’m incarcerated, I have gotten this opportunity to be a really great parent. If I had been pregnant, doing what I was doing, I can’t say what kind of parent I would have been,” she says. “Now I know I can be a good parent.” She said she’s noticed her bond with her daughter grow stronger gradually over the last year, when she participated in the pilot program.

To learn more about supports for incarcerated parents and programs around the country that are getting results, read our conversation with three national experts on the topic.