To design or strengthen a high-quality early learning system, we need a team that is diverse in perspectives and skill sets and has high levels of trust in each other. Developing this type of team happens over time, with intentional routines, in the process of doing the work. A first step is to recruit members of your early learning team, considering the following roles:

-

-

- Community members

- Culturally specific organizations

- Family members

- School board members

- Early learning educators within and beyond the district (licensed and classified)

- Early Intervention/Early Childhood Special Education providers

- K-2 educators (licensed and classified)

- English language development, Title I, and special education staff

- Elementary principal

- District staff (early learning, teaching and learning, elementary and/or special services)

- Instructional coaches and/or teachers on special assignment

-

Once the team is gathered, we recommend addressing team members’ hopes and fears and using those to develop team norms. If members of the team already know each other or have worked together before, it might be tempting to skip this step. We encourage your team to review hopes and fears and create norms no matter your level of familiarity. As a new team with a new purpose, this is your best opportunity to lay the foundation for a productive group with healthy communication.

Positionality

The social and political context that creates personal identity and shapes access to power due to race, gender, socioeconomic status, professional role, and other factors

Activity: Hopes & Fears + Norm Setting

Time: 30 minutes

Materials:

- In Person: whiteboard or chart paper, markers

- Digital: Mural, Google Jamboard, or Microsoft Teams whiteboard

People: Experienced facilitator and Early Learning team members

Purpose: Name aspirations for this work and name concerns about achieving those aspirations. Come to consensus about how you and your teammates will work together to maximize your hopes and minimize your fears.

Process:

4 min: Ask participants to write down their greatest fear for this team experience: “If this is the worst experience you’ve had, what will have happened (or not happened)?” Then they write their greatest hope: “If this is the best team experience you’ve ever participated in, what will be its outcome(s)”?

10 min: Participants call out fears and hopes as the facilitator lists them on separate pieces of chart paper. List all fears and hopes exactly as expressed, without editing, comment, or judgment. Encourage folks to be concise when they share their hope or fear—keep it to 1 line for the chart paper and 2 sentences for explanation because we want to have time to hear from everyone. No need for you to respond to each one, except to say, “thank you,” and solicit ideas from other people.

1 min: Transition to norms by explaining: “In order to maximize our hopes and minimize our fears, what norms will we need?” Explain that norms are guidelines for interaction/meeting, and can include both process (like start and end on time) and content (like taking risks with our questions and ideas).

2 min: What are norms? Why do we need them? What purpose do they support?

-

- Norms are how the purpose gets “lived” in the team

- Specific behaviors that the team agrees to and commits to uphold in order to achieve real team and real work

- Build trust, clarify group expectations of one another, and establish points of “reflection” to see how the group is doing regarding process

- Supports team to achieve hopes and minimize fears

Review example of team norms (have these written on board)

-

- Take an inquiry stance: speak up, raise questions

- Ground statements in evidence

- Assume positive intentions: argue the idea, not the person

- Stick to protocol and agenda

- Start and end on time

- Be engaged: use devices to support the work, not to distract from it

10 min: Brainstorm this team’s norms: “How” will we work together to achieve our purpose and goals?

Think time:

-

- What do I personally need to work well on a team?

- Which norms of the example teams to I want to adapt?

- Share out and chart:

-

- Personal needs and those to adapt from examples

Step back and consider:

-

- What’s missing? Are these all behaviors we can monitor?

- Do we need any additional norms, specific to our team to achieve our mission and purpose?

3 min: How will we hold ourselves accountable?

-

- What routines do we need in place to ensure we all understand the norms?

- How will the team make the norms live?

- What happens when the norms are broken?

Notes & Tips:

If you are feeling pressed for time, you can choose to not write hopes and fears out on chart paper.

Hopes & Fears activity adapted by Northwest Regional ESD’s 9th Grade Success Network from DataWise at HGSE.

Understanding how our Identities Shape our Perspective on a Team

We think about social identities as the groups to which we belong. These groups may be shaped by race, ethnicity, nationality, language, gender, sexual orientation, age, geography, ability, religion, class, or another affiliation. They’re also shaped by our communities, families, careers, interests, and talents. Social identities are both overlapping and fluid – we belong to many groups and our identities related to these groups are always changing.

Understanding our social identities helps us to figure out our positionality*. It helps us to know who we are in relation to each other. Most importantly, it helps us to know which perspectives we’re bringing to our team and helps us to uncover which perspectives we may be missing.

When we build an inclusive team it is important to name the power that we have on the team due to our positionality. The team will be more likely to share decision-making and prevent tokenizing the voices of community members, families, and/or students who historically do not have as much power in the system. When we own our own power, which is often unearned, we can work to relinquish it to create more equitable teams.

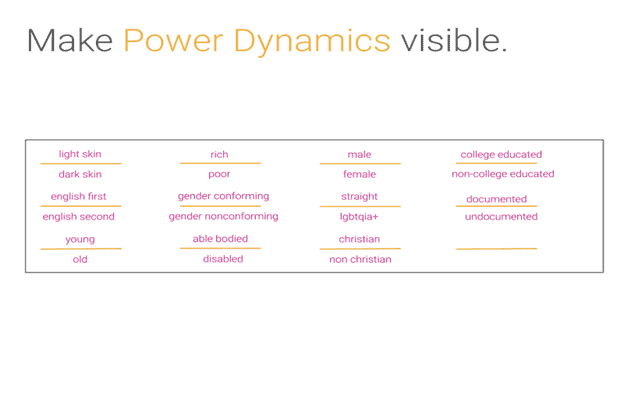

The graphic below provided by Equity Meets Design shows 11 ways that power might show up on teams. The assumption is that in our culture, the characteristic on the top is given more power in most spaces. Spend time noticing and owning what other positionalities might be on your team that bring a power differential, such as role in the organization, years of experience, or team facilitator.

Activity: Explore Social Identities

Time: 30-45 minutes

Materials:

- In Person: single sheets of 8.5×11 or larger paper per person

- Digital: Mural, Google Jamboard, or Microsoft Teams whiteboard

People: members of the Early Learning team

Purpose: This activity is used for individual and group exploration of social identities, privileges, and belief systems. It is intended to help members of the early learning team better understand how their identities and perspectives shape the systems they design for young learners, and to reflect on if the team adequately represents the social identities of the children and families for whom they are designing.

Process:

10 min: Each team member draws a molecule diagram with 6-7 circles around a central circle. The person writes their name in the center circle. In each additional circle, the person writes words that describe parts of their identity – words that describe who the person is and how they interact in the world. For example, one circle might contain the word “Indigenous” and another might be “midwestern.” As an additional step, participants can add a layer of circles with words others use to identify them.

10 min: Partners or triads share their circles with each other, giving each participant equal time to share, uninterrupted.

10 min: Whole-group debrief. The facilitator asks:

- With which descriptors do you identify most strongly? Why?

- With which do others identify you most strongly? How does that feel?

- Have any of the elements of your identity worked to your advantage? Disadvantage?

- How do my identities hold power and privilege?

Notes & Tips:

Social identities can be sensitive or painful topics for people from non-dominant backgrounds. We strongly recommend using your team’s norms for this activity.

The facilitator may start the activity by sharing their molecule and talking through their various social identities.

Credit to: National School Reform Faculty

Organizing Your Team on the Problem of Practice

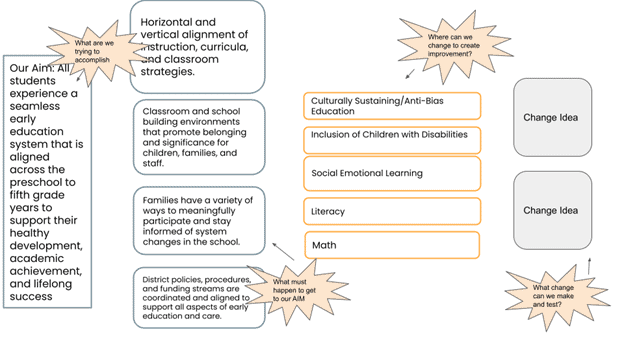

A theory of improvement is essentially a hypothesis about the conditions and changes needed to achieve an aim. Children’s Institute has worked with a diverse set of districts to build and start testing a theory of improvement to help school districts get started on their early learning alignment goals. The figure above is a visual representation of this theory.

A theory of improvement is not intended to be an exhaustive list of everything you might do to meet your goals, nor is it a comprehensive to-do list. Its purpose is to help you:

-

- Prioritize among the many possible strategies for accomplishing your goals

- Organize the different parts of a system to ensure that system change is effective and sustainable

- Organize the efforts of different parts of your team working on this goal

- Select the best ways to measure toward your goals

- Capture what is occurring by revisiting and revising your theory

To use this theory of change with your team, start by identifying your strengths in the secondary drivers, or the specific aspects that your systems need to design or improve in order to meet your aim. Have all team members reflect on evidence of strengths. From there, have your team members discuss opportunities for improvement. It is important to remember that “Every system is perfectly designed to get the outcome it gets” and keep the discussion focused on the system and not on individuals or groups of individuals. Listing growth opportunities can be overwhelming, so be sure to elevate a starting position once you’re done.

Some suggestions for prioritizing a starting place are to identify:

-

- Where does this team have access?

- Where is there improvement work already happening?

- Where are there currently resources?

- Where is the will of the team?

Be Problem-Specific

Once you have prioritized a starting place it is helpful to name the problem your team seeks to solve related to your prioritized starting place. A problem means an issue or outcome that is negative – something that you want to improve. A good problem statement is critical to guide and focus the work as well as to create a shared understanding of what we hope to improve. There is not a single path to developing a problem statement. Some teams may identify a problem quickly and early and move on to a root cause analysis. Other teams may need to spend more time investigating local data and research before identifying a specific problem.

Being problem-specific helps teams avoid three key improvement missteps:

-

- “Solutionitis”: Solutionitis occurs when solutions are named with little input from the children, families, and communities experiencing the problem. This practice often leads to solutions that are misaligned with community needs, resulting in damaged community trust and resources wasted on a solution that does not match needs.

- Blame: Blaming people or community behavior and not the environments that enabled those behaviors to happen

- Believing the barriers: There are so many perceived structures and rules that stand in the way of improvement. When we believe that all obstacles are immobile, improvement is limited from the beginning.

When your team is drafting various problems, ask the following questions:

-

- Is the problem blame-free?

- Is the problem solution-free?

- Who is experiencing this problem?

- Is the problem a reasonable size and level of complexity for our team to tackle?

Some examples of problem statements in our work are:

-

- Students do not have opportunities to apply mathematical learning in an authentic and meaningful way.

- Young students’ mental and behavioral needs are not being addressed in school.

- Our system is not designed to fully include our children with disabilities in all early learning classrooms.

- Our system is not designed to provide culturally sustaining, anti-bias early learning instruction.

Adjusting Your Team

Teams must examine their own role in the current system and how they might be part of the power structures that perpetuate the status quo. We must ensure that we have included diverse perspectives from the community who have had different experiences in the system on our team. We know which perspectives are included on our team, and when we think about the problem of practice we will be working on, it is important to acknowledge which perspectives we’re missing.

Examples:

Problem: Families don’t feel welcome at school.

Perspectives: Family perspectives are needed, mostly from families who are not feeling welcome.

———

Problem: The preschool teacher does not feel part of a teaching team.

Perspectives: Preschool and early elementary teacher perspectives are needed; they should be part of the problem-solving.

To adjust or expand the team, we encourage you to invite and center those marginalized by the system, instead of planning for the “average” child or “average” educator. Those who are being disenfranchised or ignored have important perspectives and insights for designing solutions. If we center those marginalized by the system, everyone benefits.

As we learn more about our system and notice that perspectives are missing, we may need to add new members to the problem-solving team. When this is challenging due to time or resource constraints, we need to find creative ways for people to participate, using technology, translation, transportation, food, and child care to support inclusion. We need to remove barriers to participation.

Not every social identity may be represented on this problem-solving team. What is important is that the team acknowledges the existing positionality, and finds ways to bring in perspectives that are missing.

Additional Resources

Stages of Team Development © Elena Aguilar, The Art of Coaching Teams: Building Resilient Communities that Transform Schools. Jossey-Bass, 2016.

Tips for Inclusion

-

- Expect discomfort. New members will have different ways of thinking about a problem, describing it, different solutions, and even different ways of just participating in a group.

- Be adaptable. Multiple perspectives may take you off your agenda to attend to issues that others feel may need to be addressed first.

- Plan for uncommon meeting times based on family schedules.

- Speak First, Speak Last: Give the first and last opportunity to speak to the people who are typically least represented.

- Think through how time, technology, transportation, food, and child care can support an inclusive team.