Teacher Erika Nelson meets with a student in the Skills Learning Center at John Wetten Elementary.

Rafael Otto contributed content and photos for this story.

At John Wetten Elementary in Gladstone, Oregon, a new classroom called the Skills Learning Center (SLC) offers students a calming environment for working on self-regulation skills. It features quiet music, soothing lighting, and a series of stations with calming activities like breathing exercises and fidgets.

Erika Nelson, a teacher at John Wetten with a mental health counseling background, works with students one-on-one to identify and regulate their emotions, learn how to use the space, and improve behaviors and habits.

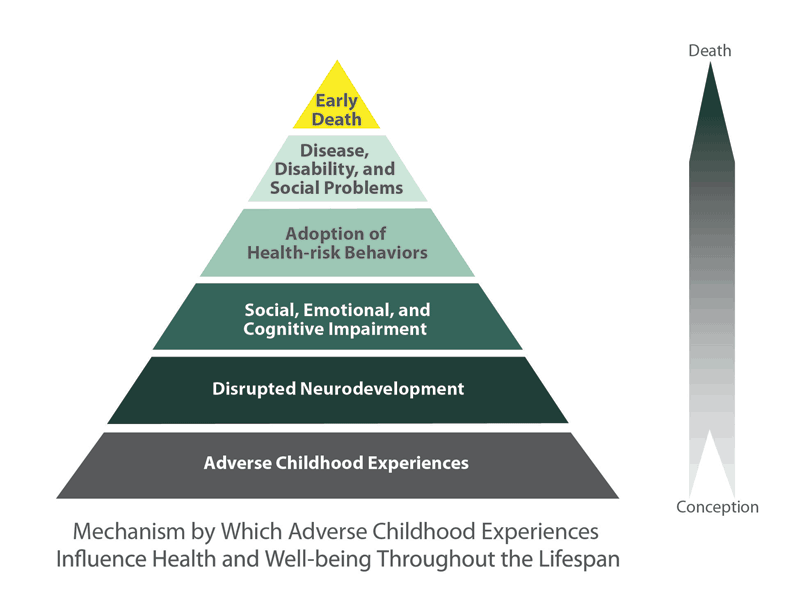

The SLC is just one aspect of a multi-year strategy in the Gladstone School District to address Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). ACEs fall into three categories: abuse, neglect, and family/household challenges. The ACE Study, conducted from 1995 to 1997 by Centers for Disease Control and Kaiser Permanente, involved more than 17,000 adult participants and found that childhood trauma can lead to a lifetime of negative health outcomes. The study also found that ACEs are common, with almost two-thirds of participants reporting at least one ACE and more than 20 percent reporting three or more ACEs. [Read More: A Brief Explanation of ACEs: Adverse Childhood Experiences]

When Gladstone Superintendent Bob Stewart first heard about ACEs, he wondered how a public K–12 school could satisfy rigorous academic requirements while working to mitigate childhood trauma. He had already spent time investigating causes for absenteeism in his schools and learned that many other factors such as poverty, mental illness, and domestic abuse, were affecting how kids learn.

Stewart brought his staff to a healthcare symposium featuring Dr. Vincent Felitti, a lead investigator on the ACE Study. There he realized the significance of understanding the long-term impact of childhood trauma. “We knew there were issues in kids’ lives that were limiting their ability to access education,” Stewart said, “but we didn’t understand the lifetime reach of it.”

The ACE Pyramid connects ACEs to development of risk factors over time.

Stewart and his team spent a year studying ACEs and how to address them in a K–12 setting, searching for schools or districts that might be leading the way. In 2012 Gladstone—along with six other districts across Oregon—received grant funding to form the ACEs Collaborative and Stewart set out to change how his schools addressed trauma.

Initially, Gladstone tried to focus on kids with a higher number of ACEs. But that proved difficult, because high ACE scores don’t always manifest with visible behavior issues. “Kids that have multiple ACEs in their life don’t necessarily exhibit bad behavior,” Stewart said. “The reality is, many people with high ACE scores can also be very high-achieving.”

Stewart also realized that helping a small number of children might not create a significant and lasting impact on his schools. “We realized that before we ever get to intervention strategies, we’ve got to look at what we need to do for kids that gives all kids the best chance to be successful at school,” Stewart said.

Stewart and his staff stepped back and reframed: Treat every child as if they had a high ACE score. “That became an ‘aha!’ moment for us,” he said.

Building a Culture of Care

At John Wetten Elementary, Wilson and her team focused on creating a school environment that was welcoming, safe, inclusive, predictable, and full of respect. She worked with a psychologist to help develop daily structure and made sure training extended to every staff member. Called the “Culture of Care,” the concept has extended to all four district schools: the Gladstone Center for Children & Families, John Wetten Elementary, Kraxberger Middle School, and Gladstone High School.

While the Culture of Care looks different in each school setting, the foundation is the same across the district. “The Culture of Care is built on relationships, it’s built on predictability, it’s built on safety,” Stewart said, because children who experience trauma at home tend to need those elements in their daily routine.

Principal Wendy Wilson from John Wetten Elementary says routines, relationships, and regulation are the cornerstones of the Culture of Care. “Routines help establish reliability, predictability, and the feeling of safety,” she said. Relationships help each student feel valued and know they are genuinely cared for. And regulation—learning about the fight or flight response, practicing strategies for settling down into their “learning brain”—helps students understand and talk about their emotions in a healthy, productive way.

A student works with fidgets and manipulatives in the Skills Learning Center at John Wetten Elementary.

At John Wetten, days begin with morning meetings where kids gather to exchange greetings and participate in activities that help them settle into the school day. “Whatever they came from at home, this sends the message that we’re in school and ready to learn,” Stewart said. During these meetings, kids as young as kindergarteners learn how to recognize and regulate their emotions so they can be successful in their school day.

The school has also added “calming corners” to their classrooms with fish tanks, dim lighting, soft music, and bean bag chairs to create a space and resource for children dealing with difficult emotions and behavior. Any student can go to a calming corner in their classroom at any time, but they cannot be sent there as a result of behavior issues. The calming corner is used as a resource rather than a punishment.

John Wetten expanded the Culture of Care by adding the Skills Learning Center in the fall of 2018, an additional layer of support for kids who are displaying behavior issues in class.

When a teacher refers a student who might need help, Vice Principal Buchanan, SLC teacher Erika Nelson and a team of teachers work to better understand reasons for the child’s behavior, history of behavior issues, and any additional context. Some of the students referred to the SLC have caused “room clears”—meaning their behavior (throwing desks, tearing things off the wall) necessitated clearing the other students out of the room for safety. Many of the students had numerous disciplinary interventions last year due to their dysregulated behavior.

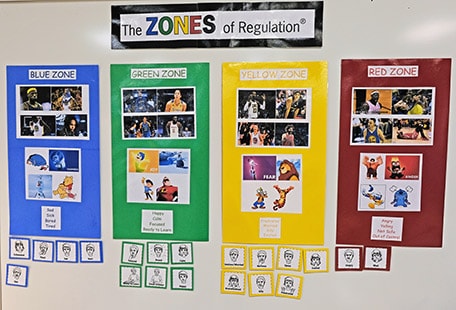

The Zones of Regulation help students identify emotions when they arrive at the Skills Learning Center.

Once a student is referred to Nelson, she schedules 20-minute sessions each day to orient them to the routine and tools. The students engage in a routine that consists of a sensory path (jumping, wall push-ups, hopping, etc.) and then one regulating station that has specific calming tools such as a light table, dark space, fidgets, fish tank, sand, or rice. They end their routine with yoga, breathing exercises, and a brief Zones of Regulation lesson at the learning table.

Students learn about the Zones of Regulation with Nelson, a tool and curriculum that locates their emotional state in one of four zones: Blue, Green, Yellow, or Red. After spending time in the SLC, the goal is to return to the Green Zone where students should feel happy, calm, focused, and ready to learn.

Assessing Results

Two months after the SLC opened, Nelson said they are seeing results. None of the 18 students who were using it had caused a room clear and the number of disciplinary referrals had dropped. Students also reported sharing their learning about the Zones of Regulation and tools they were using with their parents.

Gladstone’s Culture of Care has also reduced behavior problems, improved attendance, and improved test scores in both English Language Arts and math.

As Stewart and his team continue to improve their approach to addressing trauma and understanding ACEs, they’ve met with district leaders from around the state to share what they have learned. All the district representatives involved in the initial cohort of districts from 2012 have said the focus on ACEs has been a “game changer” for their schools.

A student wraps up his time in the Skills Learning Center and prepares to return to his classroom.

“It’s difficult to make system changes,” Stewart said, “and very few school districts do it. But every one of the seven districts have said this work leads to real systemic changes.”

Stewart believes that understanding ACEs and working to address it through an approach like the Culture of Care could be transformative for many more schools. He is working to develop a set of best practices and, eventually, wants to build a model that can be scaled to schools across Oregon and the country.

Additional Resources

A Brief Explanation of ACEs: Adverse Childhood Experiences

Superintendent’s State Crusade to Help Schools Help Students of Trauma

The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study: How are the findings being applied in Oregon?